A new show at Gagosian Athens explores the tension between the boundless dimensions of time and space and the limits of human perception

On the first floor of Gagosian’s Athens townhouse stand three modest sculptures. Each presents a fractured block of clay, its surface a dull meteorite silver, on a low and unfussy wooden plinth. A roughly torn photograph of the night sky is trapped beneath each brick like a bill beneath a paperweight. Through this simple combination of mundane materials with cosmic referents, Sarah Sze establishes the tension that animates her work: between the boundless dimensions of time and space and the limits of human perception.

The title of the series, Proportioned to the Groove (2019), is taken from a poem by Emily Dickinson that meditates on the incommensurability of love with the physical world. If ‘love is all there is’, Dickinson asks, then how do we proportion it against people and things? How do we put it into perspective? As Dickinson hints that love is too much for the body to bear – that its burden is not proportioned to our ability to hold it – so Sze’s bricks seem to break under their own symbolic weight. Yet the night sky was photographed at the moment that the clay was fired, has been printed onto cheap paper, has been literally pinned down. It might be argued that time and space are real only when related to materials and subordinated to consciousness. Or, in Dickinson’s terms, love must be scaled to the body if it is to be felt.

Dickinson is also responsible for the title of the polished steel floor sculpture Wider than the Sky (2021), a version of Sze’s monumental homage to prehistoric ruins at Storm King Art Center in New York State, scaled to these more domestic dimensions. It is the brain that exceeds the sky in Dickinson’s poem, and the placement of Sze’s parabolic stone circle in a room ringed by floor-to-ceiling windows allows it, too, to reflect and expand the landscape beyond. As henges function as cosmic calendars, so the paradox of this sculpture consists in the capacity of a singular material object – whether brain or ring of standing stones – to count itself king of infinite space. The confusion of mind and matter is like Vladimir Nabokov’s assertion, in Speak, Memory (1951), that his love for his wife exceeds the distance to the stars.

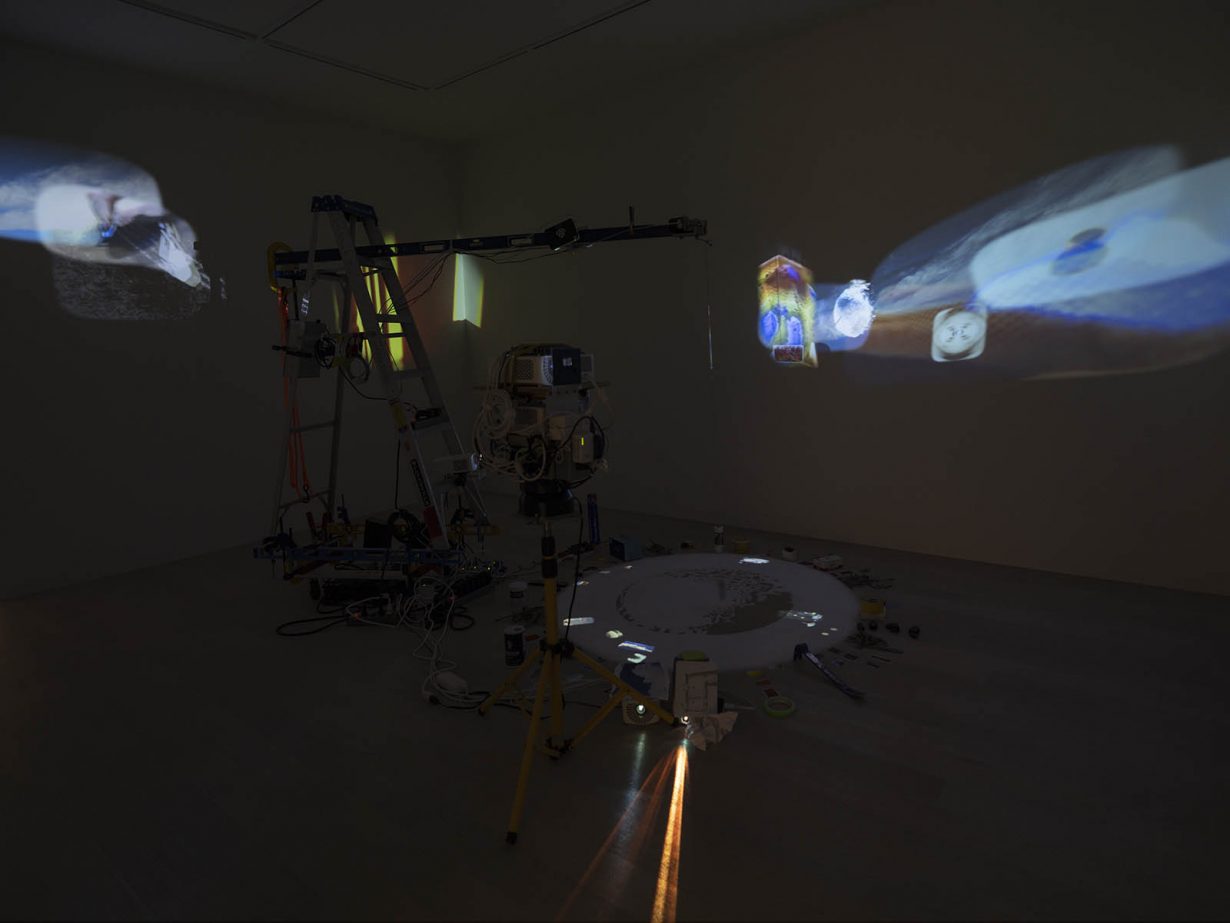

Sze’s work rewards reference to literature because she is concerned with the same problem as poets: how the organisation of such everyday objects as words (or clay bricks or magazine clippings or tinfoil) into new sets of relation can conjure the irreducible strangeness of being. This impulse finds its most literal expression in the room-sized installation Travelers by Streams and Mountains (2021), which combines video projections, torn scraps of paper, a swinging pendulum, a stepladder, adhesive tape, stones and other objects into an experience of visual overload. There is too much to process, and so the work relies on the same precarious and shifting balance between constituent elements that distinguishes good poetry. The feeling it provokes is of being suspended between certainties, caught somewhere between the realms of thought and things.

