Looking at the artist’s ‘Early Photography’ exhibition in the age of facial recognition

In a 1985 interview with Aperture magazine, artist Richard Prince said, ‘I’m interested in what we produce and what we consume. What we think we own and what we think we control.’ You’d think, or hope, that, at the very least, you’d own your own face. Well, sometime in the 2010s, it’s likely that your face found itself under the ownership of Clearview AI.

I became aware of the scale and reach of Clearview’s facial recognition software through Your Face Belongs to Us, Kashmir Hill’s thrilling investigation into the secretive US startup, which was published in September. Clearview boasts the biggest inventory of faces in the world: 30 billion scraped from the internet (without consent, of course) for use as training data for their machine-learning system. Take a photo of someone, run it through Clearview, and you’ll see every photo of them that is or has ever been on the internet as well as their geolocation. Despite being sued in several US states, the UK and the EU for violation of biometric information privacy acts, Clearview continues scraping.

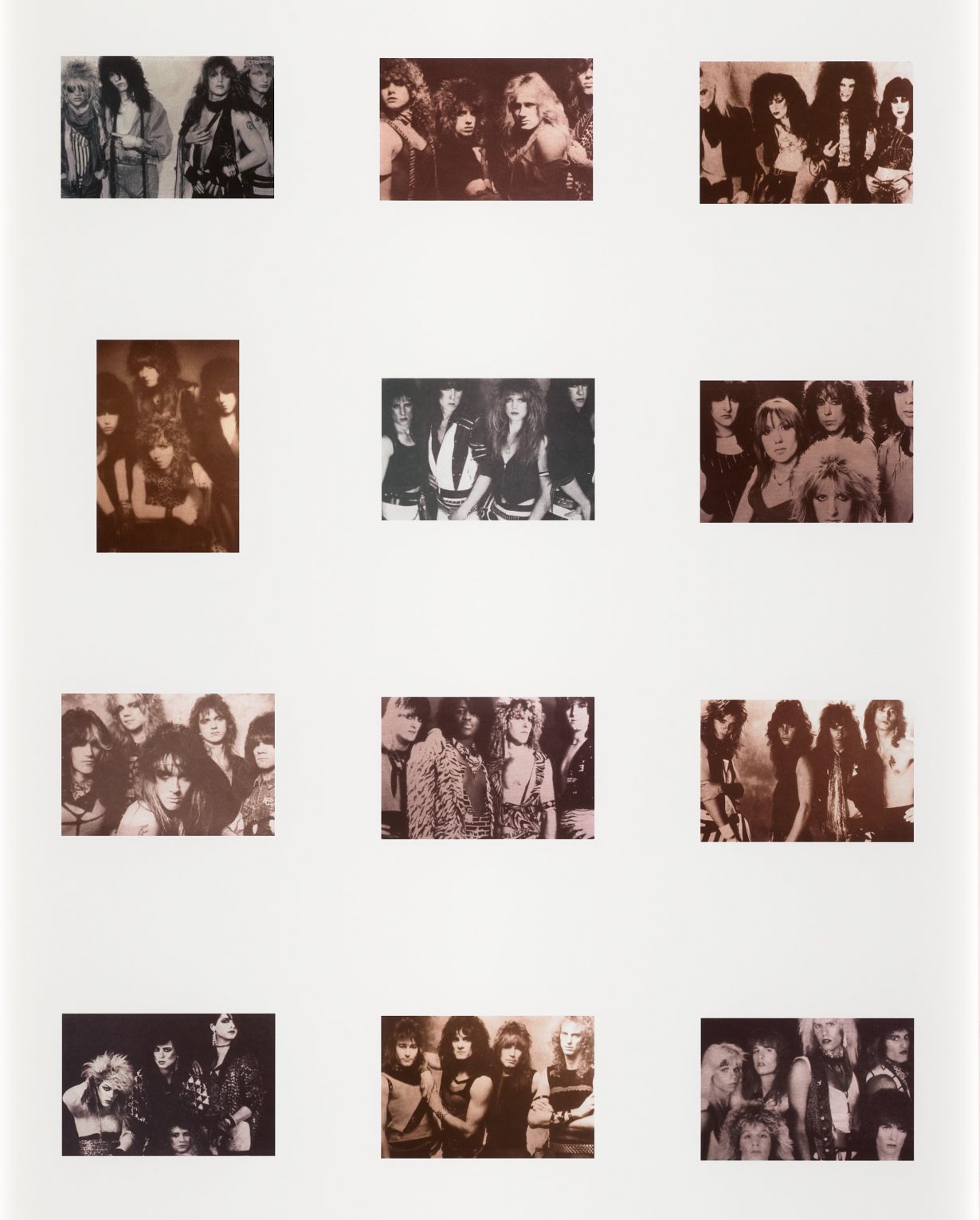

With Hill’s exposé on my mind, I attended two Richard Prince shows at Gagosian in London. The Davies Street gallery hosts The Entertainers, a dozen re-photographed publicity shots of actors, models and singers with manipulated colours, contrast and focus. At the Grosvenor Hill gallery, Early Photography, 1977–87 gathers Prince’s first forays into re-photography, with cowboys, girlfriends and other ‘Gangs’. This exhibition shows Prince developing his infamous technique, where, he says in an interview with Nancy Spector, the camera turned into ‘an electronic scissor, creating a seamless surface without scotch tape’. With this Prince acquired, relocated and (re)presented images from advertising and magazine editorials. Is Prince’s ‘electronic scissor’ the progenitive scraper? The technique has led to Prince being embroiled in lawsuits around theft and privacy violation. Leaving aside the legality of his practice (and Clearview’s, for that matter), I saw Prince’s Early Photography as adjacent to, even prophetic of, developments in facial recognition.

