How the artist’s radical vulnerability reverberates through art, literature and cinema

In Edvard Munch’s House in Moonlight (1893-95), a man in a hat has come to meet a woman in a white apron: his shadow falls at the woman’s feet; hers is folded like a jacket over the stone wall, her face and upper body obscured. Dark and disorderly greenery shrouds the house in secrecy. Two voyeuristic windows keep watch from above. She lingers by her gate, which remains on the latch – at least for now.

Munch, the subject of a new show at the Courtauld Gallery in London, has a knack for narrating in his art those moments that define our lives: youth, falling in (and out of) love, growing old, loss. He was 21 when he first met Millie Thaulow, wife of the artist’s distant cousin, Claus. The affair lasted two years, during which the couple would get together in the woods near the fishing town of Åsgårdstrand. When Millie called things off Munch was traumatised; the painting came almost a decade later.

A number of artists and writers have shared an affinity with Munch. In the 1974 docudrama Edvard Munch, the British film director Peter Watkins attempted to render his hypnotic vision in cinematic form, despite the artist’s claim that the camera ‘cannot compete with brush and palette – as long as it cannot be used in Heaven and Hell’. Frequent cuts and flashbacks reproduce Munch’s restlessness and manic mind, while extended shots of him choosing his materials and fixing his canvases show something else: discipline. Together with detailed sound design that amplifies his scratching brush marks, the whole lot draws attention to the technical process behind the seemingly frictionless transition of feeling to finished work.

