At Lisson Gallery, London, the artist returns repeatedly to the relationship between words and colour, language and landscape

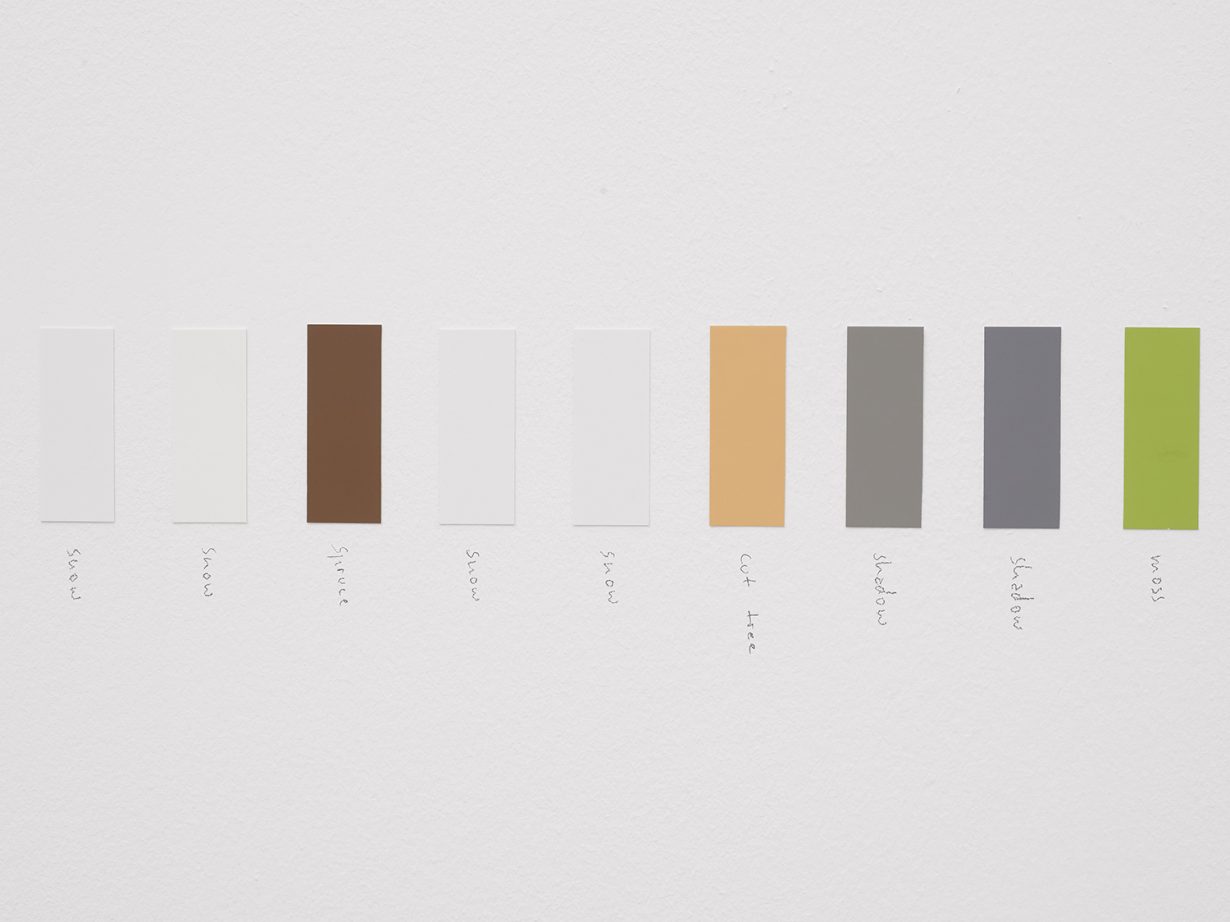

The first work visible upon entering Spencer Finch’s latest exhibition appears as a line of narrow coloured rectangles running along the left and rear gallery walls. Upon closer inspection, they reveal themselves to be paint swatches, each accompanied by a description written in pencil below: ‘trail sign’, ‘trail’, ‘spruce’, ‘sky’. Following the line of swatches, you repeat Finch’s journey along the route named in the work’s title: Crawford Path up Mt. Pierce, New Hampshire (after a spring snowstorm) (all works 2021). The colours are those identified by Finch as corresponding to things seen on his hike; corresponding being the key word, since the colours are in fact those available in the Benjamin Moore paint catalogue. An individual’s perception of colour is mapped by readymade industrial categories; a continuous experience divided into a linear grid.

Finch calls this work a ‘a peculiar kind of landscape painting’, one that came from ‘marvelling at the range of colours that arise out of this seemingly monochrome material’. Yet marvel isn’t exactly the mood this work conjures, captivating as it is. In foregrounding the way our encounters with nature are mediated by industrial technology, it evokes and shares the historical conditions that led to the emergence of landscape painting: the artist’s sense of alienation from the natural world that made the object appear as a discrete subject to be painted, rather than part of a more general environment in which one belongs. The somewhat melancholy tone accompanying this work is heightened by those sections where the same word, ‘snow’ or ‘shadow’, appears multiple times beneath seven or eight different coloured swatches. It is a reminder of the poverty of the English language – of many languages – when faced with the variety of the natural world.

Other works in the exhibition return again and again to the relationship between words and colour, language and nature. Cloud (cumulus fractus under stratus, Connecticut) consists of an image of a cloud, painstakingly composed out of layers of Scotch tape on grey board, accompanied by the label that forms the work’s title. The image aspires to depict a particular formation, language works to classify it into a group. A series entitled Fresh Snow (morning effect) consists of flecks of silver leaf on white paper; the painstaking effort of depicting a particular appearance contrasting with the generic similarity of the titles.

Almost turning to the exoticising cliché of the Inuit having a hundred words for snow, a set of works occupying a single room are named after usuyuki, a Japanese word meaning ‘thin snow’ or ‘light snow’, suggesting that other cultures, by being closer to nature, have retained a linguistic diversity, or even a kind of projected primitivism, lost to those deadened by civilisation. These works consist of layers of white tulle suspended from rods on the gallery wall. Perhaps because – titles aside – they feature no words, or conceptual mediations on language, these works are the most successful in drawing attention to the visual complexity subsumed in colour words like ‘white’. Shade, density, luminosity and intensity shift as you spend time moving around the gallery, or as a weak sun comes and goes on a characteristically disappointing English summer’s morning. Evoking the techniques of Light and Space artists like Mary Corse, this room enables you to understand that our experience of colour is not predetermined, or readymade, but shaped by context and time, always in flux.

A final room, housing Mistakes I, another series of coloured squares running along the gallery walls, suggests that our failures to perceive the world correctly have been Finch’s theme all along. Each coloured square of card contains a pastel smudge and pencil description: ‘a wave mistaken for a duck’, ‘wet leaf mistaken for dog poop’. The overall tone is one of humour, as if to encourage us to laugh at how we will always get it wrong. If this is a welcome deflation of a ponderous seriousness that can sink many works in the tradition of Conceptual art that explore the relationship between ‘Art and Language’ – to name but one artistic project that takes these questions very seriously indeed – the room does lower the stakes of the exhibition somewhat. Words don’t match the world, perception is always deception. What does it matter, if it is all just a joke?

Spencer Finch, Only the hand that erases writes the true thing, Lisson Gallery, London, 22 June – 31 July