Like an updated version of the Enlightenment wunderkammer from which curator Brian Dillon takes inspiration, this exhibition mixes artworks and illustrations, objects and artefacts, science and natural history, from the fifteenth century to the present day.

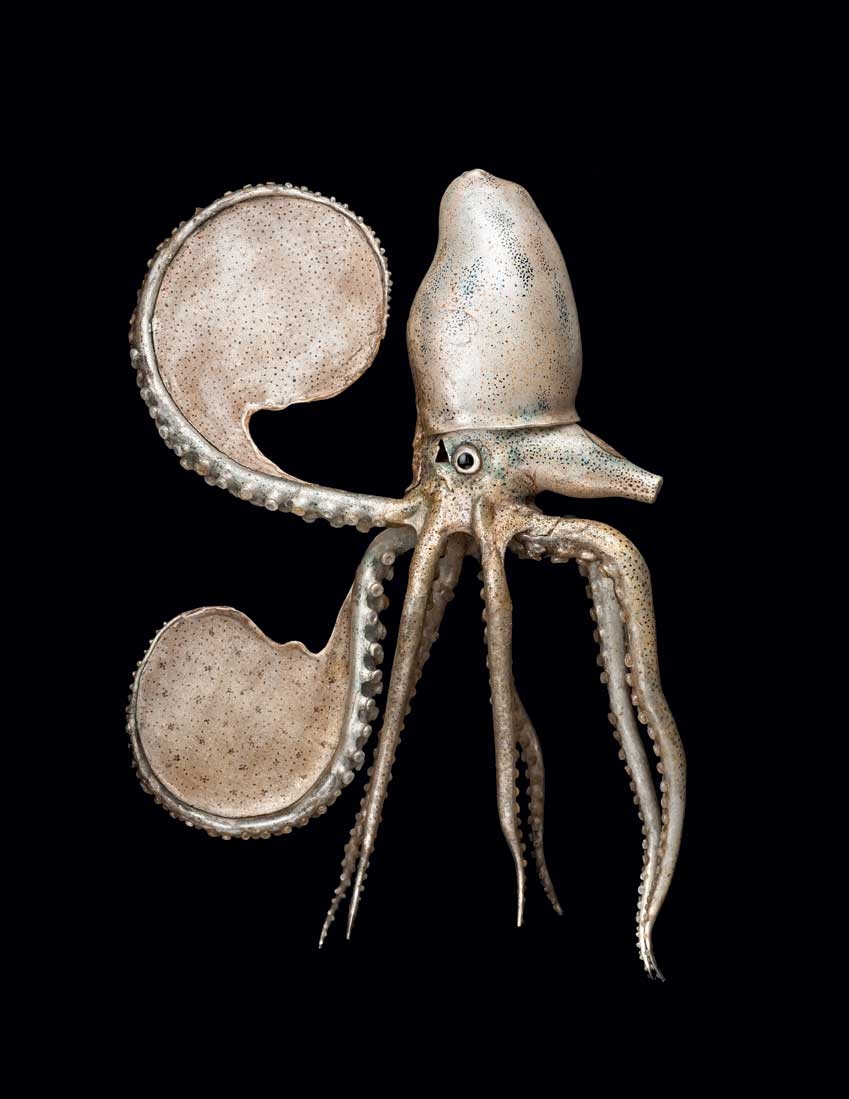

There are drawings by Leonardo, a cabinet of the exquisite glass models of sea life by Victorian father-and-son duo Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a sculptural arrangement of radiometers by Nina Canell (The New Mineral, 2009) and a collection of photographs of popes looking through telescopes, presented by Laurent Grasso.

The overarching title may seem broad, but it’s curiosity of an intellectual and creative kind, rather than a prurient one, that is the focus – perhaps with the exception of Miroslav Tichý, whose furtive photos of women, taken with homemade cameras, manage to be both.

Judging by the packed galleries on my visit, it’s a curiosity that the general public seem to share, although the considered selection of exhibits here is obviously key; perfectly balanced to highlight how objects and artworks can add context and meaning to each other.

In its usual setting of South London’s Horniman Museum the taxidermied Canadian walrus, bought by the museum in 1893 (and filled almost to bursting because at the time it was not clear that loose folds of skin were an anatomical feature), is an overstuffed exhibit in a room full of other stiff, stuffed creatures.

Here though, alongside Dürer’s fantastic etching of a rhinoceros from 1515, in which the rhino’s thick wrinkles are similarly misrepresented as tortoiselike armour plating, and with Robert Hooke’s 1665 drawing of a gigantic flea (from the first English book to show objects as seen under a microscope), the walrus appears less of an oddity and more heroic.

In the above company Gerard Byrne’s cleverly ambiguous film Figures (2001–11) and photographs Connecting Shapes (Three Part Analogy) (2001–), depicting Loch Ness and its legendary inhabitant, also gain extra potency in their blurring of what is fact and what is fiction.

Whereas some exhibits are more obviously artefacts – 1930s Angolan fertility dolls given to girls at puberty – and others more obviously art, such as Nicolaes Maes’s trompe l’oeil Dutch genre painting An Eavesdropper with a Woman Scolding (1665), the most interesting are those that already encompass the two, such as the work by Agency, the Brussels-based initiative coordinated by artist Kobe Matthys.

Over the past 20 years Agency has collected and presented examples of legal controversies (mainly in relation to intellectual property) over how ‘things’ are classified in terms of nature or culture. Here they have selected cases that question the role that systems and processes play in what constitutes an artistic ‘arrangement’.

One example is the legal case brought by the Harold Lloyd corporation against Universal Pictures for copyright infringement of a sequence performed by Lloyd in the film Movie Crazy (1932), involving a magician’s coat, by a similar scenario in the 1943 film So’s Your Uncle.

The examples are presented in the form of a library of indexed box files (containing documentation on the legal cases– written summaries, photos, film clips, etc) that can be selected and explored at leisure.

In one sense this exhibition may be looking back to a seventeenth-century concept of engagement with the wonders of the world, but it’s also a form of engagement that’s increasingly contemporary in a general context, where currency in information is less about discovering or gaining access to it, and more about how that information is selected, collated, curated and presented to us.

This review originally appeared in the September 2013 issue.