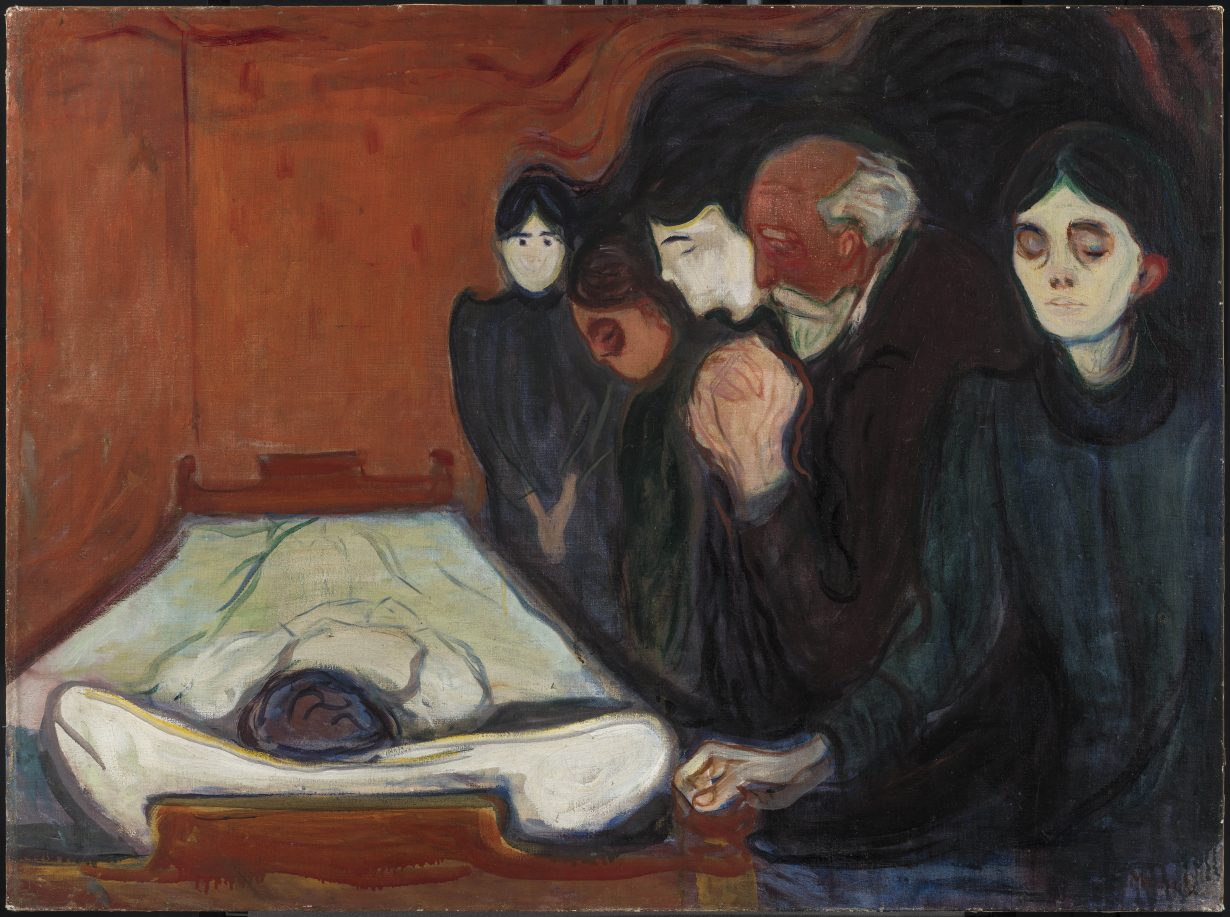

‘Disease, insanity and death were the black angels that stood by my cradle’, Munch wrote of his childhood. His mother died when he was five; his beloved sister, Sophie, in his early teens. At the Deathbed (1895), part of the agonising Frieze of Life paintings of the 1890s, shows Sophie swathed in white sheets and beside her a dim huddle of grieving figures in deep shadow. In The Beguiled (2017), Sofia Coppola takes that image and turns it on its head, giving us instead a handsome, wounded soldier propped up in bed in a girls’ boarding school, surrounded by giddy young ladies in pink and cream dresses made from satin and silk. Both painting and film are infused with stillness, a languid disposition.

Leo Tolstoy explores a Munch-like human landscape: pangs of youth, marriage, adultery, death. In Anna Karenina (1878), when Vronsky first catches sight of Anna while meeting his mother at a Moscow train station, Tolstoy evokes with words the kind of swell of emotion that the artist evokes with colour. ‘In that brief look Vronsky had time to notice the suppressed eagerness which played over her face’, he writes. ‘It was as though her nature were so brimming over with something that against her will it showed itself now in the flash of her eyes, and now in her smile.’ Maybe it’s too much to suggest that, if we were to swap out a few words here and there, he could be describing The Scream (1895) – absent from the Courtauld. The artist’s best-known work also depicts the bubbling over of an emotion – in this case, ‘a touch of melancholy’ – that started off gently simmering beneath the skin.

From one literary giant to another: Munch’s Summer Night, Inger on the Beach (1889) is an Emily Brontë-esque lesson in letting the natural landscape lead. In the same way that the wild and stormy Heath reflects the inner turmoil of Cathy and Heathcliff, the giant boulders of Munch’s shoreline give weight to his youngest sister’s feelings. Elsewhere, in a novelistic grasp, he captures on a single canvas the broad brush of life itself: the monumental Woman in Three Stages (1894) presents three imagined women signifying the progression from youth to maturity to old age, and beside them a sombre man, our anxious artist. Whether depicted in a dream-like setting or on an ordinary street, his painted lifecycles hum with deterioration and sunken dreams.

