FAIR GROUNDS at Regen Projects, Los Angeles presents a view of carcerality and state control that teeters wildly between whimsy and nausea

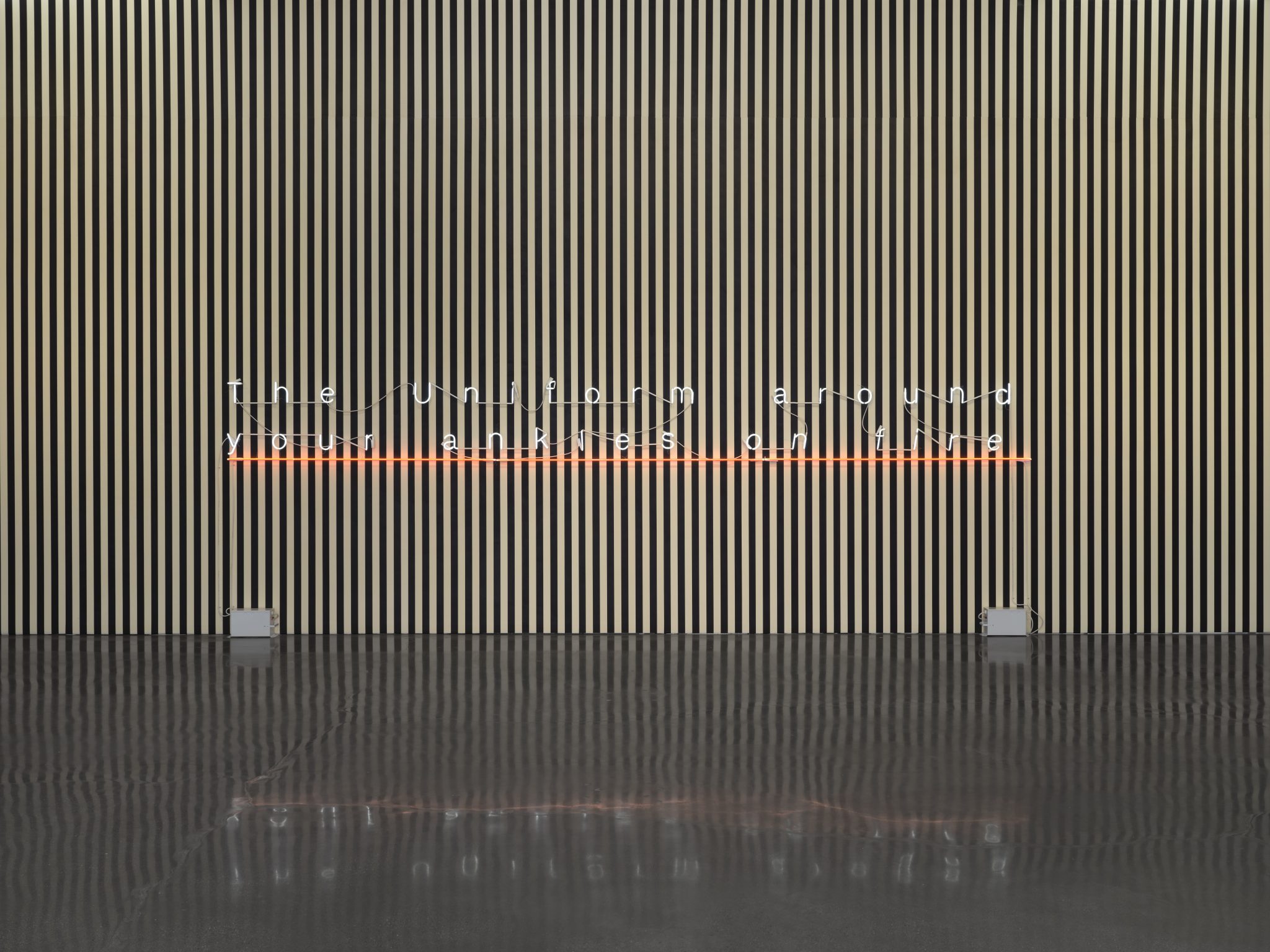

We might think of Sable Elyse Smith’s exhibition as a landscape: the join of the gallery walls and floor looks like a horizon line; a disorienting mass of cream and vertical black stripes line the walls and reflect onto the concrete floor below. Not, in that respect, unlike a Romantic landscape painter’s visual elision of sky and water. These stripes, Smith says, are a reference to the cartoonish carceral uniform, which was historically conceived as a way, literally, to impose prison bars onto the bodies of the incarcerated. In FAIR GROUNDS, this architecture-cum-sartorial mode is rendered by Smith into a funhouse wall as a way to affectively subsume the viewer, who teeters wildly between whimsy and nausea.

Shiny metal, powder-coated and coldly clinical interior prison furniture – namely meeting-room stools – have been imploded into nucleuslike sculptures that look eerily like playground equipment. At the same time, tender photographs from the family archive and a neon poem called Landscape VII (all works 2023) offer moments of sublime visual rest to counter the frenetic prison-stripe wallpaper to which they are affixed. In the next gallery, a dense collection of several blown-up iterations of colouring-book pages featuring cartoon pigeons and thickly illustrated judges explaining the criminal justice system in bursts of speech bubbles and storybook text serve as a continuation of a series of works on carceral pedagogies aimed at children that Smith began in 2013. These screenprinted vivid colouring-book works, scrawled and flooded with errant MS Paint-like lines to colour them in, anchor the rest of the works in the show with their disquieting, yet cutesy, didacticism.

