Clare Kenny, the artist who curated this exhibition, took its title from John Szarkowski’s text The Photographer’s Eye (1966). ‘Time’ is one of five issues that Szarkowski found key to understanding photography, the others being ‘The Thing Itself ’, ‘The Frame’, ‘The Detail’ and ‘The Vantage Point’. Kenny has already mounted shows around the first two of these last four terms: The Frame was made up of her own work, very large pieces on exposed photographic paper to make generously curling forms in abstract colour that elbow their way into the sculptural realm. In Time, however, photography is scarcely to be found. Nonetheless, works by Manon Bellet, Martin Chramosta, Gabi Deutsch, Sonia Kacem, Sam Porritt and Gitte Schäfer play dare with the very questions of immediacy and authorship that delayed photography’s acceptance into the art canon – to quote Szarkowski, ‘Paintings were made… but photographs, as the man on the street put it, were taken’.

Bellet’s modest cyanotypes come closest to the familiar photographic tradition, though the power of other artists’ statements overshadows the delicacy of hers. Chramosta’s canvases are not much larger, but laden with history; Plenair à la Bohémienne (Le Jardin à Czaslav) (Bohemian Outdoors (The Garden in Czaslav), 2010/12) owes its dappling to the weather it endured when mounted on an easel in the titular garden for more than a year; other canvases in the exhibition accrued patinas over decades stored in an attic while in the possession of Miloš Saxl, an artist prosecuted for his oppositional style in what was then Czechoslovakia. Chramosta has not projected onto his canvases, but enables them to gather their own shadowy images. Meanwhile Kacem’s Holy Crap (2013) – a glorious swirl of marble powder, cement, fringing and other shredded detritus on the floor – elevates base materials to update the painter’s form of still life, or ‘dead nature’, as the French call it. Man goes from dust to dust, and Kacem captures this with aplomb.

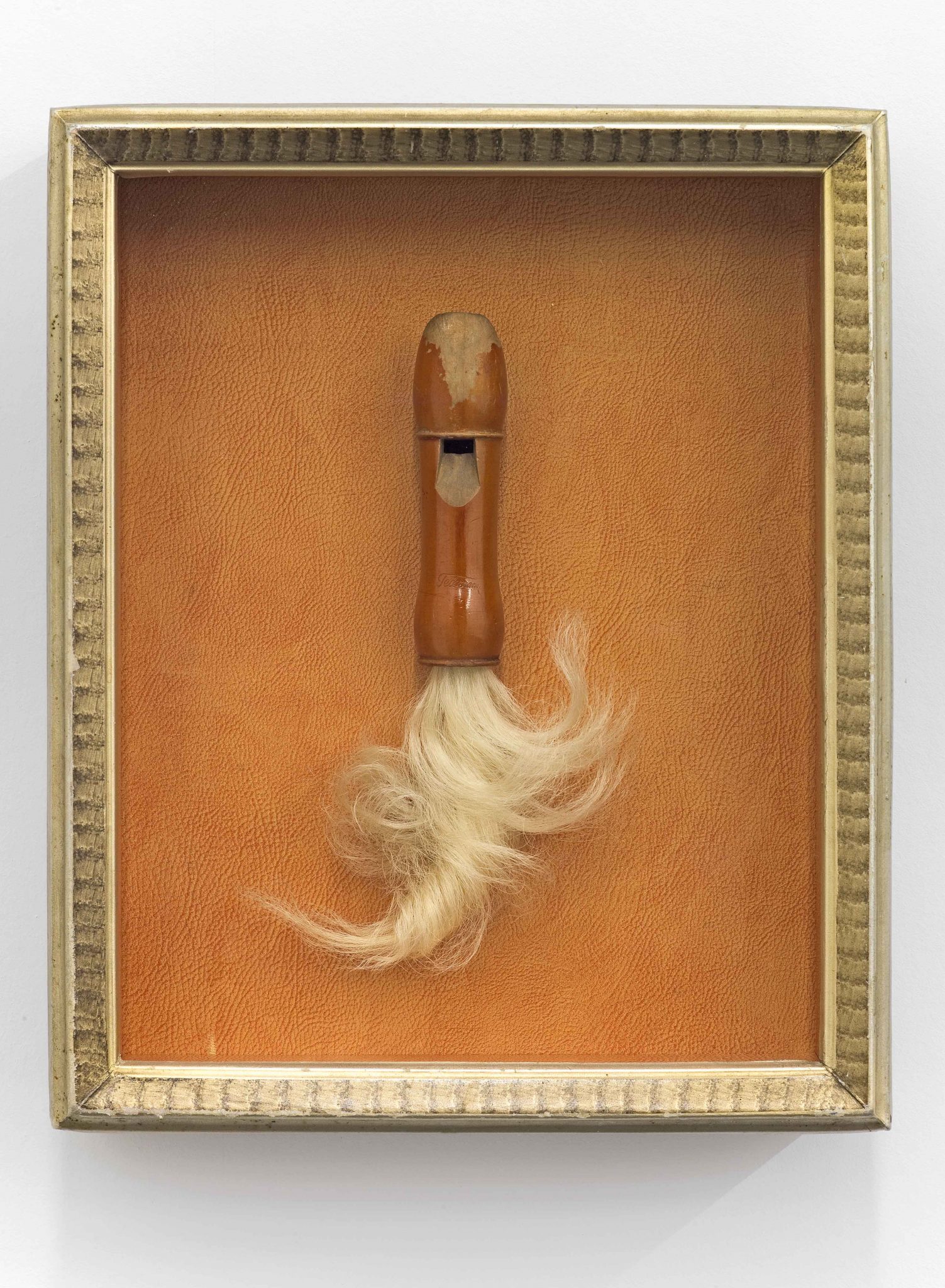

Porritt’s ink-on-paper triptych Going East (2010) translates time into diagrammatic form; he draws spirelike upward protuberances that indicate travel as they morph from Western Christian outlines to Orthodox or Islamic bulbosity, while the tightly packed looping lines that fill them convey density. Schäfer’s framed reliefs composed from flea-market finds follow the surrealist sculptural tradition of Meret Oppenheim; Zwergenstrauch (Dwarves’ Bush, 2011) is made of lichen packed behind glass, a miniature garden in a material that could have been designed to connote graceful decay, given its ever-faded hue. In another, Melodus (2012), a lock of grey hair embodies the breath, and life, coming from a recorder mouthpiece.

Szarkowski views photography as a medium that had emerged ex nihilo, in comparison to the leisurely development of painting. Photographers have had not only to learn what the medium could do, but also to comprehend the complexities specific to it before photography could be deemed successful. When it comes to time, photography can split the second with great visual effect. By selecting these works in response to Szarkowski’s text, Kenny suggests that duration is better expressed in other media, particularly when they borrow from history to capture momentary pauses that are resonant, but transient.

This article was first published in the April 2013 issue.