Snare for Birds at Ateneo Art Gallery, Manila revisits imperial and colonial narratives from the American occupation of the Philippines

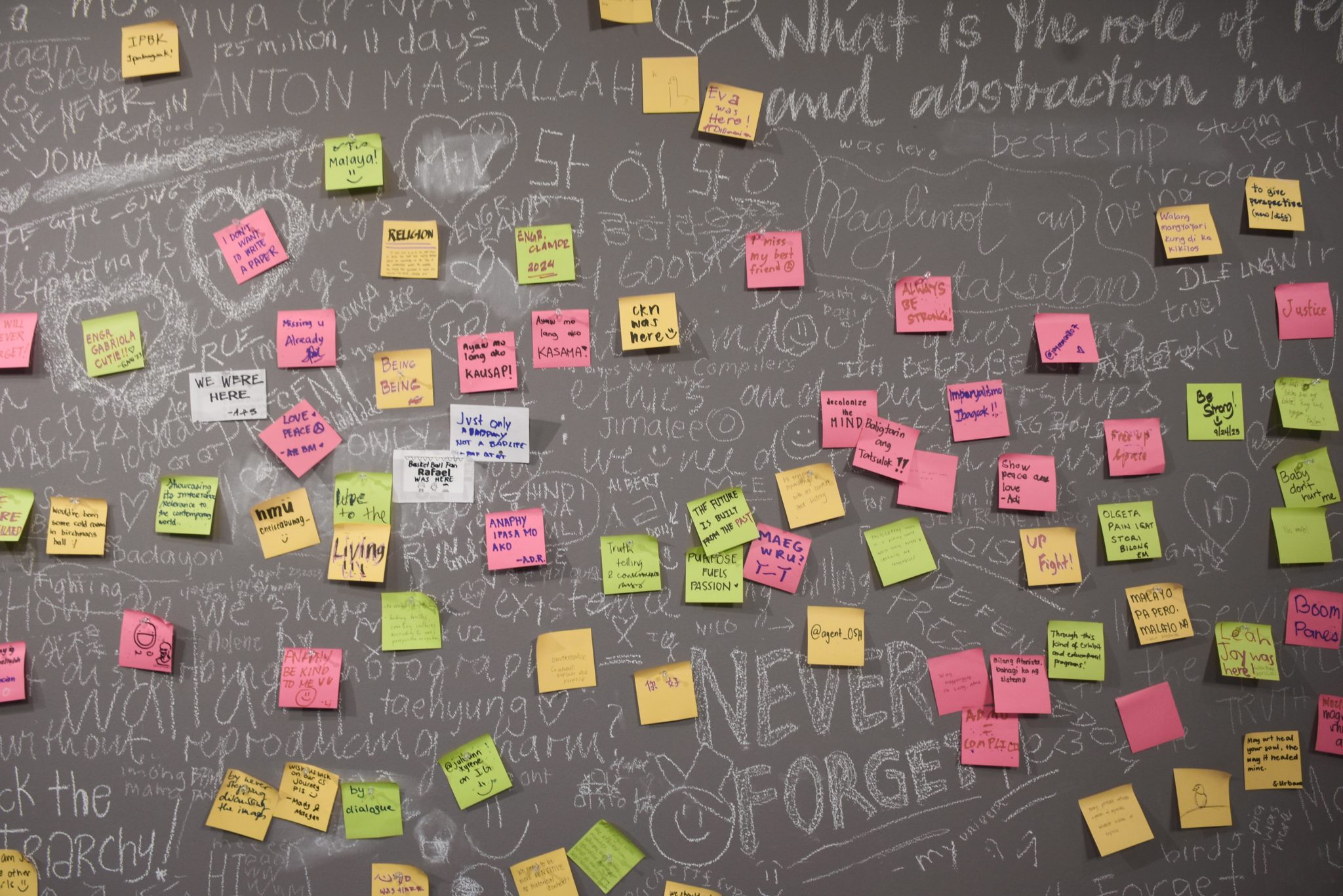

Since 2020, artists Kiri Dalena, Lizza May David and Jaclyn Reyes have been collaboratively researching the imperial and colonial narratives from the American occupation of the Philippines – a process that was presented as benevolent assimilation, and resistance against it as insurrection by bandits. This group exhibition delves into European and American archives and various historical texts to grapple with obscure stories of violent personal experiences, with dense and layered works evoking unresolved stories and deeply felt responses.