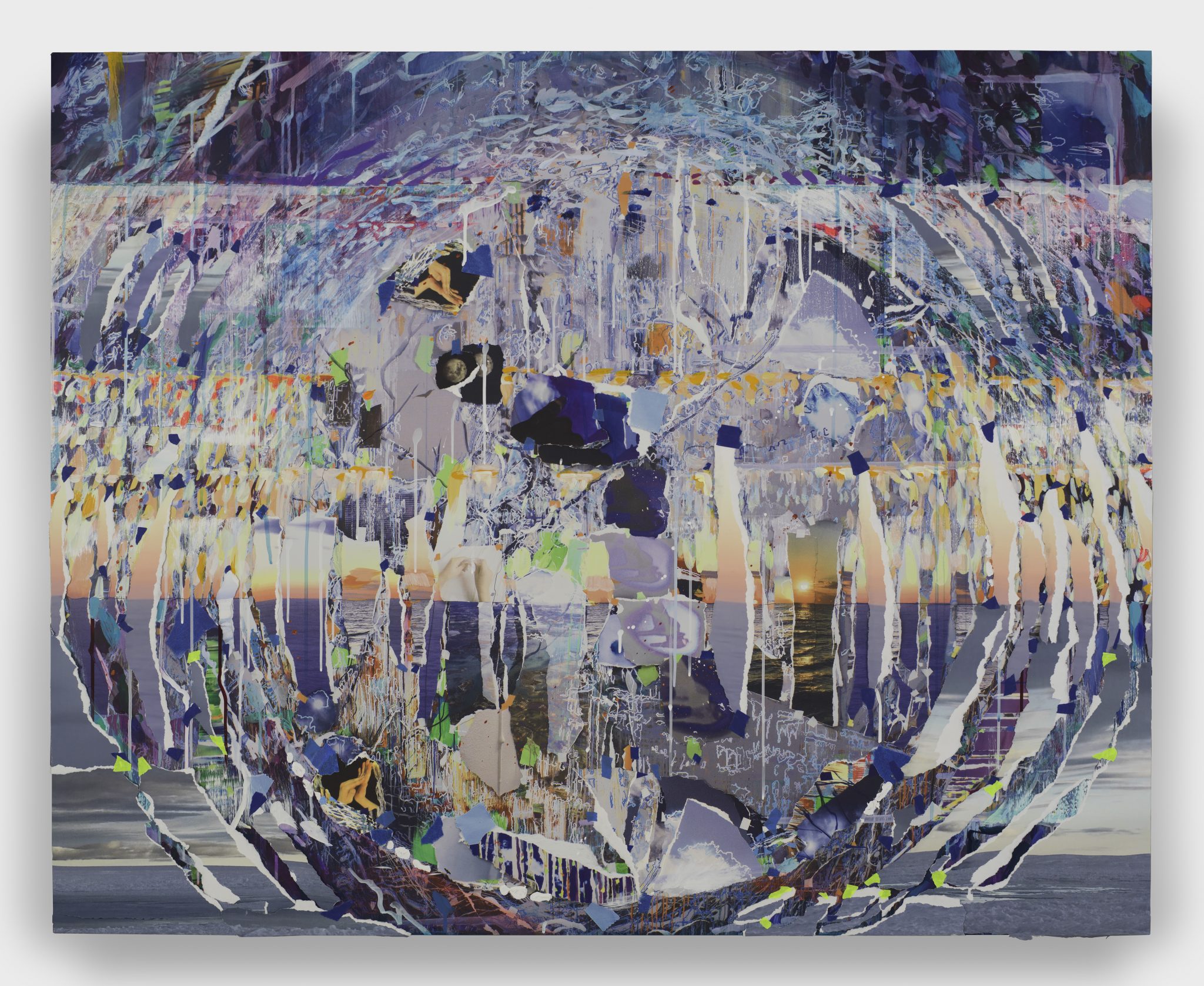

This relation between the chaos of the world and the order that our minds impose on it finds best expression in the ten paintings hung through the gallery’s two floors. They are similarly maximalist, with digital prints, paint and torn images (hands, skies, roads) layered onto thick wooden boards. In each case a horizon line suggests a landscape, but the dominant composition is set by a still image of either fire or water at the work’s centre from which it ripples out into the spiral patterns that are characteristic of Sze’s work in any medium. In the standout Signature Echo (2022), radiating lines of flat brushstrokes in vivid oranges, blues and yellows are reminiscent of the swirls that give Van Gogh’s late paintings their sense of a living force running through whatever objects they happen to represent. Another poet, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, comes to mind: ‘My soul radially whorls out to the edges of my body according to the same laws by which stars shine’. The same force runs through all of Sze’s work, however difficult it is to disentangle from the material it organises: something about balance, proportion and the distance between things.

Sarah Sze at Gagosian, Athens, through 20 October