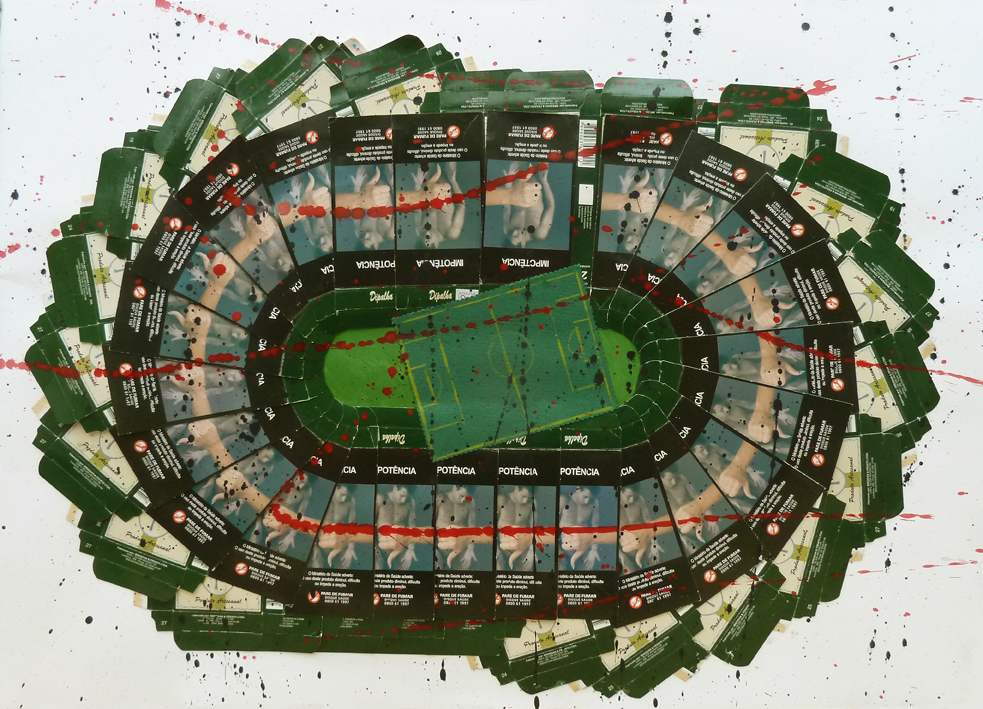

Ahead of the 2014 World Cup, ArtReview asked Felipe Ehrenberg to keep a diary. The resulting pages, collectively titled Fi Fa Fo Fum, are reproduced below this interview.

ArtReview When we first discussed the project we made reference to your Concomitancia series from the early 1970s. You were one of the early adopters of mail art and these works were sent back to artist colleagues in Latin America and elsewhere from the Devon farmhouse you and half a dozen or so other artists and thinkers had colonised at the time. In a way the missives that we’re publishing here are a reversal of that journey. What sparked your interest in using the postal system?

Felipe Ehrenberg Well, we had to use the tools we had at hand and the Post Office – the model of all postal systems is England’s of course – was there and allowed us to establish long-distance contact between artists all round the world. Mail art was one of the very interesting effects of art’s rebelling against the status quo of the time – the established art market, whatever it is – but even the people that were targeted to receive some of these things didn’t think about them as art. They were just very pleasantly surprised. So this series, Fi Fa Fo Fum, these letters from Brazil, have the same look and spirit. They are similarly old-fashioned collages. What I tried to do was something that you could not emulate even though we’re now living in the Age of the Image (which I think is now more important than the Age of Writing). You can replicate almost anything with Photoshop, but these things I don’t think you could.

AR How did you come to be in England?

FE It was as a consequence of Mexico’s 1968 student rebellion. As it was on the eve of the 1968 Summer Olympics, the government and the army repressed a demonstration in downtown Mexico City. They say only 40 or so people died, others have put the number at two to three hundred. Certainly many people were ‘disappeared’, perhaps even a thousand in the five years after the massacre. I had been involved in the movement, operating an information cell. We would gather information on the rebellion, on the uprising, translate it into five languages and send it abroad clandestinely, through the mail system. When we realised that many of our close friends and associates were being picked up and arrested, my wife and I decided we had to leave the country. Seeking asylum, we arrived in England with our two little children (who are now fifty-two and fifty-one years old) and barely $200 between us. We had to report to the police every week for about a year. My kids are pretty swarthy and they suffered in London for it. We were living in a very down-and-out Islington. Now it’s a very posh area, but at that time it was really down and out. My boy got the shit kicked out of him. So we decided to leave London and settle down in Clyst Hydon, a hamlet just north of Exeter. That’s when everything started popping.

AR And that was where the Beau Geste Press was initiated?

FE Right. I had bought this duplicator in London. I suddenly felt I needed it, because a very close friend of ours had been arrested and sentenced to 14 years in jail for having used a mimeograph in Mexico, allegedly ‘for subversive reasons’, so for me, it was a very dangerous tool. That’s how I got into printing. In London I somehow met the poet Mike Gibbs, who lived in Devon and printed poetry. Through him I met David Mayor, who was taking an MA at Exeter University. At the time, he was studying under Mike Weaver at the American Arts Documentation Centre and that’s how I managed to gather this little group of artists, in the backwaters of Devon, and became part of the Fluxus network. We worked with people all over the globe, Ulises Carrión from Mexico, Claudio Bertoni and Cecilia Vicuña from Chile, Riyoo and Hiroko Koike and Yukio Tsuchiya from Japan, Kristjan Gudmundsson from Iceland… Brits like filmmaker Michael Leggett, writers Allen Fisher and Opal L. Nations, composer Michael Nyman (who now lives in Mexico) and many others. Art is about linking people up… no two ways around it.

This article was first published in the September 2014 issue.