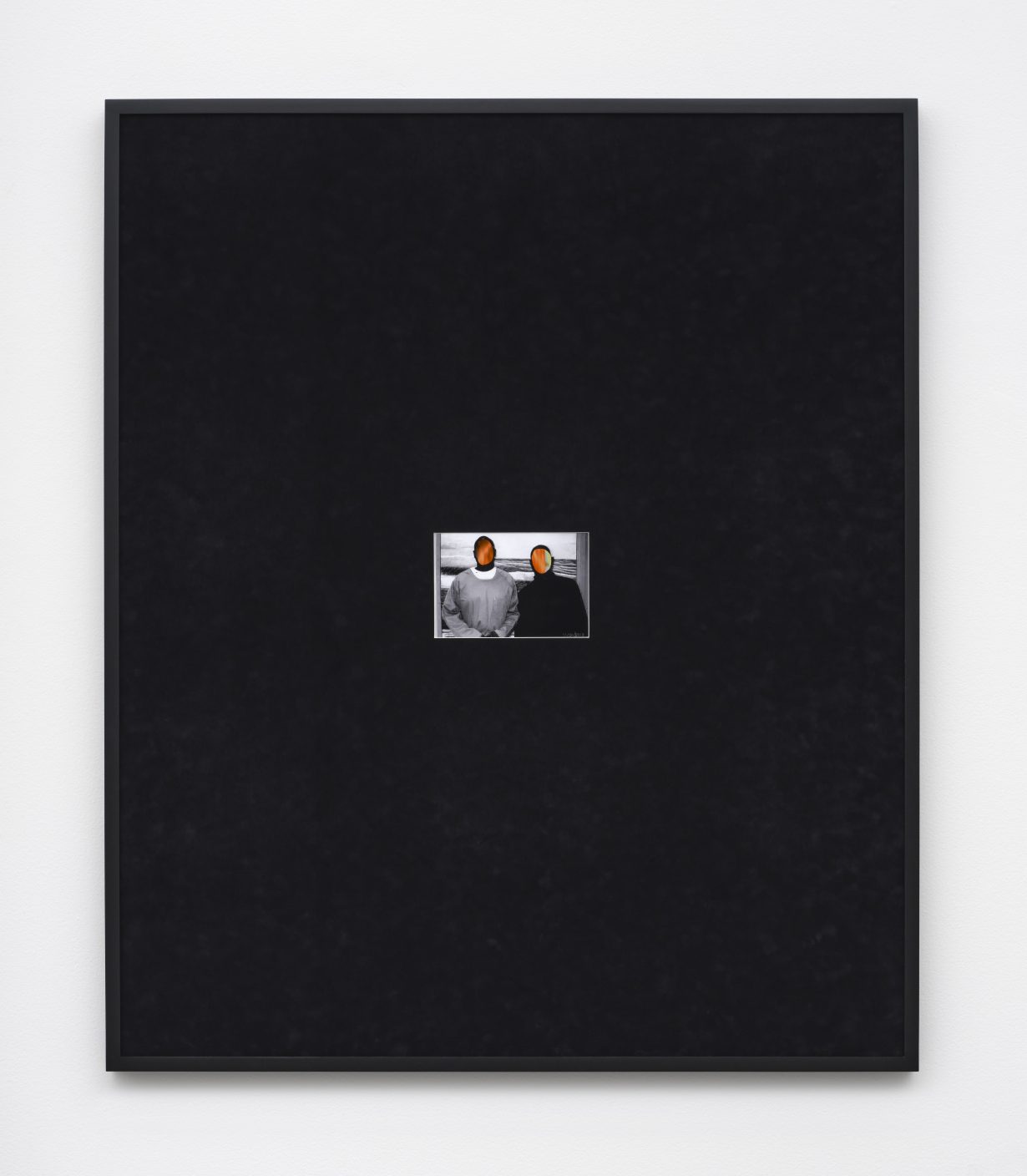

The most compelling works in the exhibition, however, are the ones that take seriously the affective latency of their materials. The series of photoworks, from Smith’s personal archive of her visits to her incarcerated father, all with titles that seem to mark the passing of time, like 9855 Nights, index an institutional apparatus that attempts to assert control even over moments of intimacy and kinship. In the photos, faces are obscured and anonymised by impositions of sunsets, clouds and other romantic facets of landscape. Each matted on its own rectangular swathe of black suede, the digitally manipulated photos seem to rise to the surface from some dark depths. Here, the multivalent qualities of the material rupture the didactic. On one hand, the overwhelmingly large space of the matte around the small photos further emphasises the uncrossable emotional distance of separation from an incarcerated loved one, and yet at the same time suede is a material that nevertheless registers physical touch. In the light, standing at a distance and at the right angle, you can see where it’s been handled. You can see what it might feel like.

Bracketed by the polysemous title, Smith’s conceptual meander between landscape metaphor and the bleak carnivalesque seek to invoke the ways in which carcerality, surveillance and other state apparatuses of control become the landscape of anti-Blackness itself. Smith cites scholar Christina Sharpe’s evocation of weather as a description of ‘endlessly repeatable events… the totality of the environments in which we struggle; the machines in which we live’. If viewers are to accept this ecological metaphor, the atmosphere of anti-Blackness, as Smith sees it, is diffuse, yet powerful in its ambient totality. Even though weather has never been invisible, Smith’s work proposes a materialisation of these forces; an endless, rolling storm distilled down to these objects.

FAIR GROUNDS at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, through 26 October