Why do certain words and expressions sound so good in German? Take the title of this show. Its English translation (A Vague Feeling of Unease) is not bad, but the version in Wagner’s language sounds much more expressive. And fitting: though Thomas Helbig is the only German, the practice of the three artists is drenched in a somehow classically German atmosphere of Angst and das Unheimliche.

Helmut Stallaerts’s art, for example, is characterised by oppressiveness and unease. Though the thirty-year-old Belgian also makes scale models, videos and photographs, he’s best known for his paintings of uncanny, somehow archaic scenes often stretching the medium’s boundaries by being painted on the most diverse supports. Puzzle (2009–10), painted on a jigsaw whose pieces are slotted together forcibly, depicts a group of sinister-looking men in uniform, their leader seemingly in the middle. On closer inspection, the latter has a funnel on his head, like a dunce’s cap. It says a lot about the way Stallaerts deals with power, namely the blind faith some people display towards figures of authority. Most of the time he renders notions of power in a subdued way, as in The Opportunist (2011), in whose empty corporate office one discerns the vague outlines of a character with a bowed head. The work is rendered in the artist’s characteristic sallow colours, contributing to the atmosphere of unease.

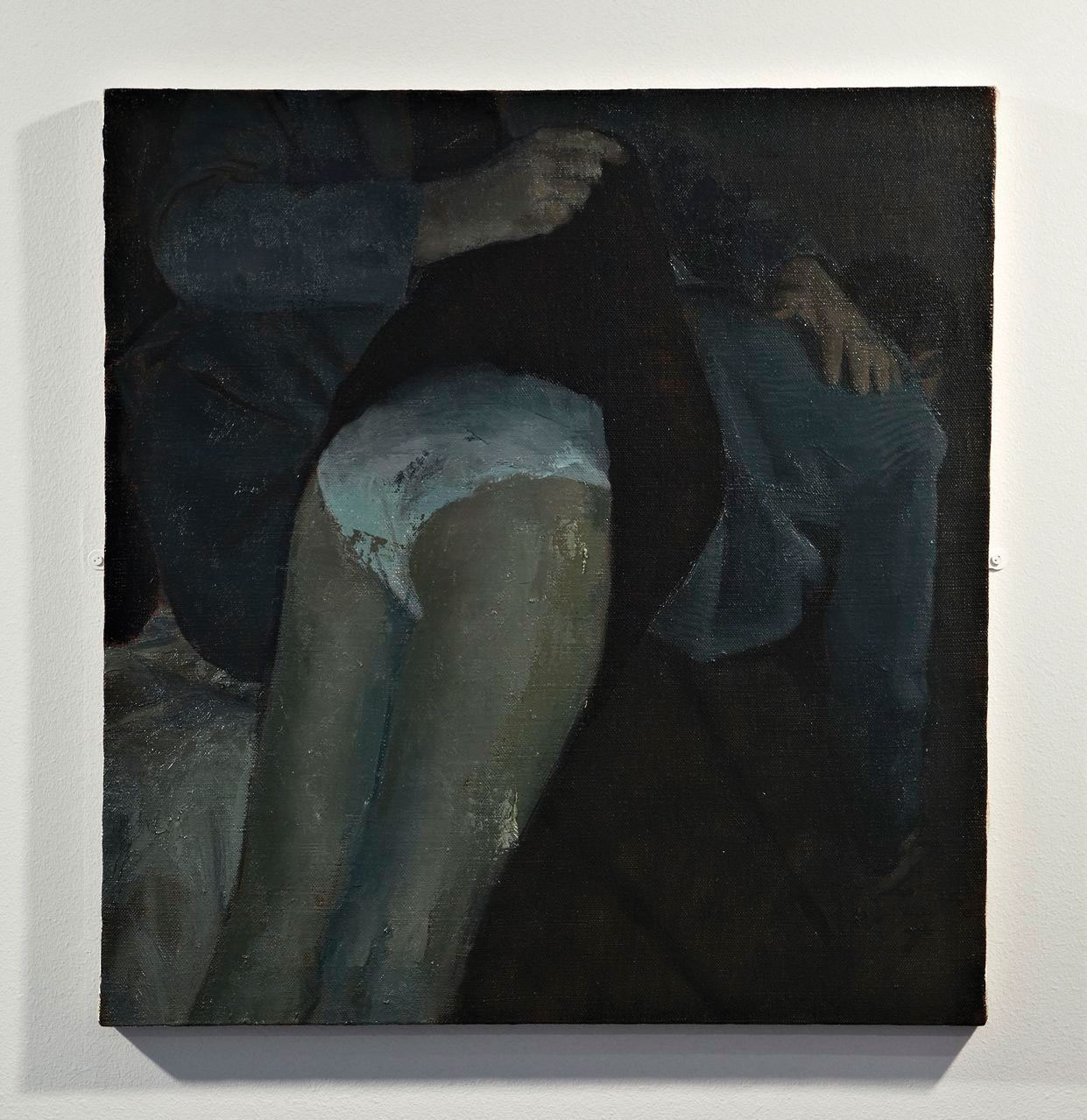

Victor Man’s palette is darker, with green/ blue hues and some of his paintings so black you can hardly see what they represent. Grand Practice (2009), depicting a man dressed as a horse, is set in near-darkness, creating an uncanny, dreamlike feeling that echoes the burlesque masquerade often recurring in Stallaerts’s work. The unease is more explicit in Untitled (From, If Mind Were All There Was) (2009), which portrays a woman being spanked. The perpetrator is cut out of the composition; attention is completely focused on the violent act.

Thomas Helbig’s tall sculptures, aptly placed next to Stallaerts’s scale model of an inverted tower carved out of bone, also exude violence. Though the sculptures have a classic base, they start formally, disintegrating towards the top where one can vaguely recognise elements – like a sleeve or a button – of a traditional bust. Helbig is of course also known for his paintings; these have monochrome backgrounds with stains and spots, which the artist physically accentuates by adding strings of paint that he pushes through a syringe. It results in abstract expressionist-like, existentialist works that emphasise the medium’s materiality. The support almost becomes a body of flesh and blood. That is also the case in the work of Stallaerts and Man: Stallaerts’s Josefine (2010) depicts a weightlifter painted on a human skull, while Man’s Ubiquitous You (2008), a portrait of a headless, handless doll, is mounted on a pelt.

Medium or style notwithstanding, the works here share a mood of disquiet expressed not only through the subject matter or colour range but also through the way the artists stretch and misemploy their medium. Including Helbig’s work was a clever move, its more abstract character allowing for a moment of rest. In doing so, the curators prevent the show from collapsing under its own weight: a considerable risk for exhibitions with such a loaded theme.

This article was first published in the April 2013 issue.