At the same time as Richard Hamilton’s iconic collages have taken over Tate Modern, and Hannah Höch’s retrospective at the Whitechapel has gathered a massive body of work demonstrating a similar assemblage technique, a different collage show is tucked away at a tiny space on East London’s busy Hackney Road.

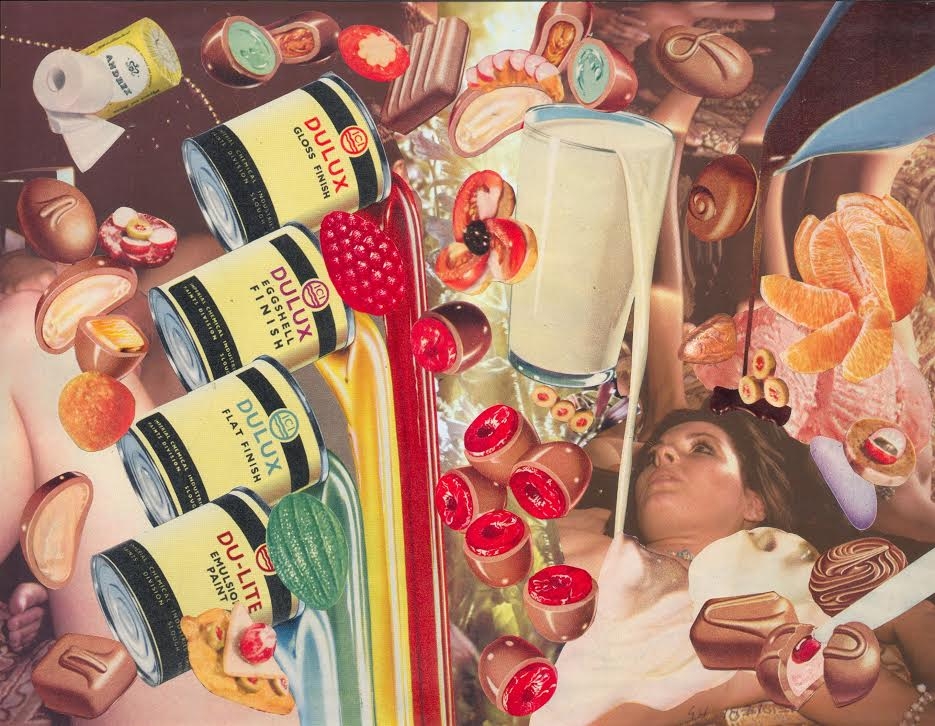

Robert Holcombe (1923-2003) was a Slade contemporary of Hamilton, studying printmaking at the school between 1948-1951; however, collage was his obsession. In his small, highly aesthetical works, anatomical drawings, body parts, multiple moons and colourful textiles are superimposed on architectural environments, creating a surreal, uncanny atmosphere.

In one of his many letters to Eduardo Paolozzi, a founding member of the Independent Group, which Holcombe took a marginal part in, he writes: ‘I use only found materials on which I leave no obvious mark and I reconfigure them under an identity that is not mine.’ Not surprisingly Holcombe is a fictive artist.

He and his works are the creation of Wayne Burrows, a writer, artist and poet based in Nottingham. Holcombe was born as a minor figure in one of Burrows’ novels, but soon took over the book. Many visual artists have used parafictional identities – from Marcel Duchamp to contemporary artists such as Roee Rosen, Michael Blum, Eva & Franco Mattes and Iris Häussler. But what is the significance of this deception? Holcombe is not a hoax; it is mentioned that he is fictive in the press release. Burrows says that people want to believe in something that ought to have happened – and Holcombe ought to have happened.

A fictive persona works best when well grounded in reality. Holcombe was influenced by the surreal anatomical sculptures of the Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow, who he apparently met in Paris in 1963, and to whom he dedicated The Krakow series (1964). From 1955 until his retirement in 1988 he worked in the Leeds City Planning Offices, which explains his interest in architecture and interior design.

The Modernist series (1965-1976) addresses areas more closely associated with pop culture, such as design, fashion and film. The Family Bible Series (1967), too delicate to be exhibited and therefore projected, relates to Holcombe’s Methodist upbringing. He is distorting scenes from the Old and New Testaments, like Moses descending from the Mount bearing not the Ten Commandments, but two brightly coloured Cream Sodas.

Particularly interesting is the series Performing the Curtain Ritual I – IX (1966); nine small collages in which African characters are positioned within western modern domestic interiors. It seems like a male version of Höch’s The Ethnographic Museum series.

Holcombe’s works infuse the leftovers of mid-twentieth-century western pop art with elements of a surreal dark side and a healthy dose of a far more cynical humour than the ‘original version’ of it. This show is just a small fragment of a larger body of work, and as many gaps exist in the archive of Robert Holcombe, held by his sister ‘Elizabeth Booth’, we have much more to look forward to.

March 2014