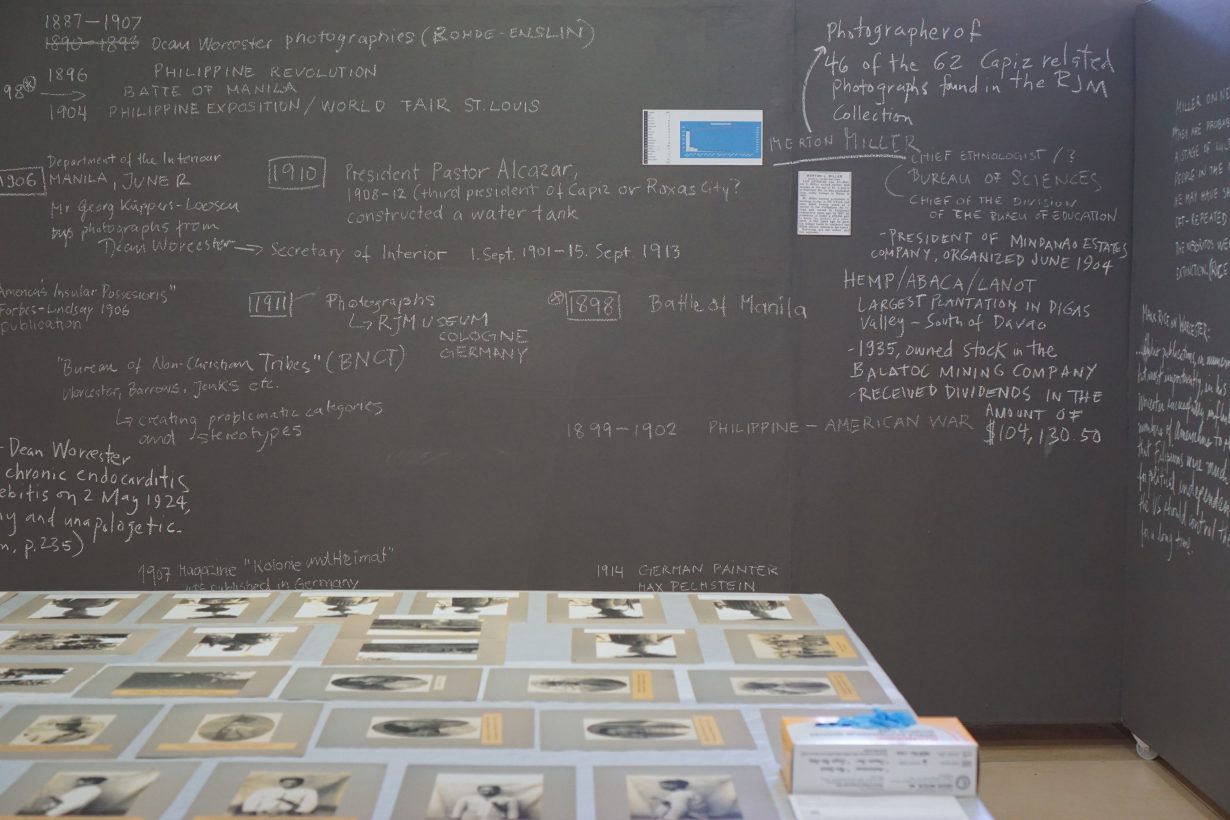

Central to the exhibition are three videoworks by Dalena that use research from the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum’s collection in Cologne and translations of the 1908 editorial ‘Aves de Rapiña’ (Birds of Prey) published in the bilingual Spanish-Tagalog newspaper El Renacimiento. Two projected videoworks in the loop – Mga Ibong Mandaragit (Birds of Prey, 2023) and Birds of Prey (2023) – narrate the editorial in their respective titular languages over a series of archival photos of the Philippine countryside that were ubiquitous during American colonisation. The photographs highlight rough landscapes as just one part of the Philippines’ varied topography, often framing the country as raw and underdeveloped with unkept grasslands, trees and bushes. Towns and cities, even thriving farmlands, are often absent in such photographic representation. The purposeful depiction of sparseness and lack of built infrastructure – rather than a fuller picture of diverse terrains including natural land and waterscapes, as well as marketplaces, Spanish colonial stone architecture and local architecture utilising natural materials – strengthened the colonial narrative of the Philippines as a ‘white man’s burden’ that required American presence.

In contrast to these is Raubvögel (Birds of Prey, 2023), which uses contemporary moving images depicting aerial views of lush tree-scapes and birds flying in and out with German narration and English subtitles of again the same article, ‘Aves de Rapiña’. Though visually beautiful, the use of German language, here and in the subtitles of Mga Ibong Mandaragit, feels out of place. Many of the archival photographs Dalena uses were from a research residency with the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum, which explains the presence of German; but unlike Filipino, the national language of the Philippines, and English, the colonial language (and now also an official language), German fails to form a direct connection with the postcolonial narratives of the exhibition.

‘Aves de Rapiña’, referenced in these three videoworks by Dalena and looping on a single projector, is a critical text in representing the censorship and oppression of American colonisation despite the appearances of benevolent peace. The editorial alludes to Dean Worcester – then Secretary of the Interior in the colonial administration and a fierce advocate for colonialism – with references to his work as an ornithologist and suggests he used this as a cover to exploit Philippine resources for personal gain. The American sued for libel and won. The resulting fines led to the closure of El Renacimiento, while Worcester’s writings and photographs (some of which went to the Rautenstrauch-Joest) became definitive in forming Filipino imagery and identity during this period. Dalena’s videoworks are not simply about the injustice of colonisation; more importantly they quietly highlight the continuing inequity in narratives of history.

Jaclyn Reyes also utilises colonial photography, focusing on portraiture and engaging with how these depictions leave their Filipino subjects unnamed despite putting effort towards identifying the photographers and publishers that thereby sustain American colonisation through the archive. Often leaving the name and story of the photographic subject unknown, the archival process implicitly places more value on the colonisers who were behind the lens and production processes. The United States’ Library of Congress holds many of these photographs, including Filipino prisoners of war at Pasig, Philippine Islands (c. 1899), published by Strohmeyer & Wyman with the copyright claimed by Underwood & Underwood. In a bid to reframe the archival photo, Reyes draws the subjects of this image: Untitled (2020) is a charcoal portrait of the two persons standing in the upper-right-most frame of the photograph. She refers to her approach as ‘Drawing Portraiture as a Research Methodology’ in a selection of printed supplementary materials accompanying the exhibition, employing the hand-drawn form as an attempt to slow down the process of looking and supposedly redignifying the subject of the photograph. Though the intentions are sincere, the transfer of power in the representation remains elusive – the full context is still missing, and the subjects’ voices remain silent.

Snare for Birds: Rereading the Colonial Archive at Ateneo Art Gallery, Manila, through 17 February