It was, perhaps ironically, William E. Jones’s spell working for porn king Larry Flynt that left the artist with such a nuanced approach to editing found film and video footage. Indeed it was the process of editing bargain porno DVDs from nearly 30 years worth of films in Flynt’s back catalogue that afforded Jones an opportunity to witness the changes that technology and economics wrought on the medium. These he has highlighted previously in the films The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998), which identified an influx of new bodies to the industry, and All Male Mashup (2006), in which only peripheral elements such as landscape and dialogue are shown, stripping the material of the sexual act.

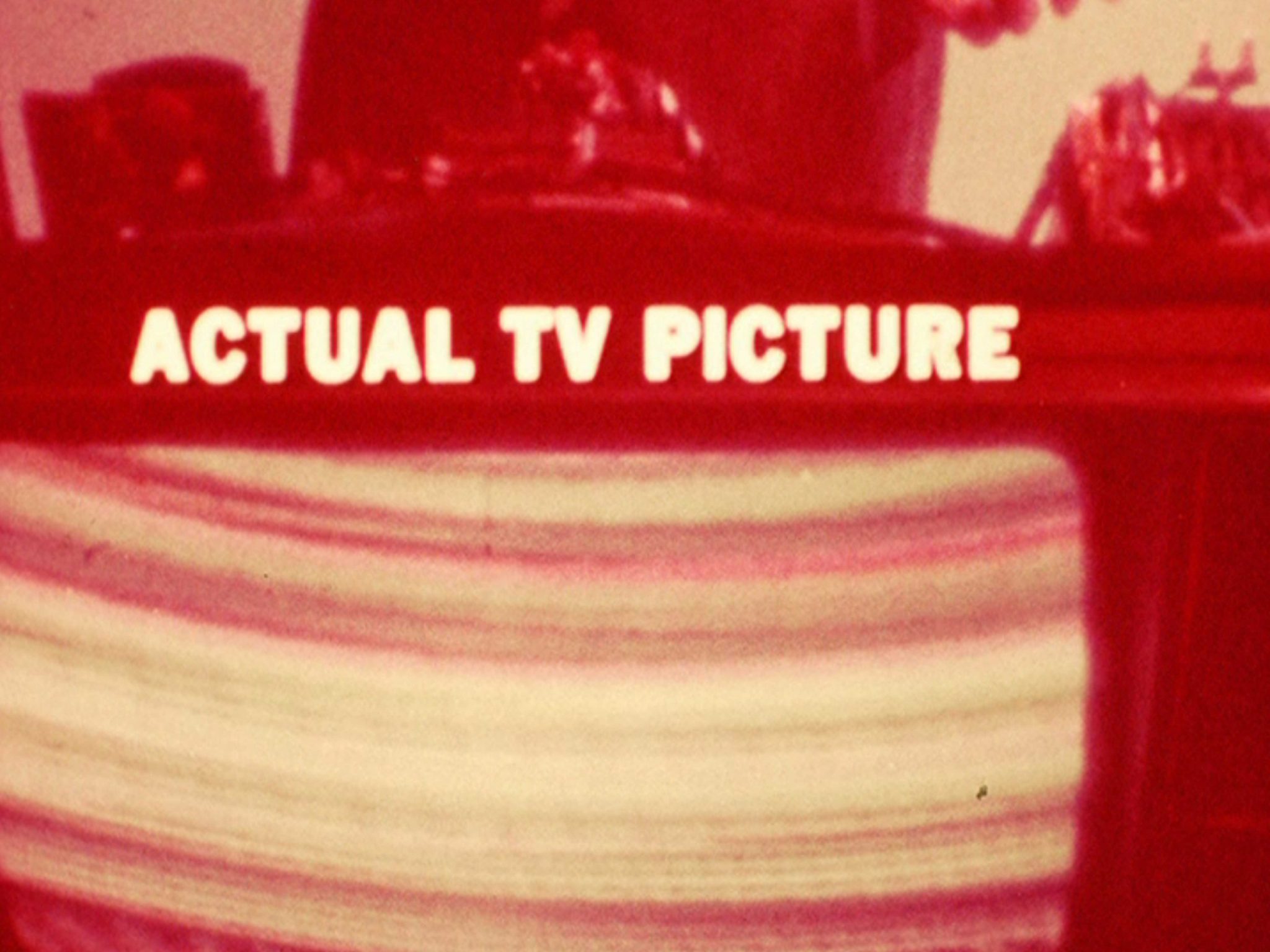

While sex, and in particular the history of gay sexuality, has figured largely in Jones’s output, it is violence that is emphasised in this impeccably installed exhibition of three videoworks at the Modern Institute’s Aird’s Lane space. Actual T.V. Picture (2013) is a splicing together of two sets of footage from the late 1960s: first, a depiction of aerial bombing during the Vietnam War, the film now faded to green; second a television advertisement in which advancements in miniature transistors are shown, this footage now faded to red, the fate of all Eastmancolor film. The two flicker quickly back and forth accompanied by Morse code-like beeps and loud white noise, as if they are two programmes interfering with one another. Those transistors, we are informed in the press release, were used to mass-produce television sets, but were originally developed by weapons manufacturers: this is TV looking at its own insides, only to find itself networked into a system of violence, a military technology that now broadcasts evidence of itself.

Bay of Pigs (2012) makes further use of documentary, albeit in a more abstract fashion, using a kaleidoscopic mirroring effect on clips from Cuban-made film Girón (1974), a film ‘captured’ by the CIA (and accessed by Jones in the CIA library) on account of its documentation of the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion from a Cuban point of view. Though Jones’s treatment of flying war planes crossing the skies effectively disorientates, playing on the misrecognition that takes place for the video’s owners, who see themselves depicted as the enemy, it is edited in such a way as to render the aeroplanes abstract, and an accompanying soundtrack of numerical codes exacerbates this almost mathematical, patternlike treatment of violence. Shoot Don’t Shoot (2012) is the most successful film here because it creates complex misreadings of a violent situation at pedestrian ground level, having been taken from an old police training video designed to instruct gun-wielding cops as to the right moment to take down a suspect. The unusually didactic voiceover, and its assertion that ‘you are the camera’ allows one to experience the camera as weapon guiding our actions, rather than the other way around, somewhat like an early shoot-em-up videogame. We see two disastrous scenarios cut together, sometimes on top of one another, both following from ‘our’ decision to shoot the suspect. Part of the dilemma of viewing this film, however, comes from the fact that our suspect, who we are told is “a black man wearing a pinkish shirt and yellow pants”, looks like a handsome, sideburned TV star from an old cop show, and the searching way that the camera follows him ignites something like desire, if only to see him in the crowd. The way that he puts his hand under his shirt might signal the dangerous presence of a gun, or a form of peacockish sexual display. Jones is highly adept at revealing and manipulating the glitches of machines, but his work becomes doubly powerful when these are layered with moments of confusion that speak to desire and disorientation – the human glitches left in material, which Jones has unparalleled skill at unveiling and handling.

This article was first published in the Summer 2013 issue.