“My reality seems like a made-up fantasy for some people. We are living in a world where many different realities coexist”

Sin Wai Kin first made a name for themselves onstage during the early 2010s as Victoria Sin, a drag persona that turned up the dial on Marilyn Monroe’s Old Hollywood glamour and the impossible physical proportions of blowup dolls. There were prosthetic breasts, custom-built corsets and a huge platinum blonde wig that “looks like it ate your wig for breakfast”, as the character snipes in Define Gender, a 2017 film portrait of the artist. The makeup was just as big: Pierrot-white face, exaggerated black-and-red mouth and fake eyelashes to sweep the floor with. It was a striking parody of the blonde bombshell. As Sin reflects during a visit to their studio, “Within capitalism, extreme representations are always going to be more successful because they’re unattainable, and more polarised representations of things like gender become normalised. Drag is a purposeful doing of that, which also undoes it.” It’s an argument implicit in the iconic trans performer and Monroe-obsessive Amanda Lepore’s claim that she has ‘the most expensive body on Earth’. “How Lepore literally blows [gender] up is very attractive to me,” says Sin. “Like, ‘You want me to do this? Here it is.’”

What gave Sin a critical edge in London’s more experimental drag nights was that the performer then identified as a ‘femme-presenting cis-girl’, as they once put it, a ‘female’ drag queen. As an outlier in a scene dominated by white gay men, their position turned the dial on what it means to knowingly put on a gender. For Sin, a Canadian of Cantonese descent, these initial forays were born of the need to explore their relationship with Western femininity. In the four short films that made up Narrative Reflections on Looking (2016–17), their graduate presentation at London’s Royal College of Art, the camera moves up and down Victoria Sin’s adorned and displayed body, which is as still as a poster pinup but for the artist’s visible breathing. Sin’s voiceover describes uncanny encounters with a teasing image of a woman who gazes back and looks just like the narrator – or nearly: “It was like looking into a mirror and finding that there was something missing in the reflection”. The speaker’s desire to consume the image has both a sexual and cannibalistic dimension, and this goes both ways. “I was eaten alive,” they purr.

