Sadie Benning’s debut at the 1993 Whitney Biennial, a smoky DIY video shot with a toy black-and-white camera, announced her as a precociously talented teenager with a sophisticated understanding of film and a stake in the gender politics of the era. Filmed in her childhood bedroom, the work interspersed snippets from a 1950s psychodrama about a homicidal schoolgirl, hand-lettered signs and confessional explorations of her queer identity. Less an effort to parse the media’s formulaic presentation of the sexual and the feminine – although it was a major and early sally in that genre – the piece reclaimed clichéd content by infusing it with the personal and the handmade. It still bites: the video is included, fortuitously, in the New Museum’s time capsule survey of New York, NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, concurrent with Benning’s one person show.

In her recent work, Benning employs similar formal techniques to comment on life in a nation plagued by shabbiness and institutionalised militarism. War Credits (2007–13), a black-and-white video in which the credits from three Hollywood films are reduced to abraded bursts of light and lines of illegible text, suggests America’s continuing engagement in the buck-stops-nowhere campaigns abroad. In Parts (2012) combines seemingly unrelated outtakes from personal videos: a pacing leopard, the desert seen through the windshield of a moving car, a 45rpm disc spinning on a turntable, wheat in a derelict urban lot, a wall clock. Ghostly whorls burned onto the camera’s tubes by overexposure to light float over the images. Things move but never really get anywhere. The scenes are as vitiated of meaning as the lines in War Credits, the former perhaps the wages of the latter’s sins.

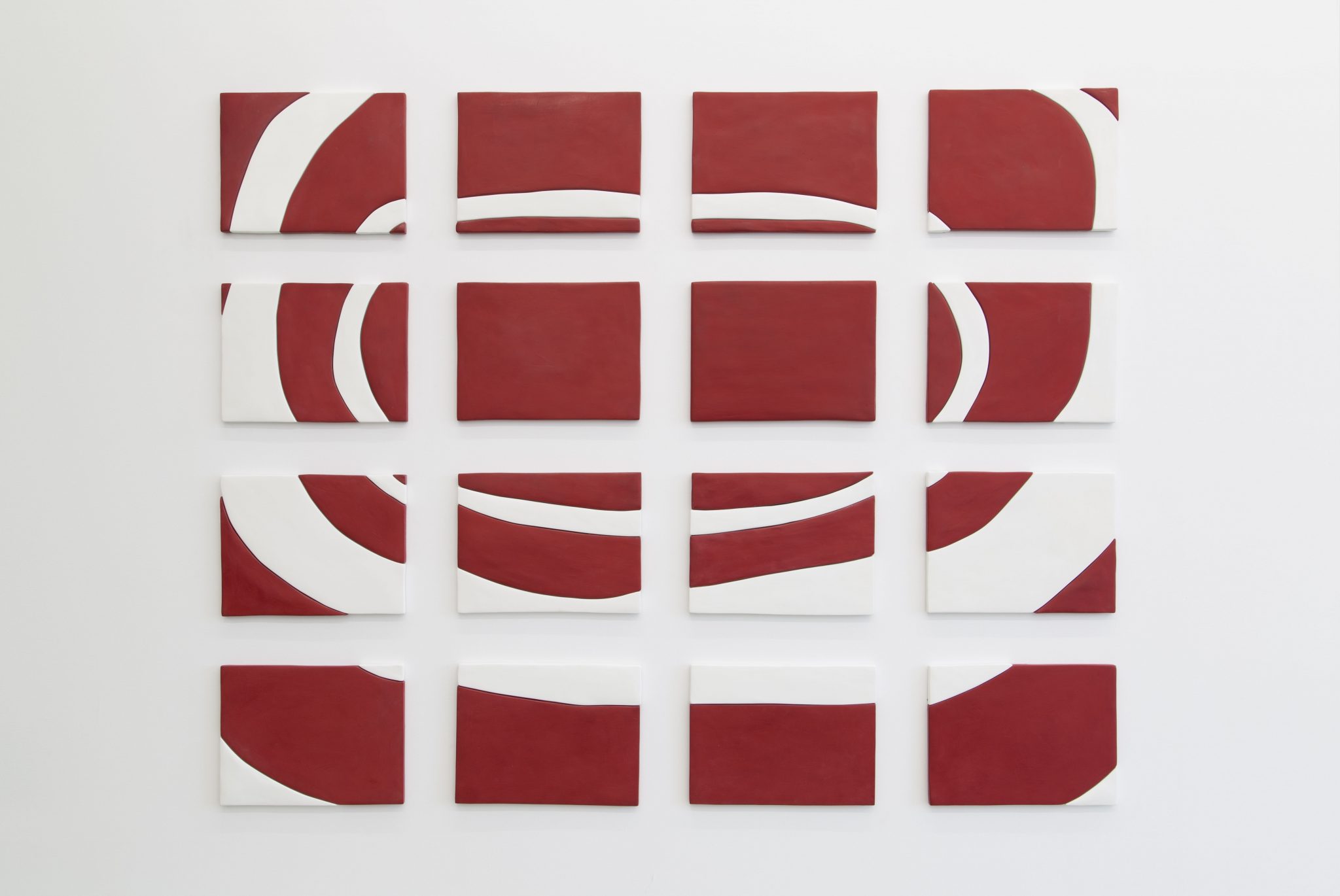

Dissolution and inscrutability appear to be the point: the show also includes two wall reliefs based on generic 1960s abstract paintings, a series of graduated right angles in alternating white and blue, and concentric red and white ovals cut into rectangles and separated to form a grid on the wall. Following the trajectory of those arcs, however, reveals that their curves do not align. The mismatch induces a vague anxiety and pushes the eye to the empty spaces between the panels. The emphasis is on the time and space in which viewers experience the work. As in an existentialist novel, that’s where our purpose lies.

The playfully sharp irreverence of Benning’s breakout work has matured into a poetic sense of remove, a melancholy sense of time and of individual inconsequence. The shift jibes with the disquiet her work suggests. But the viewer wants more, and given the anomie that haunts this show, perhaps Benning does too.

This article was first published in the Summer 2013 issue