At Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, the artist’s first major solo show is a study of what it means to maintain a sense of self

After graduating from Warsaw’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1971, Teresa Gierzyńska exhibited only intermittently over the ensuing decades, during which she was married to painter Edward Dwurnik – with whom she had a daughter in 1979 – before divorcing him after 37 years. But she maintained her practice throughout and acquired a quiet following. While her husband commanded the studio and public sphere, she was staging and developing photographic artworks in cramped bathrooms and shadowy bedrooms, interrogating the border between the body and its environs, and also that between the artist couple: in one photograph from 1980, a hand (presumably her husband’s) writes ‘Dwurnik’s’ (also the work’s title) on her sun-scorched back (her lily-white bum in contrast seems a deliberately droll yet affecting inclusion). Significantly, the title of her first major solo show, Women Live for Love, is a quote from cultural theorist Lauren Berlant, who finished the sentence with ‘and love is the gift that keeps on taking’. Gierzyńska’s oeuvre is a study of that condition and what it means to maintain a sense of self throughout.

The dimensions of the works exhibited rarely exceed the limitations of domestic space. The majority of them come from Gierzyńska’s autobiographical series About Her, which she has worked on since her graduation to the present day, the third-person title suggesting Gierzyńska’s ‘I’ cannot disassociate from the objective ‘Her’. These are shown in conjunction with transfer prints from The Essence of Things and the Notepad series of the 1970s, in which she extracts and collages imagery from German women’s magazines. Sometimes employing Xerox, or a dusty plaster surface to ground her images, the results are almost archaeological, and the kineticism contained within her surfaces suggests a story that is mysterious yet refuses to lie dormant. Joanna Kordjak’s curating sensitively focuses the essential qualities of Gierzyńska’s work, and the display has an airiness that adroitly compensates for years of confinement, dispersed in a quiet yet emphatic exhalation through three grand rooms of Zachęta. There is also wistfulness. This is one of the last exhibitions under director Hanna Wróblewska, soon to be supplanted by a stooge of the nationalist-populist government in its brazen attempt to hijack the agendas of the nation’s museums.