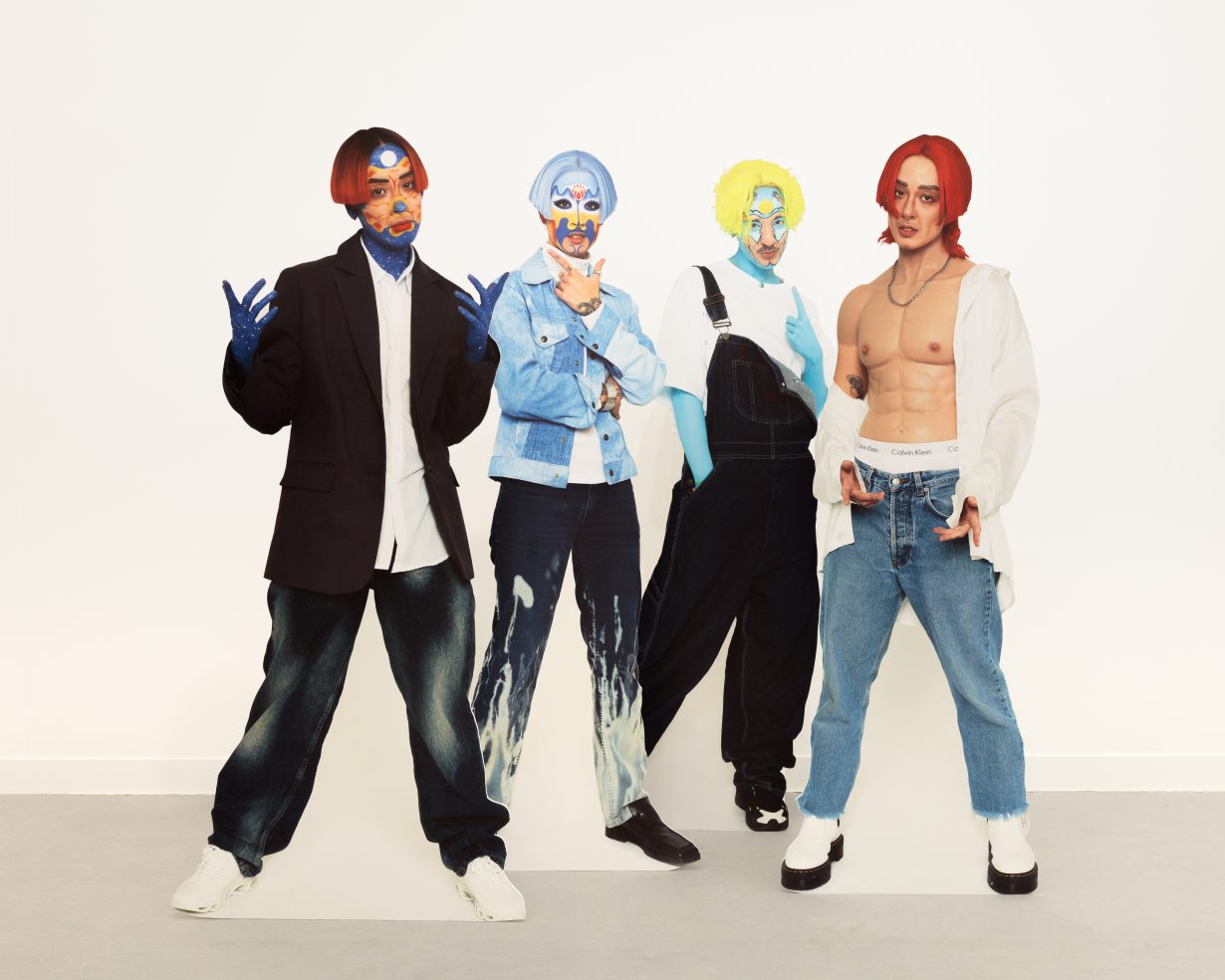

A sweep of the films and sculptures that make up Sin’s presentations in two current uk group exhibitions, this year’s Turner Prize and British Art Show 9, make clear that the artist’s vision has expanded considerably in recent years. The characters they play include members of a boyband who parade their literally singular qualities in a music-promo lineup and housewives with killer chopine platform shoes, bare fake breasts and Cantonese-opera face-paint. There’s an extraterrestrial newsreader who broadcasts a contradictory report from another galaxy and an Asian action hero who struts down a midnight street with a white fur draped off the shoulder. Steeped in personal history, Chinese culture and science fiction, their painted faces have moved beyond those of the early ‘gender clowns’. Sin’s voiceover – be it velveteen and girlish, or deeper with a synthetic ring – spins dreamlike scenes and poses probing questions through which binaries are set up and knocked down, be it male/female, fact/fiction or subject/object. In their universe, there’s even a dumpling that talks.