Prince’s ‘Gangs’ bring together images from various contexts into visually coherent grids. The nine photographs in Criminals and Celebrities (1986) are united by a shared gesture – a raised hand obscuring the face – used by celebrities and criminals alike to shield themselves from the paparazzi. The two social groups – one worshipped, the other outcast – are equivalised when categorised and read only by visual analogy. The taxonomic ‘ganging’ of shared traits nods to photography’s early use as a scientific and sociological instrument, ‘truth’ telling by nature of its mechanical, and apparently infallible, duty to report what lies before it. Human faces have been the subject of multiple theories that tried to map a scientific ‘truth’ onto them, revealing dispositions and proclivities from IQ to criminality. Inevitable, then, that the encoded face and encoding machine would coconspire.

These intersecting histories of cameras, smart surveillance and AI are one of the subjects of Jill Walker Rettberg’s book Machine Vision, also published last September, in which Rettberg, through ethnography and media theory, explores how algorithms are changing the way we see the world. She references Alphonse Bertillon, the police officer and criminologist who invented the mugshot, whose ‘anthropometrics’ combined photography with mathematical measurements and classifications of people – a racist, misogynist and ableist physiognomic legacy that still lurks in today’s AI systems. While Rettberg thought the pseudoscience informing machine vision would lead to mass mistrust of images, she writes, the opposite has come to be true.

Prince was fascinated with TV shows like To Tell the Truth (2016-22), Truth or Consequences (1950-88, over various iterations) and Who Do You Trust? (1957-63) –crass game showsthat capitalised on their audiences’ (distinctly postmodern) longing to uncover a shred of authenticity and truth in an increasingly mediated world. ‘To tell the truth was our issue,’ Prince told Jeff Rian in an interview for Purple magazine. ‘But how to tell it?’ Machine-learning systems are governed by the notion of ‘ground truth’ that decides what machines can ‘see’. Trained on data labelled ‘ground truth’ (indicating the gold standard of each object-image), the model is then introduced to new images and must decide for itself whether they fit the object definition. The logic behind object and facial recognition is the same: Rettberg explains how CelebFaces (a database of over 200,000 celebrities’ faces, each linked to 40 attributes) sorts gender according to the ‘ground truth’ of male – anything else is ‘false’. Additional ‘truths’ range from the benign, ‘wearing a hat’, through the undeniably biased ‘attractive’, to the outright derogatory.

Early Photography, 1977–87 contains numerous grids of images illustrating what we might now see as ‘ground truth’ (mis)recognitions. Prince identifies and classifies pens, pocketbooks, hair accessories, gloved hands and bejewelled decolletages. Untitled (Fainted) (1980) is a particularly sinister grouping of what appear to be four different unconscious women (Prince’s non-consensual practice all the more violating in this context). There are also slippages, as in Criminals and Celebrities (1986), where one ‘truth’ overwrites a more fundamental cultural difference. Bitches and Bastards (1985–86, in a title not dissimilar from CelebFaces search criteria) assimilates the bravado of male rock bands with drag. The face machine cannot conceive of non-binary transgressions, it only sees the measurable volume of a shaggy hairstyle.

When image turns into infrastructure, scholar Kate Crawford notes in her 2021 book Atlas of AI, the meaning or care given to a person or context is erased as it ‘becomes part of an aggregate mass that will drive a broader system’. For Prince, the equivalence of criminals and celebrities, unconscious women and luxury watches, is not an unfortunate consequence but the driving intent. Prince was aware that magazine images of people tend to be accompanied by readers wondering what that person’s ‘other’ or ‘separate’ life outside of the magazine is like. With no care for this other life, Prince’s images are concerned only with magazine life, that which is just ‘another accessory. It’s like a hat or a glove, a ribbon, a bow, a watch, or a pen,’ Prince said in a 1982 interview. The found faces are a doubling of individuals into ‘things’ or ‘brands’, prefiguring an attention economy where we too make a thing of our (magazine or rather online) lives to bolster personal brands.

Returning to Clearview, and the ickiness of knowing they own your face, ‘Who we are is in our face,’ Kashmir Hill says in an interview with The Verge. Yet as anyone with a face that reads as false to the ‘ground truth’ of Caucasian males will know, your face becomes a type imposed upon your subjecthood. Prince’s Early Photography exhibition, steeped in an ambivalent nostalgia for the generic-stock-image-as-object, presents a disquieting warning to our digital doubles: when your face is turned into a thing, it is a thing-among-things, and you’ve no control over how it’ll be used. Steps are being taken to establish regulatory frameworks limiting the misuse of machine learning and facial recognition technologies: recent legislation establishing standards for AI safety and security with a focus on privacy, equity and civil rights have passed in the US and the UK. But we are still unable to shake that eighteenth-century conviction that faces are facts: our faces continue to be used to locate, to track, to criminalise and deport – and the stakes are rising.

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor.