Ruth Beale had to radically rethink her Brent Biennial plans as the pandemic struck. The result: a moving, political, memorial to the victims

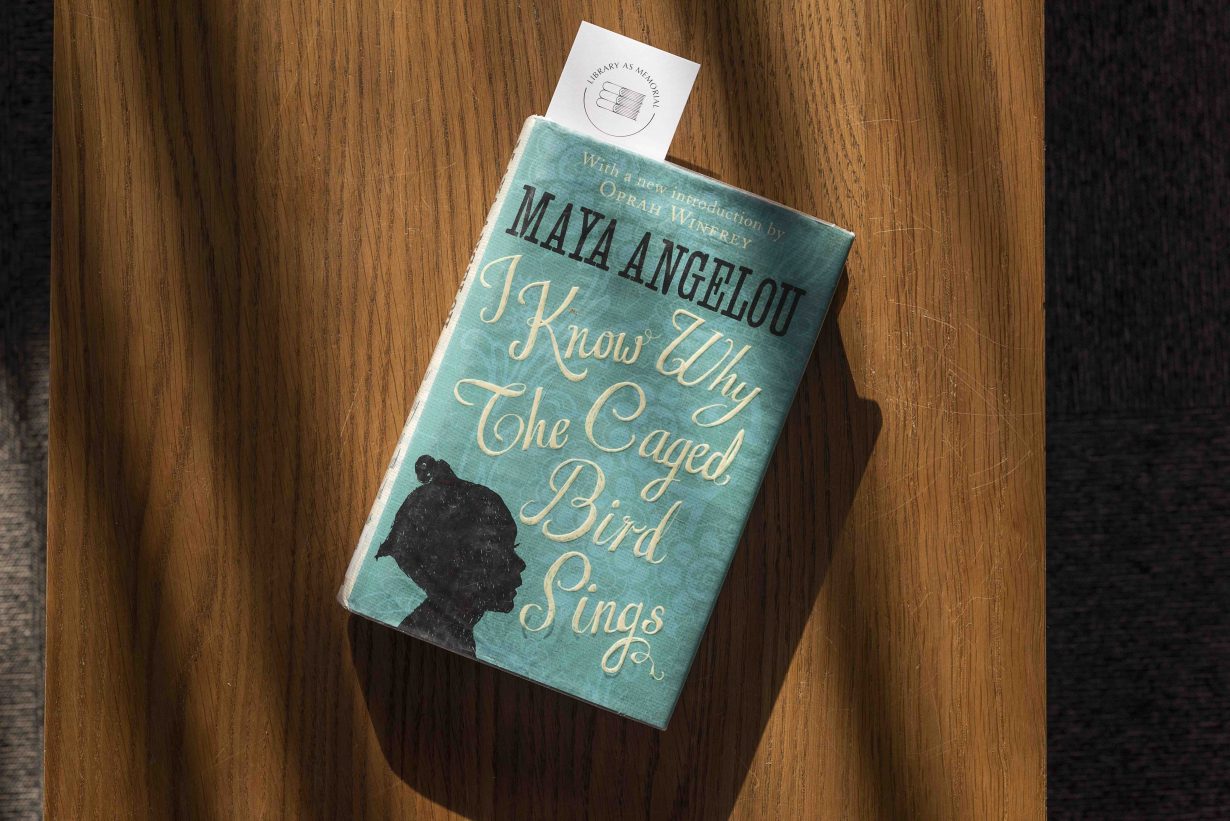

Ruth Beale is a London-based artist with a long-standing interest in how culture, governance, social discourse and representation intersect. She also works in collaboration with Amy Feneck as The Alternative School of Economics. For the Brent Biennial she has produced the Library as Memorial, a collection of 491 books from across the county’s libraries which will be housed temporarily at Kilburn Library. Each book contains a space for the public to dedicate the title to one of the 491 victims of COVID-19 in the borough. Alongside this memorial the artist has made a film documenting the library in lockdown.

ArtReview Your work is a response to the pandemic – can you tell me a bit about it? How did your plans change as the seriousness of the situation developed?