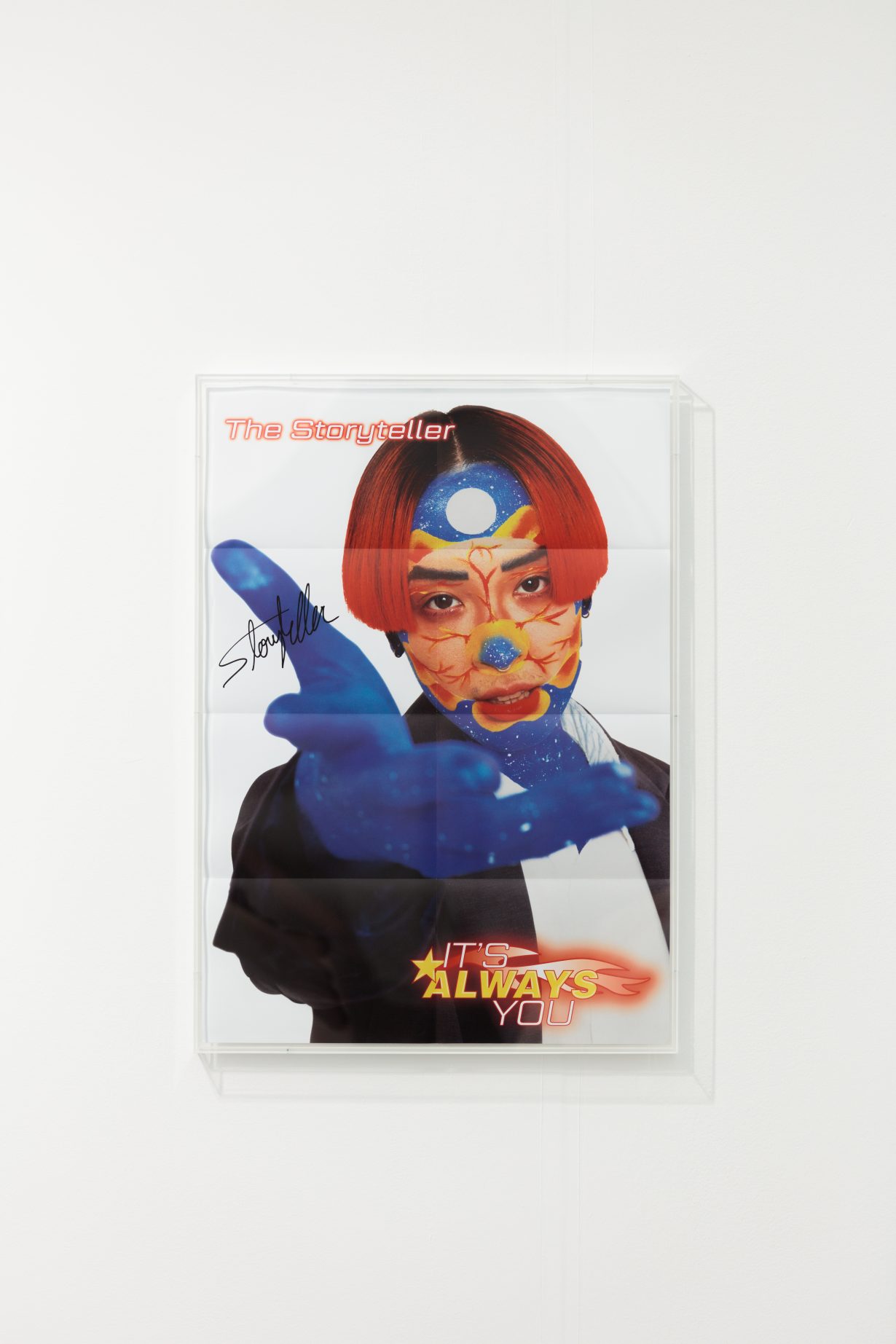

It was in 2020 that Sin’s project underwent some significant evolutions. Having cut their long hair into boyish curtains and reverted from Victoria to Wai Kin (their Chinese name), they created the first fully fledged masculine character to take an ongoing place in their work. With orange hair and makeup that channels cosmic symbols, including a blue starry sky, white moon and red flames, The Storyteller looks like a being from outer space. (It’s no surprise to hear that speculative-fiction writers Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler have made an impression on the artist.) Inspired by that traditionally male figure of supposed authority, the newsreader, in Today’s Top Stories (2020), the Storyteller’s report is structured around opposing statements concerning certain death and immortality, dreams and waking life, cohesion and separation, as unstable as the blue star imploding in the background. His bulletins include the severing of self and other through language: “in the telling there is a dividing”, he informs us. (A poststructuralist riff on ‘fake news’ perhaps?) The instability is underscored by references to Zhuangzi’s third-century thought experiment, Dream of the Butterfly, in which the Daoist philosopher questions if he is a man dreaming he’s a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he’s a man. “I identified with it in that my reality seems like a made up fantasy for some people,” says the artist. “We are living in a world where many different realities coexist.”

The Storyteller has since appeared in a number of Sin’s films, including their brilliantly creepy take on boybands’ off-the-peg appeal, It’s Always You (2021). Here, the character is ‘the serious one’ in a four-man lineup of reductive types (alongside the childish one, the heartthrob and the pretty boy), as flat as mirrors onto which their fans can direct their own reflection. The artist’s interest in the butterfly dream meanwhile has led to their longest and most ambitious work to date, A Dream of Wholeness in Parts (2021), a 23-minute film shot on location in Taiwan. In it, the narrator’s voice takes on the lulling tones of a sleep meditation, guiding the viewer/listener through seven scenes inspired by the artist’s dreams. There are two recurring characters with traditional roots. The Universe, with blue hair and floral face paint, draws on the warrior archetype from Cantonese opera, while The Construct corresponds to the female roles known as The Daan. Yet Sin strikes beyond the binaries of gender here, to shake up reality on a grand scale. The voiceover veers from descriptions of trees, moonlight on skin and food, to nightmarishly being cut in two by elevator doors and, more hopefully, the ruined landscape of one’s forebears that is left behind. The images with which this narration is paired do not necessarily match up. The meaning of a description of oily glistening broth and thin-skinned dumplings turns extra-slippery when set against a shot of a bare-breasted character with long black hair posing on a windy rocky beach strewn with flowers. With psychedelic verve, there are moments when a talking tree-trunk, chess-piece and wonton soup take over speaking the characters’ lines. It’s a ‘carrier bag’ fiction of the kind advocated by Le Guin, its components left to jostle side by side, free from the prescribed journey and conclusions more linear tales might force us to take.

Sin’s characters are category-hopping creatures of flux, donned for public appearances onstage or in front of a camera. Yet the artist has also found a way to memorialise the fleeting personas using a material ubiquitous in drag-club dressing rooms: the face wipe. Putting the emphasis on the ‘taking off’ as much as the ‘putting on’ of a persona, these works preserve the made-up faces on tissue, along with the sweat and skin cells mortal bodies shed beneath the paint. The face prints make us think about the ‘self ’ underneath the fabrication, yet Sin exposes this perceived division between performer and role as another binary to be dismantled. After it was cut, the artist also turned the long black hair that had signified their ‘authentic identity’ offstage into a wig. It’s worn by The Construct and can be seen IRL in the Turner Prize exhibition. The title says it all: Costume for Dreaming (2021).

Work by Sin Wai Kin can be seen in the Turner Prize exhibition, Tate Liverpool, through 19 March and as part of British Art Show 9, various venues, Plymouth, through 23 December; a new film, The Story Cycle (2022), can be streamed on the Somerset House’s website