Uncovering the life and books of a long-ignored, often publicly derided author who forged edition numbers, self-penned reviews and installed sympathetic audiences

In the opening section of this book, art historian Michael Sanchez relays the often-repeated anecdote of the teenage Roussel’s ecstatic vision of a theophany as he wrote his first novel, La Doublure (The Understudy, 1897), in which the young writer was suddenly surrounded by rays of light that emanated from his pen, and concluded, ‘Doubtless, when the book was published, this dazzling blaze would be revealed even more and light up the entire universe’. The encounter assured the fledgling writer of his own predestined renown.

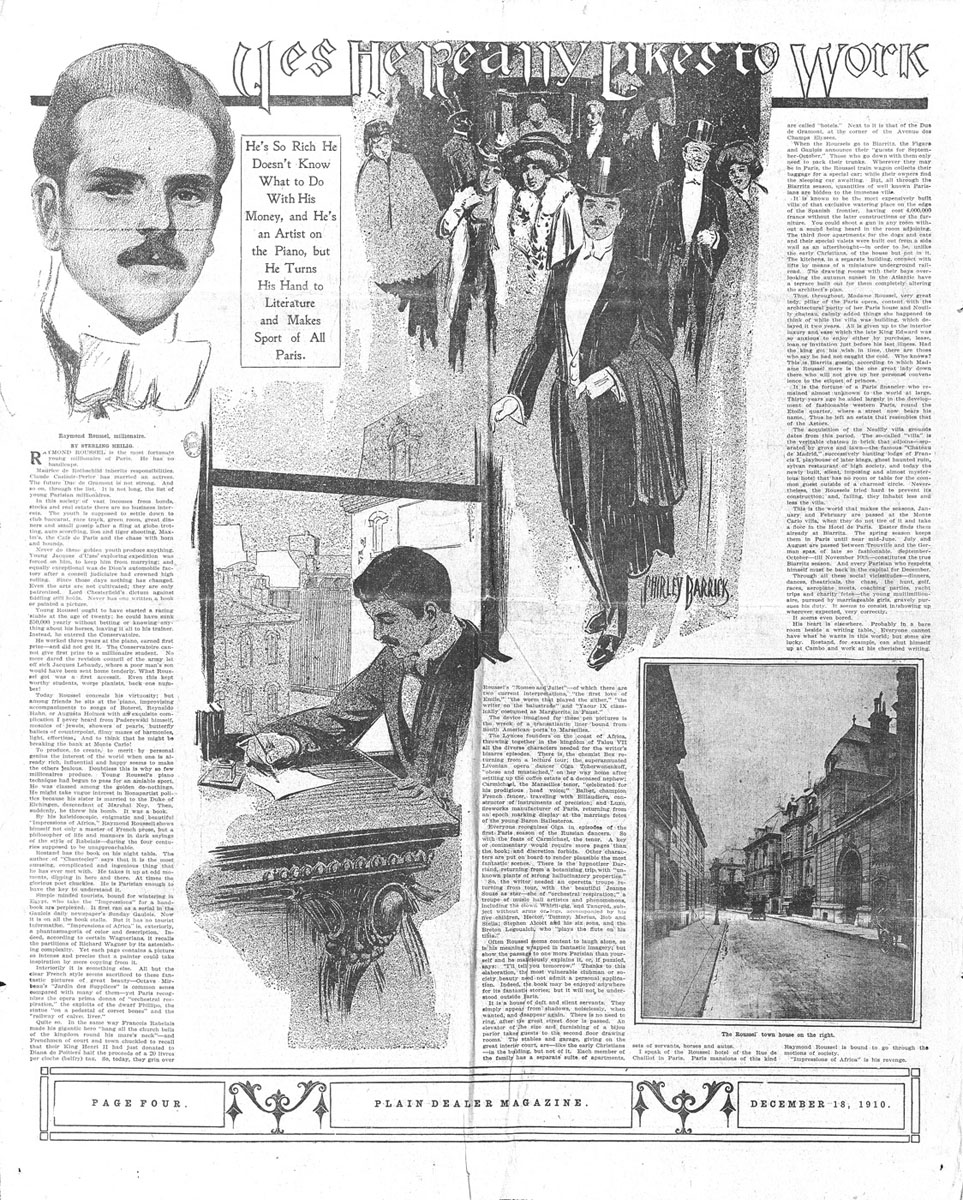

But recognition of Roussel’s genius was never to materialise, not in La Doublure nor any of his subsequent novels, poems, theatrical adaptations and fanciful inventions, which were ignored or roundly derided by the public during his lifetime. Again and again, Roussel’s baroque novels like Chiquenaude (1900), Impressions d’Afrique (1909) and Locus Solus (1913) baffled their readers. His long-term depression (and eventual suicide) was itself so grandiloquent that he served as a case study in French psychoanalyst Pierre Janet’s landmark text De l’Angoisse à l’Extase (From Agony to Ecstasy, 1926). It was Janet who, in diagnosing Roussel as a melancholic with delusions of persecution, wrote: ‘[his] life was constructed like his books’, an apt but disturbing analogy of Roussel’s increasingly theatrical renditions of reality.

Sanchez lays out his account accordingly, examining Roussel’s oeuvre and personal history, with a strong curatorial emphasis on the publishing history and adaptations of each text. (The Books and Life… was released in tandem with a Roussel exhibition at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne, co-organised with Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller.) Throughout his bibliographic dredging, Sanchez details Roussel’s propensity to inflate and mythologise his works by various procedures, including the forgery of his books’ edition numbers, the repackaging of older editions, the publication of self-penned reviews (favourable, and under a pseudonym, of course) and the employment of sympathetic audiences at his premieres.

