Referring to the ‘object-ness’ of new painting, Donald Judd once wrote, during the polemical heyday of Minimalism, that ‘almost all paintings are spatial in one way or another’. He was speaking of practices, mainly by dudes, that treated painting with tongue-in-cheek medium- specificity: specifically, Frank Stella’s canvases – the shapes of which were reflected by their interior concentric lines – and Ad Reinhardt’s tricky, chockablock monochromes. But what should we make of Puerto Rico-based artist Zilia Sánchez, whose paintings, also made during that era, are so spatial and so shapely, literally? They’re redolently minimalist yet simultaneously contrary to it. Artists Space’s press materials refer to them as a ‘queering’ of that movement, and with their sexual, almost anthropomorphic protrusions and curves, the label fits. They offer a refreshing, feminist retort to standard art- historical narratives.

Born in Cuba, Sánchez studied at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro, where, in addition to painting and drawing, she designed furniture and theatre sets. Later she became involved with anti-Batista movements and aligned herself with a group of intellectuals and artists known as Sociedad Cultural Nuestro Tiempo. Moving to New York in 1964, where she lived for eight years, Sánchez began making her most identifiable work: one, sometimes two or more canvases joined together, with amorphous shapes of colour extending out towards the viewer, as if a fist was pushing from behind the canvas, stretching the surface to its breaking point.

With their sexual protrusions and curves, Sánchez’s paintings offer a refreshing, feminist retort to standard art- historical narratives

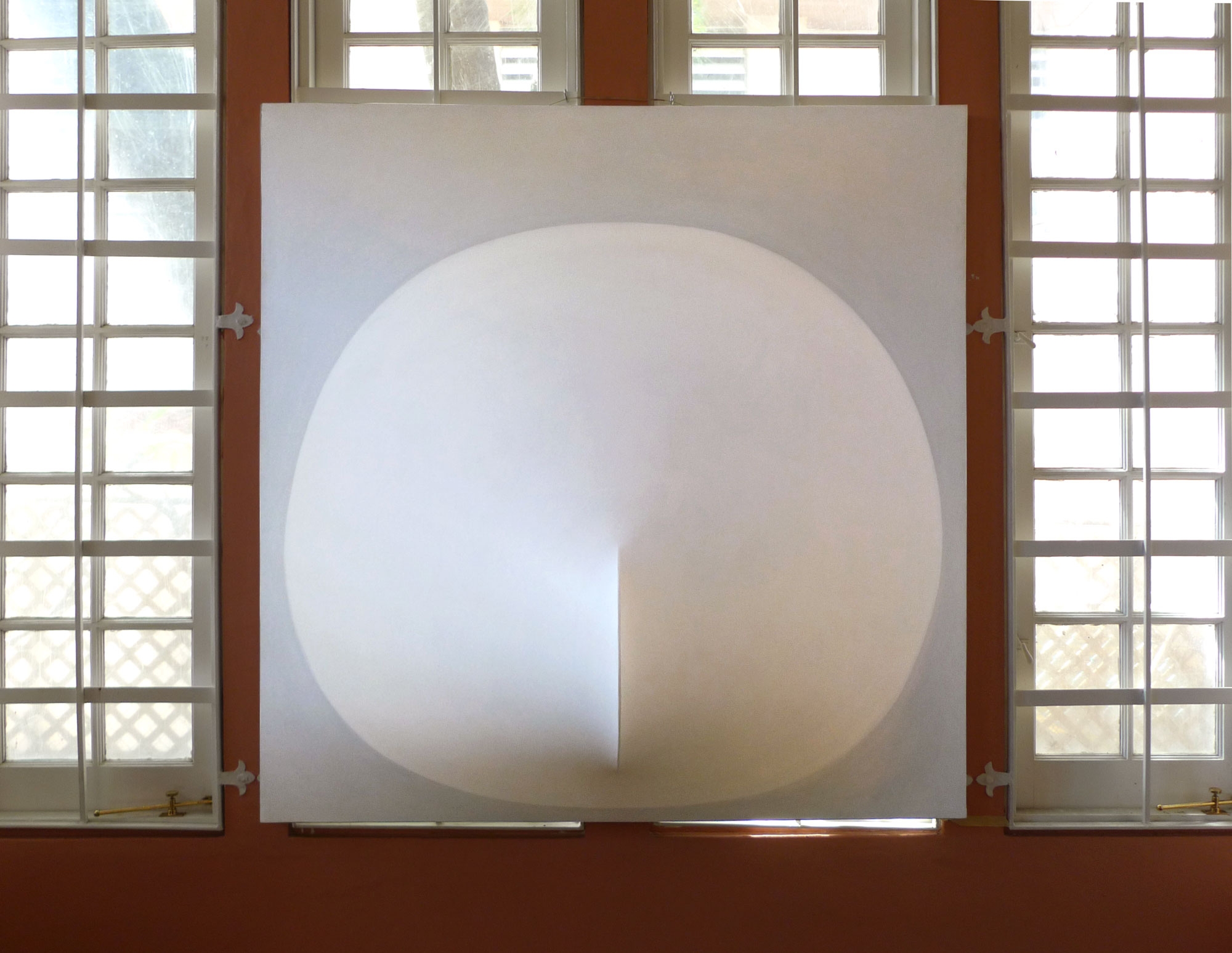

Taking a cue from Lucio Fontana, one of her professors, this unique three-dimensionality is most simply employed in the earlier works on display, such as Mujer (de la serie el Silencio de Eros) (1965), a blue painting that features a white curvy oval reaching almost to its edges. As the canvas is pulled over a wood (sometimes plastic) armature attached to the stretcher frames, a very vaginal slit pushes forward several inches from the wall. With Amazona (1968), too, the effect is suggestive, as if the head of an erection was pressing against the back of the painting, charging the work’s curving, black foreground with a distinct erotic energy.

Later works such as Topología Erótica (1976) push this effect further. With nary a straight line in sight save for the edges of the canvas, the work’s three bulbous forms resemble curved cones, or some kind of cross between a breast and a penis. Another painting in the Erotic Topology series, from 1978, features two ovals of light pink, blue and white, one pressed atop the other, set against a dark blue background. An appendage reaches down from the top, while the bottom curves up, almost to receive it, with a swollen, circular form, like a kinky sex act between two consenting canvases.

Clean-cut, geometric abstraction this is not. Rather, this survey of work is so rife with genital forms that it would make Judd blush, proving that Minimalism was not just analytical but, in this case at least, anatomical as well.

This article was first published in the Summer 2013 issue