Romantic Irony at Arario Gallery, Seoul opens the new space with five Korean artists, grouped under the titular concept of German philosopher Friedrich von Schlegel

Given the number of deep-pocketed foreign dealers who have been setting up outposts in Seoul, it’s been a pleasure to see local firms increase their own footprints lately. After being out of action for a year, Arario has unveiled a gallery with – count them! – seven floors, including its basement. Renovated in high-industrial chic by Jo Nagasaka (Schemata Architects, Tokyo), it stands next to the delightfully odd Arario Museum (an idiosyncratic collection of Korean contemporary artists, YBAS, Jörg Immendorff, Cindy Sherman and more).

First up in the new space is a group show with five Korean artists on the gallery roster – all men, all but one born during the 1970s. Each gets a floor of his own, so it feels like visiting five separate, modestly sized solo affairs. That said, there’s a single theme and title for the proceedings: Romantic Irony, as conceived by the German philosopher Friedrich von Schlegel (1772–1829), a press release informs. An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age (1999) advises that the phrase connoted, for him, ‘an attitude of detached scepticism adopted by the highest “modern” or post-classical art toward its own activity and/or material’. This could apply to a sizeable percentage of today’s art, but no matter: it was a useful frame for the proceedings.

The chief romantic ironist? That would have to be Gwon Osang, who has layered photos atop curving, abstracted human forms that recall those of Henry Moore. In his previous ‘photographic sculptures’, Gwon has tended to use correctly proportioned bodies and applied images so as to craft realistic (and uncanny) three-dimensional portraits. These latest examples, however, bear fractured collages across their surfaces; they are garish and even grotesque. The head of one reclining figure has been built from snapshots of two different models, and multiple small legs adorn her amorphous lower half. Imagine a primitive computer trying and failing to stitch together a body with too few images, and you have a sense of the look.