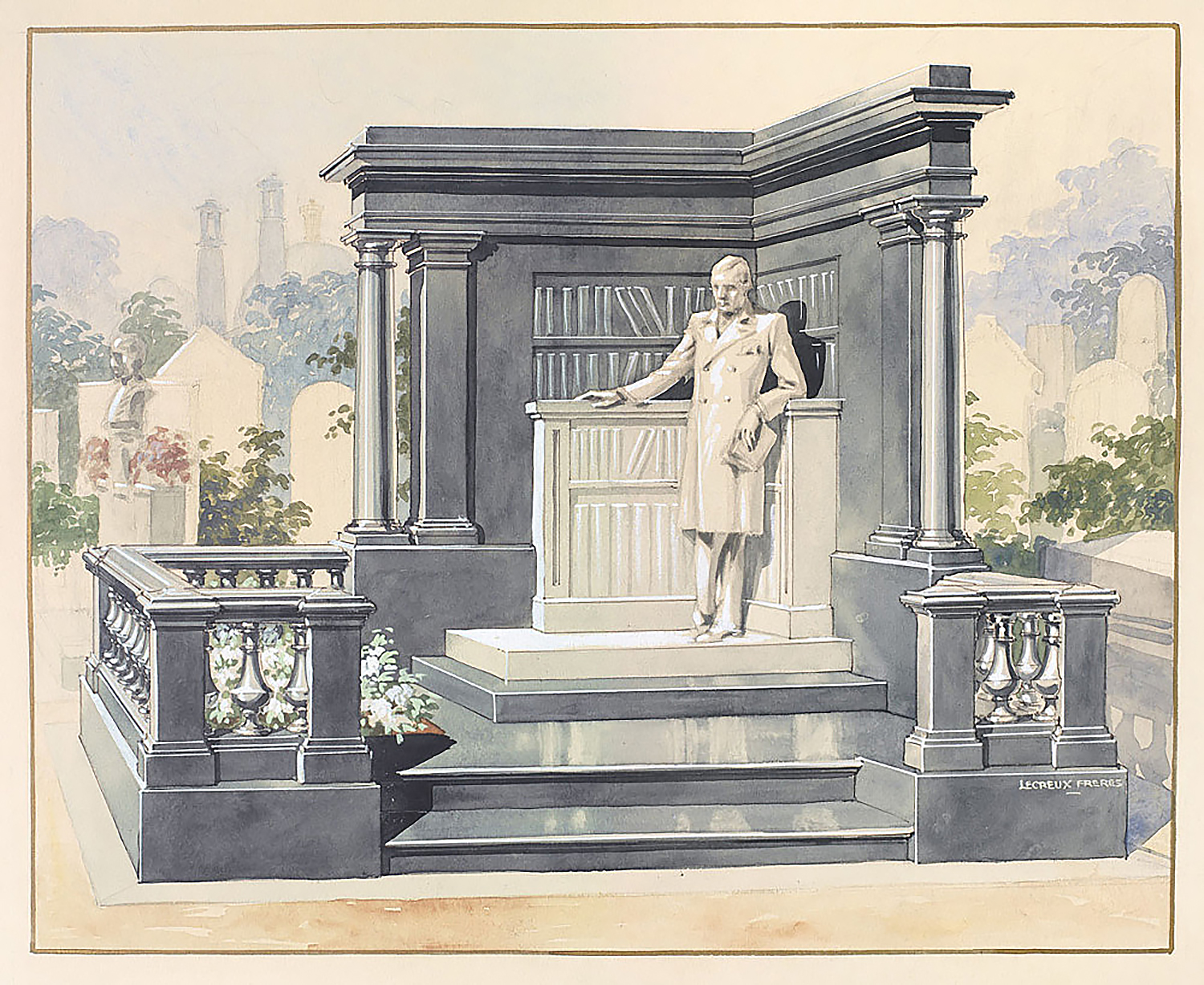

These are but a few of the theatrical machinations that Roussel conducted in his life, according to Sanchez. Others include Roussel’s decades-long employment of a mistress to accompany him to all Parisian social events in an effort to conceal his homosexuality (he had suffered a very public prostitution scandal in 1904); the hiring of children to accompany him to puppet shows; and the expenditure of exorbitant sums of his own wealth on theatrical follies, global travel, inventions and monuments, all of which would eventually leave him penniless.

Sanchez proposes Roussel’s eccentricity was of a piece with his approach to writing, which was similarly baroque and consumed by fantasies of (self-)invention. This was most evident in Roussel’s development of a literary procédé, a sort of elaborate ‘machine’ of homophonic punning, which he would use to produce his bizarre narrative tableaux. His ‘procedure’ would serve as an influential template for later explorers of both inner experience – for example the Surrealists, Jorge Luis Borges, Georges Bataille and Michel Foucault – and speculative language games – Marcel Duchamp, the Collège de ’Pataphysique and OuLiPo, and the poets of the New York School, among others.

But Roussel’s obsession with interiority necessitated the sequester of his narratives from any encroachment of the unmediated real, which he accomplished through the myriad uses of framing/stage narratives, parentheses, hypertexts, panoramas and miniatures in his writings. Such fantasies would also manifest in Roussel’s fixation on his own domestic insularity. Among his inventions, the maison roulante – a ‘house on wheels’ caravan, which Roussel would use to travel the continent with all of the comforts of his living-room – suggests that the author’s vision of locus solus (‘solitary place’) was as much an architectural as a literary endeavour.

These fantasies followed him to his own suicide in 1933 in a Palermo hotel room, which he barricaded with a mattress, simulating a locked-room mystery. Even in death, it would seem that Raymond Roussel could not escape the labyrinth that he had invented in life.

The Books and Life of Raymond Roussel by Michael Sanchez. Galerie Buchholz, €48 (hardcover)