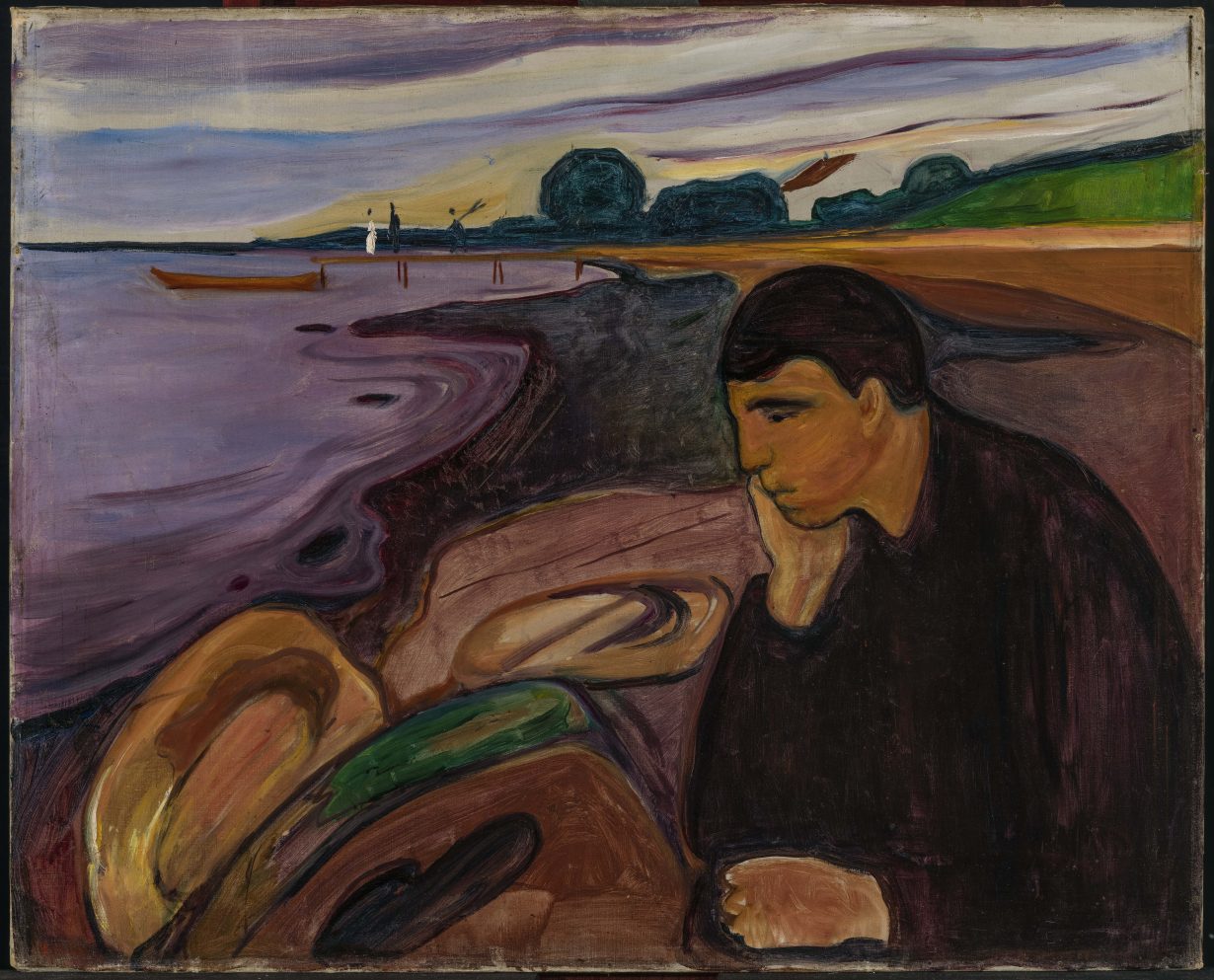

Like a capable cinematographer, Munch can seamlessly switch between backdrop and figures, panorama and close-up. At times he gives a glimpse of narrative, as in Moonlight on the Beach (1892), with a lone boat on an otherwise empty seashore, and in Melancholy (1984-96), which shows a man with his head in his hand and, on a jetty in the distance, a couple talking. Tracey Emin, who, in her own words, has been in love with the artist since she was 18, produced Homage to Edvard Munch and All My Dead Children (1998). Shot on Super 8, the single-channel video records Emin doubled over on another jetty in Åsgårdstrand letting out a piercing cry. She takes the radical vulnerability of Munch and turns it up a notch, with gut-wrenching drawings and films that are harsher, louder.

All this is to say that, like a writer who puts into words thoughts and feelings that we’re familiar with but fail to articulate, Munch visualises both the big and small moments that make a life. Morning (1884) – one of his first major paintings – shows a young woman, probably a housemaid judging by her modest clothing, perched on a bed, dressing or undressing. Daylight filters through the room and she turns towards the window, a silvery highlight tracing her nose. What’s she thinking? She’s missing a sock and her blouse is unbuttoned. Could the growing light reflect a realisation or resolve?

