The late and overlooked artist’s works, on view at Project Native Informant, London, present a disturbing vision for our morally and aesthetically puritanical era

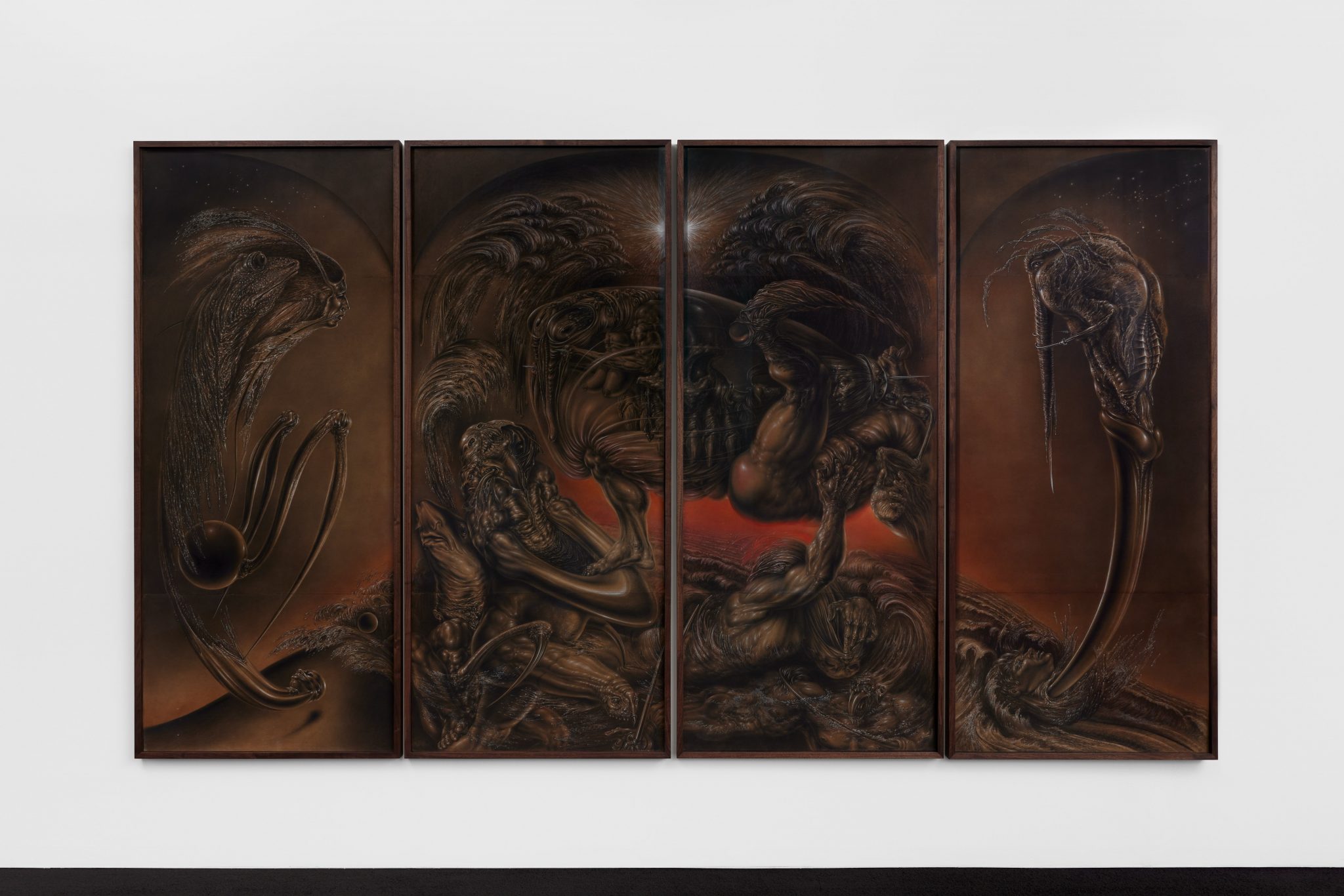

The floor of Project Native Informant is newly carpeted – black, thick, the pile giving under each step. It’s the most comfortable you get in Frenzy of the Visible, a first UK show of the late Sibylle Ruppert’s work, who dealt in drawings, paintings and collages of grisly, libidinous horror. Overlooked during her career, the German-Swiss artist only received a retrospective, at H.R. Giger’s private museum in Zürich, in 2010, the year before her death. In a four-panel work of Crayon and charcoal on paper, La Bible du Mal (Bible of Evil, 1978), muscular, bulbous figures in greys and browns tussle across the two middle panels, propped up by a clenched calf growing out of something like a beetle with small breasts; and a herculean arm grasping at what might be a body in foetal position or a penis with abs. Spouts of water frame the amorphous forms; sticky black droplets amid the white flecks look like eyes – hungrily, lustfully watching. On the far-left panel, the face of a frog is skewered to flesh emerging from a hollow, metallic-looking face, its mouth pinned back by a fishhook. Oh, there’s also a phallus with the face of a shark and, on the far-right panel, a hummingbird on steroids atop a tusk impaling a cherubic human head. Above it all, starlight shines white and clean, a halo awaiting a messiah. There’s something here of Hans Bellmer’s freakish, limby drawings and Max Ernst’s surreal painted nonplaces, as well as a Boschian sense of theatre to the framing. But Ruppert makes each feel prudish by comparison. Her works aren’t just evocative of nightmares, they’re inspiration for having even more disturbing ones.

In Ruppert’s universe, all is fair in sex and war. There are no morals to impart. The violence depicted is often unbearable but carried out with devilish zeal – in Ma Soeur mon Epouse (My Sister My Wife, 1975), a crow-beaked being plucks at the penis and feels for the nipples of an androgynous figure splayed on a bed, aided by conniving faces in the charcoal-drawn shadows. Our empathy, or whatever is left of it looking at this vision of abuse, is pulled towards the prone figure’s right hand grasping at gathered sheets. In La Fontaine (1977), a three-headed creature expels a half-formed person from, you guessed it, its outrageously disproportionate member. The person grasps at the air, their hair swept into a frenzy by vicious pencil strokes, then falling into a pristine pool of liquid beneath. We are all, Ruppert suggests, born violently into the world, then disappear back to it, returned not as beings but matter.

If ours is a morally and aesthetically puritanical era, Ruppert’s work is a tonic. Frenzy of the Visible would be horrifying if it wasn’t also such sickly fun. In a lithograph, La Langue (The Tongue, 1970), foamy snot runs down onto a pointed, lumpy tongue resting in a vulvic valley. An etching, Beilage zu Maldoror (1980), depicts a partially unfurled switchblade protruding from the torn crotch of an androgynous, again-muscular figure. Later collage works enter real-world objects into the equation: one figure has engines for lungs and metal-piping for bones (Untitled, 1981); leather kinkwear reveals ass cheeks joined to a bubbling torso in Pour l’Anniversaire de B.A. (1978). These point more determinedly to the queerness of Ruppert’s work, aesthetically evoking the occult sexuality of films like Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) and the Pop eroticism of Italian giallo cinema, and a female-gaze inversion of Giger’s nightmarish sci-fi – even if she never achieved their notoriety while alive. As a current cultural acceptance of a kind of nihilist transhumanism grows, Ruppert’s remarkable work – of a portentous, painful, fluid world – is perfectly, if belatedly, timed.

Frenzy of the Visible at Project Native Informant, London, through 20 April