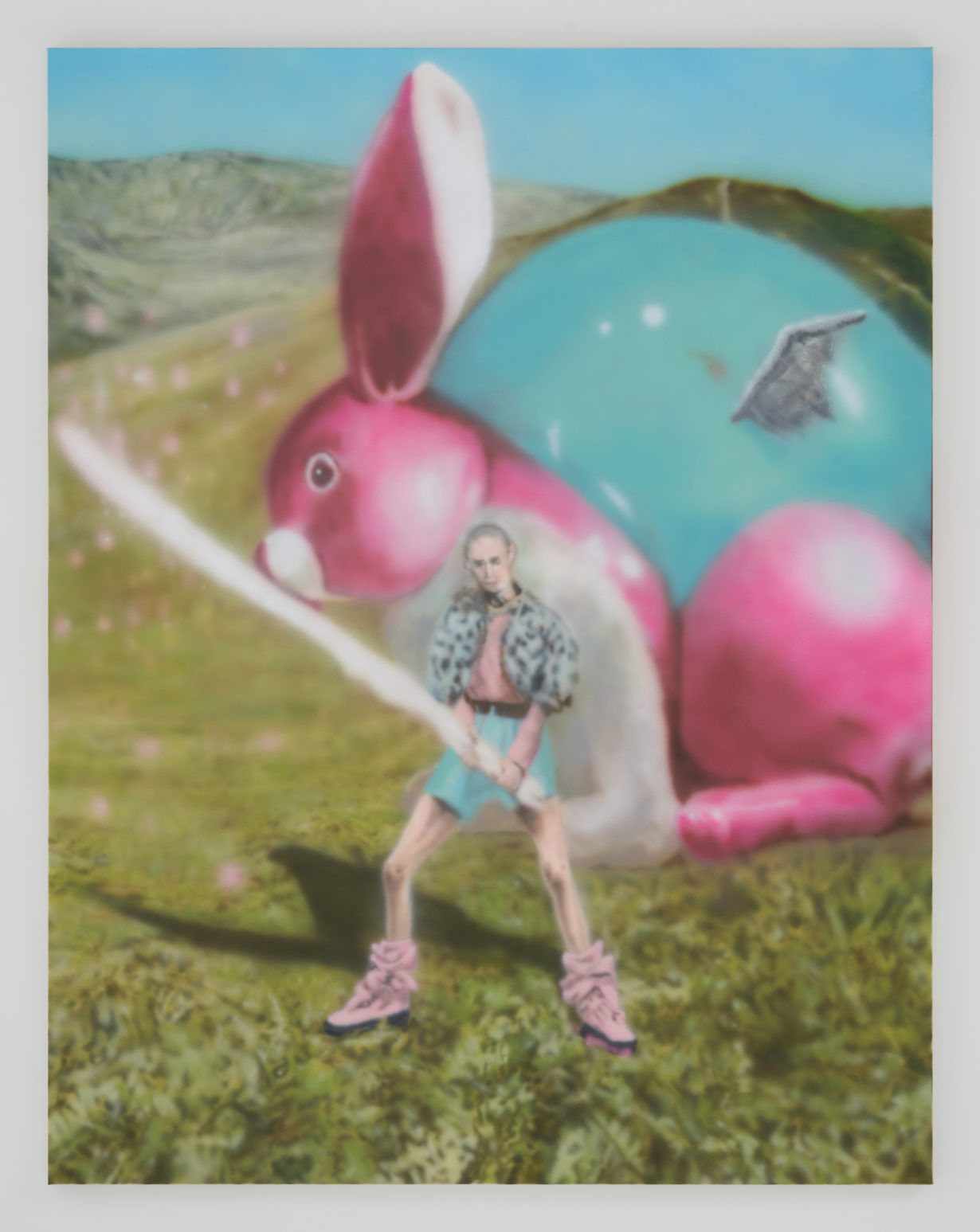

Noh Sangho is also concerned with breakdowns in the legibility and veracity of images. His paintings brew together photos and graphics he generates with AI. Sesame Street’s Elmo holds the form of a crucifix (a meme) before a church window in one airbrushed work; a grinning skeleton sits astride two overlapping horses (an AI glitch) in another. (Both are titled The Great Chapbook 4 – Holy, all works 2023.) As many artists mine disparate sources to make compositions that have an exotic veneer but are ultimately quite tame, Noh deserves credit for making paintings that are genuinely tasteless – as awful as the digital wastelands inspiring them.

The excellent Lee Dongwook’s romantic irony takes the form of shocking self-abasement. He goes through hell in his art. Using pink, fleshy Sculpey clay, he fashions himself as a tiny, usually nude figure undergoing abject trials. In Crane his naked body supports long beams festooned with heads on their ends: a one-man construction site. In Cliff his head rests atop a miniature pagoda. There is an unfinished appearance to many of these sculptures exposed supports, scrappy bits of clay) that makes their harrowing circumstances all the more darkly comic.

A macabre, barely-there humour also lingers in the greyscale paintings of Ahn Jisan, which are rough and patchy, seemingly uncertain whether they want to hold together as discrete artworks or evanesce. (Think Anselm Kiefer lite.) A shadowy figure holds scissors in one hand and a rabbit’s ears in the other in the most memorable piece here. In another, a yellow-haired man grips the back of a water deer (humping it?) as it flies through the snow. These are fine paintings, but it would be nice to see Ahn be even less polite, surfacing the sinister energies that his art seems to harbour.

The best display? That belongs to Kim Inbai, who in an extra-tall space presents four beguiling sculptures. Slices of oddly shaped plywood (a modified outline of the nearby city of Paju) are stacked from floor to the 5.5m ceiling, a map surreally morphed into architecture. Blackboard and Chalk hangs on a wall, its board made of white chalk, its chalk stick painted with blackboard paint. In Metamorphosis two large propellers (one smooth, one craggy) are threaded onto a standing pole – spare parts for some unknown machine. In Hangul, one bears the cryptic words of the resurrected Jesus: ‘Don’t touch me’. This art is about looking and living with doubt – a defining experience of our times – as faith and scepticism duel. Nothing that Kim makes is quite what it first purports to be. As his art reveals itself, it seems to be teaching you, playfully, how to see.