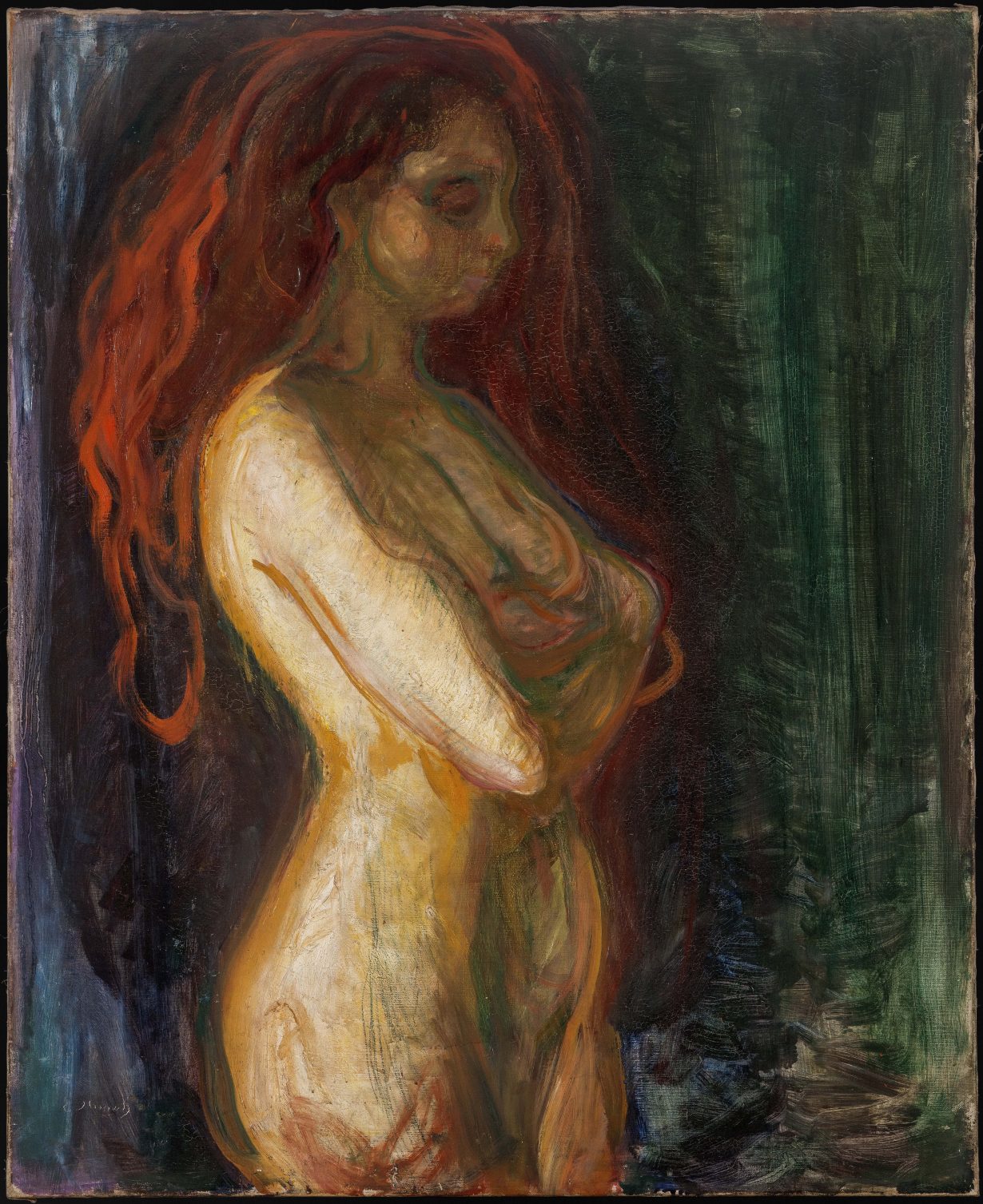

In the exhibition’s final room hangs Nude in Profile Towards the Right (1898). The narrative has been lifted directly from literature, in this case the Bible. Here’s Eve, arms tightly folded in front of her bare chest, eyes downcast, chin dipped. Painted against a gloomy blue-green background, her flesh blazes a bronzy gold – burning with shame as she’s driven from the Garden of Eden. But then standing before us is also a self-conscious young woman, painfully aware of our gaze. We could see Munch’s paintings as a series of mirrors held up to the world he lived in – a group biography of sorts – or a collective portrait of the artist himself. Stand once again in front of House in Moonlight, though, and for a second you’ll wonder if the shadow stretching out across the grass is yours.