Ruth Beale Up until the pandemic struck, my project had been about imagining the library as a ‘think tank’, so using its resources to question and celebrate the potential of public space. There was going to be a sleepover curated by children from a local school, alongside other events where young people and communities were able to take over the space. Then we went into lockdown, and obviously everything closed. In my own neighbourhood in south London, I kept seeing playgrounds with barriers and tape round them, and I was thinking about how in cities – and this is certainly true in London – our public spaces are shared spaces, and any indoor spaces were dormant during this time. It’s kind of poetic, but there are practical implications too – there are things people really need libraries for, like books, free wifi, computers and work space. In pre-COVID-19 times they were one of the few free, indoor public spaces where you could just ‘be’. So I decided to film and document the closed libraries in a time of pause: empty and waiting, with the chairs piled up, newspapers dated 19 March, even a vine creeping in through the window.

At the same time, I was aware of how badly Brent was affected by COVID-19 – it was the area with the most deaths per capita during the height of the pandemic – and that it was affecting BIPOC communities the most. I was doing creative workshops with members of Brent Youth Parliament over Zoom, and we talked a lot about their personal experiences, and what a ‘new normal’ might feel like, and also about the idea of memorial. I started to feel that the library itself could do that, if people could dedicate books to those who’d died. At times I’ve been overwhelmed by numbers, the infection rates, and deaths locally and globally, and I wanted to bring it back to something personal, to give space to mourn people as individuals.

AR Libraries have become political, contested spaces in the face of austerity. How much did that inform your thinking?

RB I think local authority funding is extremely political, especially looking back to big changes that were made in the 2010s that saw a shift from central government funding to income generated through local rates and council tax. This affected poorer boroughs and poorer households the most, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the top four boroughs in London worst hit with COVID-19 are also in the top six for highest poverty rates. Austerity was killing people before COVID-19, and those same inequalities are playing out now. Then as you say, library services are often the first things to be cut. I think they’re a real litmus paper for the mood of what’s valued and what strategies we’re taking to tackle structural inequality. If it becomes a question of choosing between libraries and essential care, then I think we’re asking the wrong question.

In my collaboration with Amy Feneck, called The Alternative School of Economics, we’ve been thinking and learning a lot about care and social reproduction as we made a podcast about feminist economics. I think it’s interesting to think about public libraries as spaces for social reproduction – that they are places for self-education and civic engagement, whilst providing an important alternative to privatised and corporate space.

AR What did you learn during the process of realising the Brent commission?

RB Choosing the books for Library as Memorial with library staff across the borough was really interesting. I got a little taste of the collections, and the communities, using each library, as well as the expertise of those librarians, whether we were choosing South Asian language books in Ealing Road, or crime novels in Kingsbury, or books from the really good Black history and writing collection in Harlesden. The 491 books are a sort of a capsule version of the library collections, so it’ll be interesting to see which books people choose, which ones have meaning. I imagine I’ll keep learning from those interacting with the installation as we go through the next three months.

AR How does this work fit into your wider practice? There seem to be questions of value, or what is valued, that come through in many of your projects.

RB Yes, a lot of my work is about having conversations about what we value in society, and how we make and remake culture based on those values. I found it really interesting how the idea of ‘keyworkers’ encompassed public services (including privatised ones), gig economy workers, and then people working in food infrastructure from lorry drivers to corner shops. I kept thinking about the overlap between people in these roles and jobs considered ‘low skilled’ by the Home Office with regards to migration. There’s two conflicting value structures at play that at the same time might valorise or victimise the same person.

This year I’ve also been working on a big project producing a radio play that was co-written with prisoners at HMP Lincoln. We used sci-fi as a tool to talk about ideas about freedom, utopias, dystopias, and to create a fiction by taking a scenario to an extreme. Sometimes it feels like we’re living in science fiction right now – it’s easy to see how, say, new laws around COVID-19 restrictions might be abused, or, like Stop and Search, meted out disproportionately to certain people. It raises questions about how we share resources and look after each other, and how we address historical, structural problems. Whilst some people are desperate to maintain a status quo, I think there’s a really interesting and live conversation going on about how not to go back to the ‘normal’ we had before, that artists can be part of.