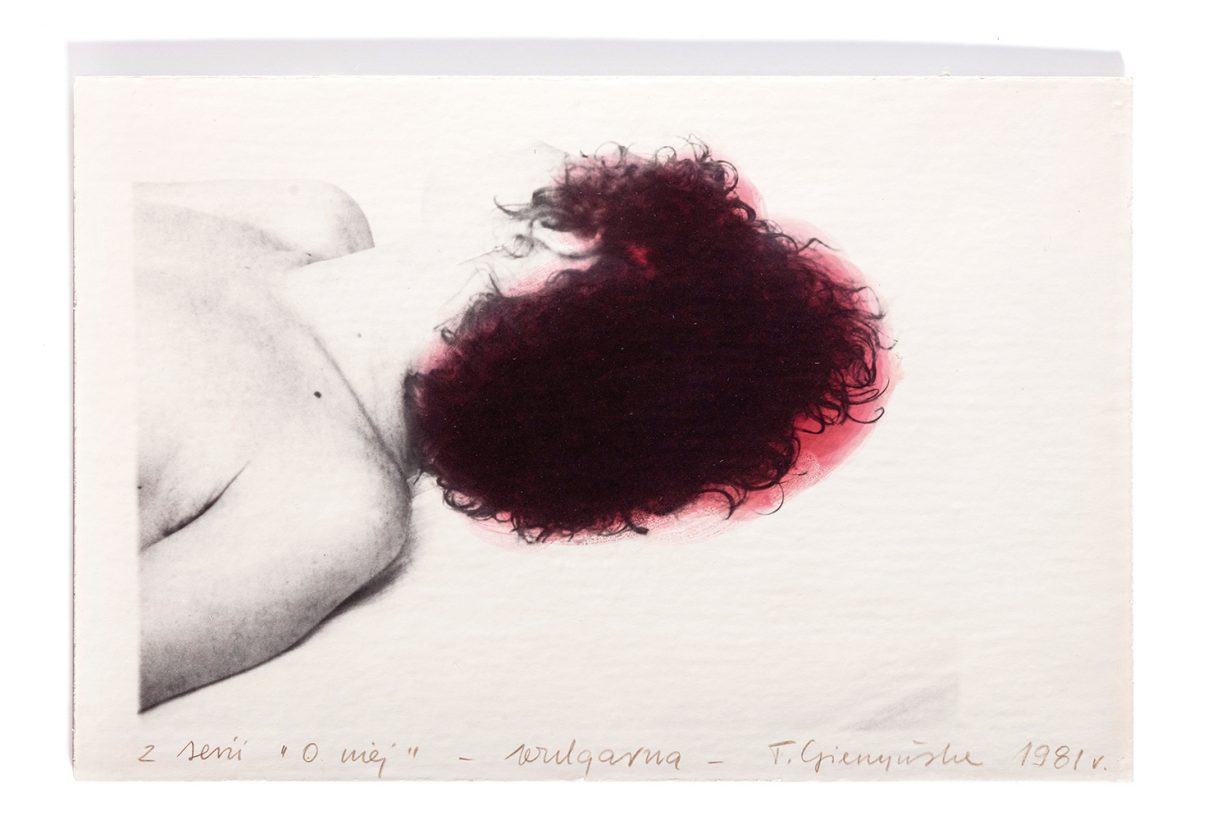

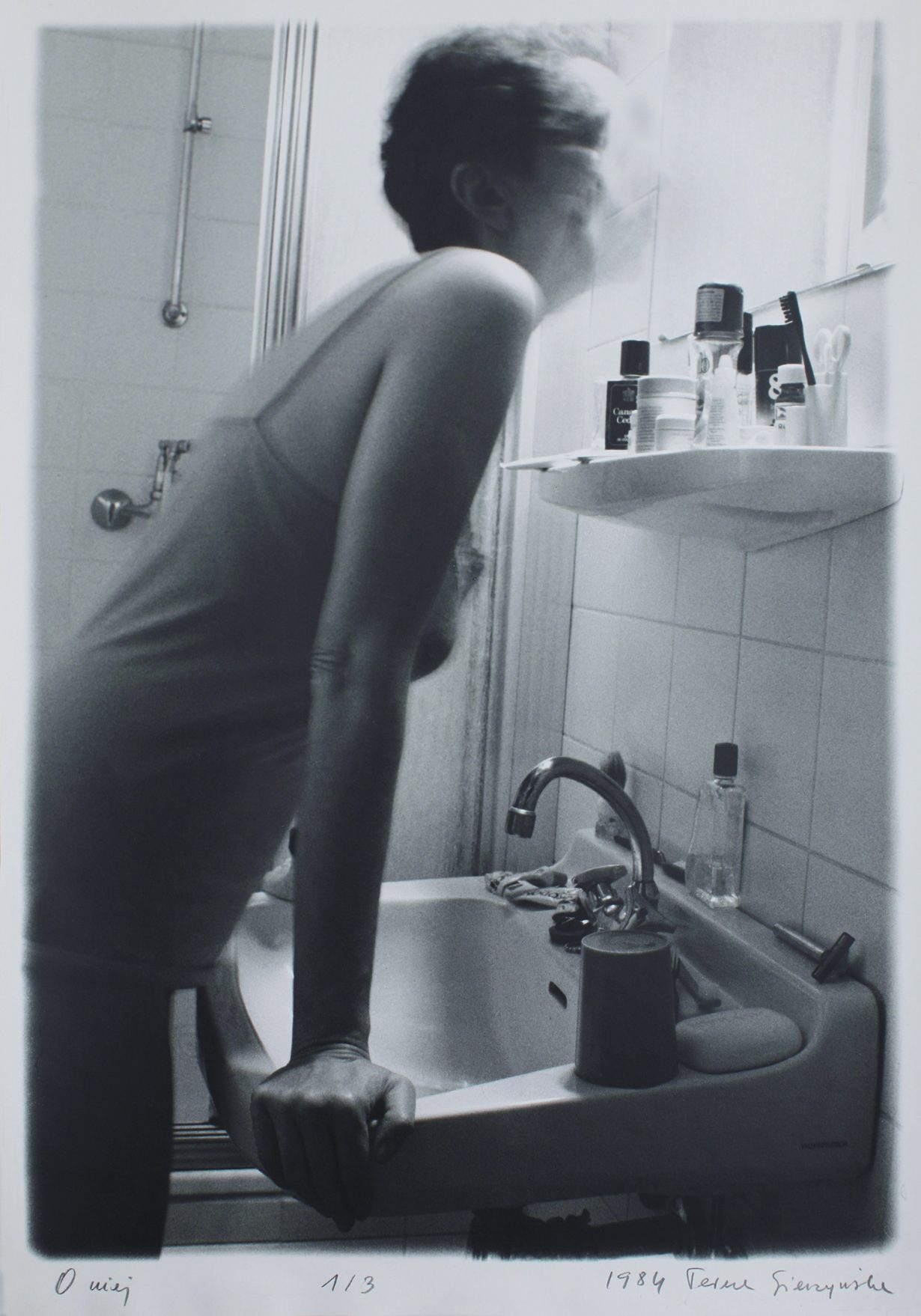

Only a handful of photographic works encircle the first room, the distances between them intensifying a sense of challenge and exchange. This mood and these works key the viewer into Gierzyńska’s world. One image shows a head turned away (surely a self-portrait, though the figure is cropped across the breast, their sex ambivalent), reclining on a surface that, as is common in Gierzyńska’s photographs, evaporates into blankness. The figure is cramped in the top-left diagonal of the picture plane, but their unruly mass of dark hair floods the centre. The artist’s familiar technique of applying colour to monochrome is here concentrated on the hair, tinted in aniline. A red hue bleeds out through the hooklike curls at the edge of this ‘black hole’ and, contrasted against white, recalls Poland’s national colours. The picture’s disquieting title is inscribed along the picture’s bottom edge in Gierzyńska’s fleet hand; ‘wulgarna’ – Vulgar (1981). Her titles, sometimes accompanied by a ‘studio stamp’ of a striding naked woman (inspired by Marina Abramović in her and Ulay’s 1976 performance Relation in Space), are as piercing as the decorative pin being pressed into a fleshy buttock in Caresses IX (1980). Revisiting and altering her approach to the same scenes, Gierzyńska conveys something of the claustrophobia, surveillance and obsession of the sociopolitical contexts in which she has worked, as well as her experience of the female condition, but ‘the world’ is only directly referenced through minor details, such as toiletries in a bathroom where the figure is a blur.

Another image from the first room augurs a different aspect of Gierzyńska’s terrain. In the Window (1984) shows a woman from behind, at a large window, hands on hips as she looks out into a sunlit clearing between the forest that darkly surrounds her field of vision. A dazzling blade of net curtain to the right side of the picture could have just been drawn back yet threatens to shift across and erase the whole scene. The figure’s reflection in the window becomes equally haunting as a pale blue tint subtly separates it from the monochrome whole.

Complementing Zachęta’s exhibition, Warsaw’s Gunia Nowik Gallery (which represents Gierzyńska) is exhibiting another version of this image alongside a cloudlike arrangement of rural scenes from 1984 to 1993, capturing, as the titles read, Thaws, Muck and Wind. Gierzyńska’s hypervigilance to ‘the outdoors’ is by no means the flipside to her more bounded environments, and here the tinted prints suggest a synaesthetic relationship to the furtive countryside of Central Europe. These thrumming vistas, a cascade of jewels or the colour-warps of a migraine, are best described by one title in particular: Anxiety.

Teresa Gierzyńska, Women Live for Love

Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 9 December – 6 March