A first US solo exhibition surveys the Japanese photographer, often overshadowed by male counterparts she assisted such as Daidō Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira

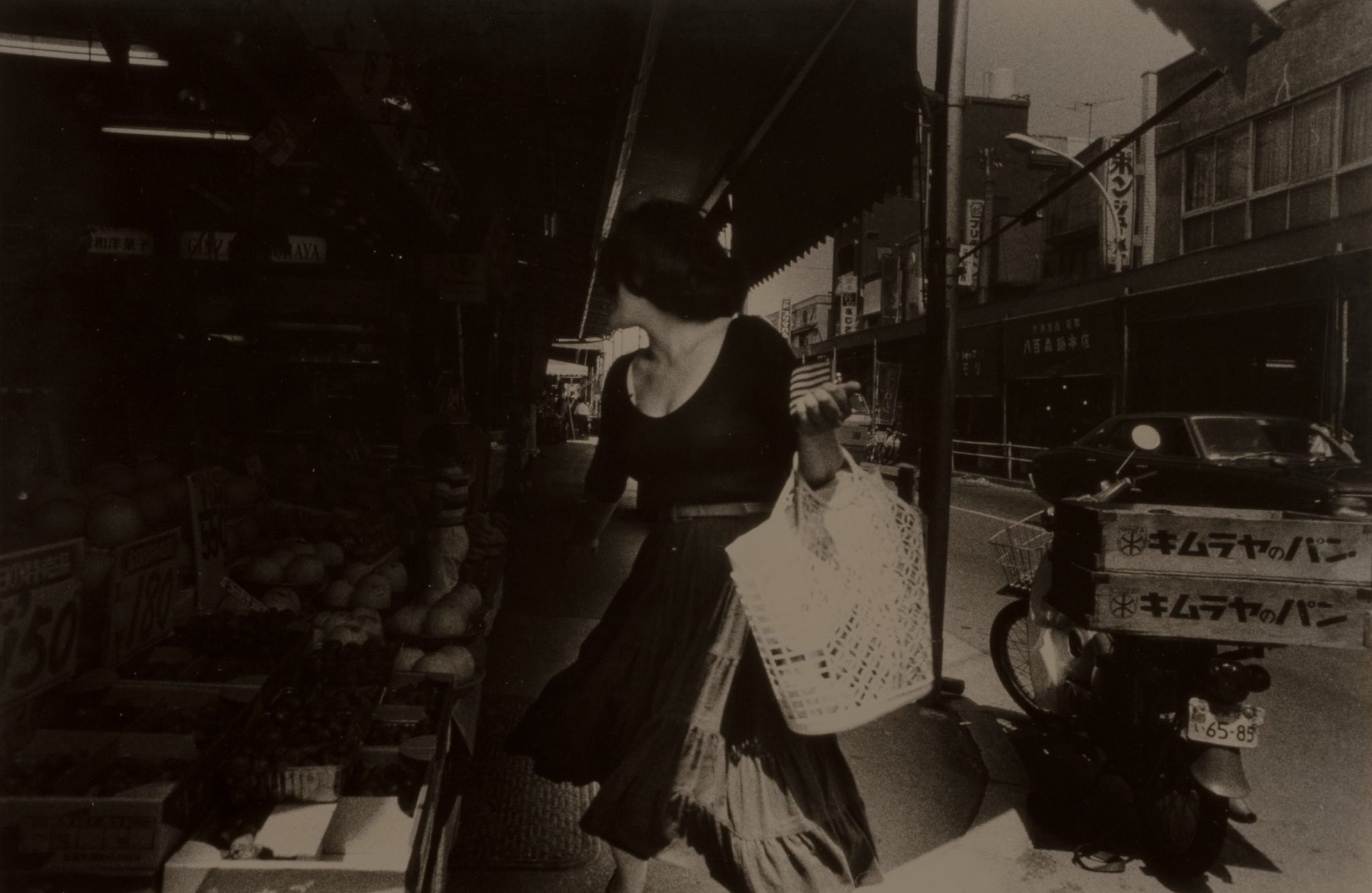

Few legible faces appear in the grainy black-and-white photographs of Tamiko Nishimura. The subjects in Journeys, her first US solo exhibition – mostly women, captured in quotidian moments – tend to escape the camera’s gaze. Most of them turn away from us. Some are simply silhouettes. The faces we do see are often partitioned, obscured: in Eternal Chase – Hakodate, Hokkaido (1970–72), a cloche hat covers the eyes of a young citywalker; in a garden in Shikishima — Okunakayama, Iwate Pref. (#016) (1972), a mother burrows her nose into her baby’s hair. And then, in other photographs, there are the visages rendered so faintly as to appear spectral: an infant peeking over her mother’s shoulder at the beach; a woman trudging up a snowy hill. Even Nishimura’s most sensual portraits, like those in her 1970 series Kittenish…, contain only closeups of bent knees, splayed thighs, languid hands.

Nishimura, who was born in Tokyo in 1948, is often overshadowed by male counterparts such as Daidō Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira, both of whom she assisted in the darkroom as she began developing her own images at higher temperatures and with longer exposures. The photographs on display in Journeys – largely taken between 1969 and 1978, spanning six series and displayed as gelatin silver prints – typify the subversive style she found through these darkroom experiments: granular and high-contrast; understated, spontaneous and subtly haunting. Her images evoke hazy memories – just barely out of focus, and out of reach. Taken together, her unidentifiable women become half-recalled figures, the particulars of their faces the casualties of time. Yet in simulating the tenuousness of memory, Nishimura firmly immortalises her subjects.

Nishimura’s practice was facilitated by her peripatetic lifestyle. During the 1970s, at the start of the Japanese women’s liberation movement, she travelled throughout Japan, photographing scenes of impermanence across its distinct geographies, from the dark, foamy waters of the Tsugaru Strait to the still, snow-coated tableaux of Kodomari and Ōmagari (both towns would later be redistricted out of existence). A quintessential flâneuse, she also found quiet enchantment in unpeopled urban landscapes, which she captures with her signature fuzzy, memory-warped tone: the shadow of a utility pole in Osaka; a leggy mural in Kanagawa; gently sloping trolley tracks in Hokkaido. Each photograph here is a tacitly feminist ode to her own freedom of movement. One can picture the twenty-something photographer, clutching her camera, alone and alert to the world. One can also picture a seventy-something Nishimura doing the same: the most recent work in the exhibition – an exultant portrait of a firework display titled My Journey III — Tokorozawa, Saitama Pref. – is from 2022.

Despite the poignancy of her landscape photography, Nishimura’s faceless, city-dwelling women are her most indelible subjects. This is especially true of the women she photographs in Tokyo: the stylish grocery shopper at an outdoor produce stand, mid-step and turned away, her skirt swirling around her as a bag dangles from her forearm; a pair of sandaled women walking swiftly down a sun-dappled sidewalk, their backs to us. In these images – tender, candid and shot through with empathy – women refuse to pose for the camera. Or they simply don’t see it: their obscured faces, more than just an aesthetic conceit, suggest they are too preoccupied to be bothered. Tracking them with her subtly feminist gaze, Nishimura captured the fullness of their lives in a way that feels just as fresh today as it did half a century ago.

Journeys at Alison Bradley Projects, New York, through 29 June