Film and theatre sets expand beyond the stage in an exhibition that uses repetition to blur the line between performance and participation

At the ostensible heart of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s exhibition is a transparent stage set for the Bayerischer Staatsoper’s production of Toshio Hosokawa’s one-act opera Hanjo (2004), adapted from Yukio Mishima’s 1955 ‘modern’ Noh play of the same title. Thanks to its transparency combined with stage lighting, the stage recasts the entire opera as a shadow theatre on the back wall of the space. During the day, when it’s not hosting opera, the stage set – which fuses Noh traditions (in the form of a ghostly white bonsai tree) and the demands of an opera set (the stage is on wheels in the centre of the room) – hosts one-on-one tea ceremonies created and performed by Japanese artist Mai Ueda (as part of Tiravanija’s exhibition, but also her own thing). A set, a platform and a sculpture. This, but also that. Actors and audiences swapping places. Like much of the exhibition, it’s there but not there. There’s a sense in which the exhibition has no real ‘heart’, but that instead its component parts have been atomised and dispersed (or ‘decentralised’, as the institution puts it) throughout the Haus der Kunst.

Part of the exhibition unfolds in time as well as space: a selection of seven films, made between 1995 and 2017, screen in succession throughout the day in a room on the Haus’s first floor. The setup is simple: screen, casual seating (beanbags and a few chairs). In keeping with what’s going on downstairs with the opera set, many of the works in this celluloid retrospective are also collaborative productions (with artists with whom Tiravanija is readily associated, such as Philippe Parreno, Liam Gillick, Carsten Höller, Douglas Gordon and Pierre Huyghe). Among the films is Skip The Bruising Of The Eskimos To The Exquisite Words vs If I Give You A Penny Will You Give Me A Pair Of Scissors (2017), the artist’s shot-for-shot remake of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), which was largely set in a Munich bar. Tiravanija’s version was filmed on a set created in his then-gallery, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, in New York. Adding another loop to this eternal return is the fact that a version of the bar from Tiravanija’s remake (which also features cameos by fellow artists such as Karl Holmqvist) is installed in a ground-floor room leading out to the Haus’s restaurant and terrace, complete with the barkeeper, actor Florian Tröbinger – who also plays that role in Tiravanija’s film – offering visitors free Cokes or beers. This, in turn, echoes the constant role reversals between actor and viewer that occurs on the stage set (if you participate in the tea ceremony and see the opera). Which gives the exhibition as a whole the feeling that it operates like a screen that’s being constantly raised and lowered, flickering between scenes of artifice and reality. Propped on the bar is a TV set also showing Tiravanija’s film.

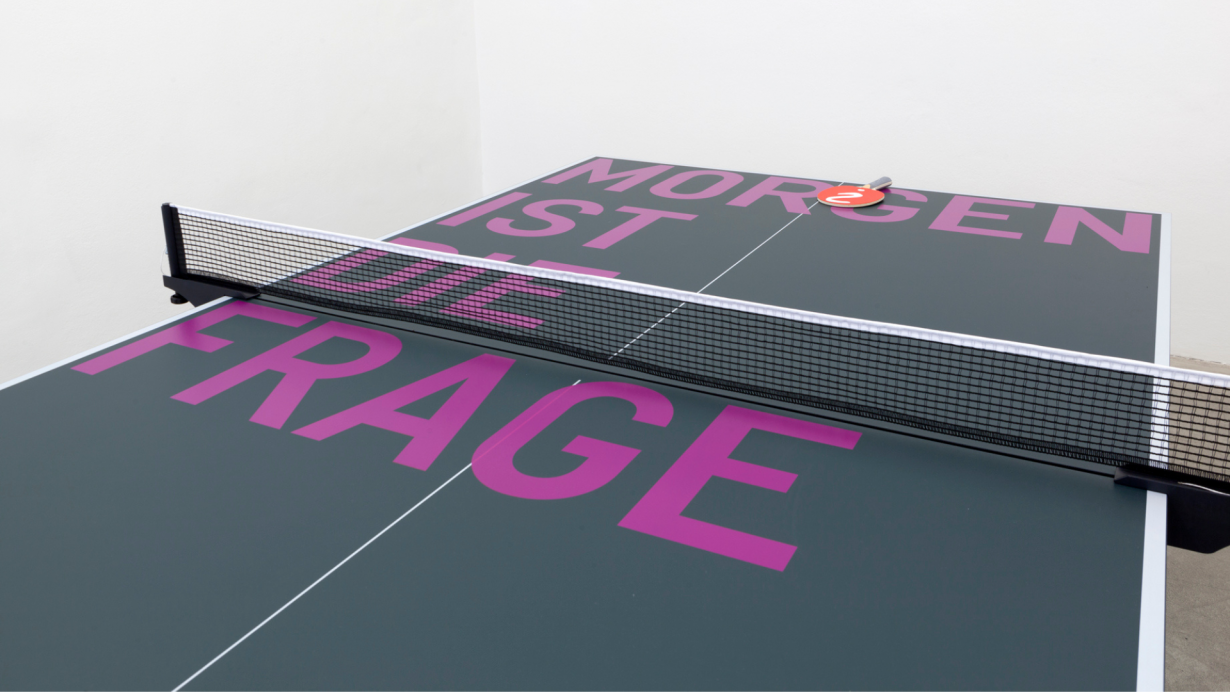

The bar area is housed in the middle of what might as well be a sports hall: the room is littered with Tiravanija’s table-tennis tables – untitled 2013 (morgen ist die frage) (Tomorrow Is the Question) – their tops stencilled with the German words of the title. The work itself riffs off a 1970 participatory work by the Slovak artist Július Koller, J. K. Ping-Pong Club. Here, visitor-participants creating a ‘ping’-‘pong’ soundtrack that bleeds and echoes through the nearby spaces of the Haus itself. Off to the side is a small room in which you can screen-print a selection of Tiravanija’s slogans on T-shirts to take away. These, such as ‘the motionless star and the moving star will meet’, are borrowed from the (English) libretto to Hanjo. During the opera, the slogans are also displayed on screens by the side of the set, while some are spelled out on banners between the columns of the Haus’s exterior that articulate the opera’s central dilemma: ‘My body is filled with waiting’ and ‘I wait for nothing’. Above the Haus’s entrance is a video, untitled 2011 (pay attention), that animates, sometimes word by word, further slogans (in multiple languages) relating to the balance between freedom and repression on which society is built: in Spanish, ‘Uno no puede simular la libertad’ (You can’t simulate freedom).

Hanjo itself documents the ambiguous relationship between two women, one an artist, the other a former geisha who makes daily trips to the local train station to greet a male lover who has promised to return for her, but doesn’t arrive. Through the course of the opera, the dramatic climax of which treats the lover’s actual return, we get to examine the ways in which the women deal with real and imagined worlds, insanity and reason, control and a total lack of it, and a life given structure in the form of endless repetition. Much like the exhibition itself.

Rirkrit Tiravanija at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 5–29 May