With elections looming, what do accusations of antisemitism in the artist’s work say about a country divided?

‘I felt this would never happen because of who I am.’ This is what Australian-Lebanese artist Khaled Sabsabi said when, in early February, he was announced alongside curator Michael Dagostino as the Australian representative at the 61st Venice Biennale. What Sabsabi meant was: to have an artist of Middle-Eastern descent representing Australia on the world stage seemed too good to be true. And it was. Just five days after the announcement, him and Dagostino had been dumped. Caught in the crossfires of a conservative-led culture war that has been increasingly dividing Australia since the beginning of Israel’s war on Palestine, Sabsabi’s video work You (2007), which depicts the former Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, had been picked up in the Senate Question Time. “With such appalling antisemitism in our country,” argued conservative MP Claire Chandler, “why is the [Anthony] Albanese Government allowing a person who highlights a terrorist leader in his artwork to represent Australia on the international stage at the Venice Biennale?”

Chandler’s question revealed plenty about Australia’s political moment. With a federal election looming, and the dire forecast that a conservative Liberal government will emerge victorious, the snap decision by Creative Australia (the country’s largest funding body for the arts, who both appointed and swiftly dropped Sabsabi and Dagostino) was less about genuinely engaging with Sabsabi’s work and entirely about placating the party most likely to come to power by May this year. The Liberals, it seems, want to align Australia with MAGA 2.0 United States where expansionist plans to colonise Gaza are openly discussed. In Chandler’s mind, Sabsabi – a Lebanese-born artist – was an opportune target. Australia’s Liberal governments have historically undervalued arts funding. The wounds of the 2015 Brandis cuts, which significantly undermined the ‘arm’s-length’ principle that is said to define Australian arts funding, are still fresh for many. That interventionalist approach looks set to continue, with an incumbent Labor government threatening censorship of artists whose work touches politically sensitive topics – particularly those related to Palestine and the Middle East.

Sabsabi’s You, a multichannel tapestry of images and voice recordings of Nasrallah, was more than enough to catch the attention of the right.Yet far from a one-sided celebration of terrorism (indeed, the entirety of Hezbollah was only deemed a terrorist organisation by Australia in 2021), the work implicates and subsumes the Western viewer. All of the footage in You was taken from a widely televised 2006 rally in Beirut at the conclusion of 34 days of war with Israel, which Nasrallah led, from which stills were circulated in global media outlets. When it was installed at Sydney’s MCA, visitors to the exhibition found the image of Nasrallah projected on to them as they entered the space. As such, Sabsabi asks the viewer to recognise their own complicity in their consumption of Western media – a media that likes to present Middle Eastern leaders as terrorists and which frames any opposition to Israel as terrorism.

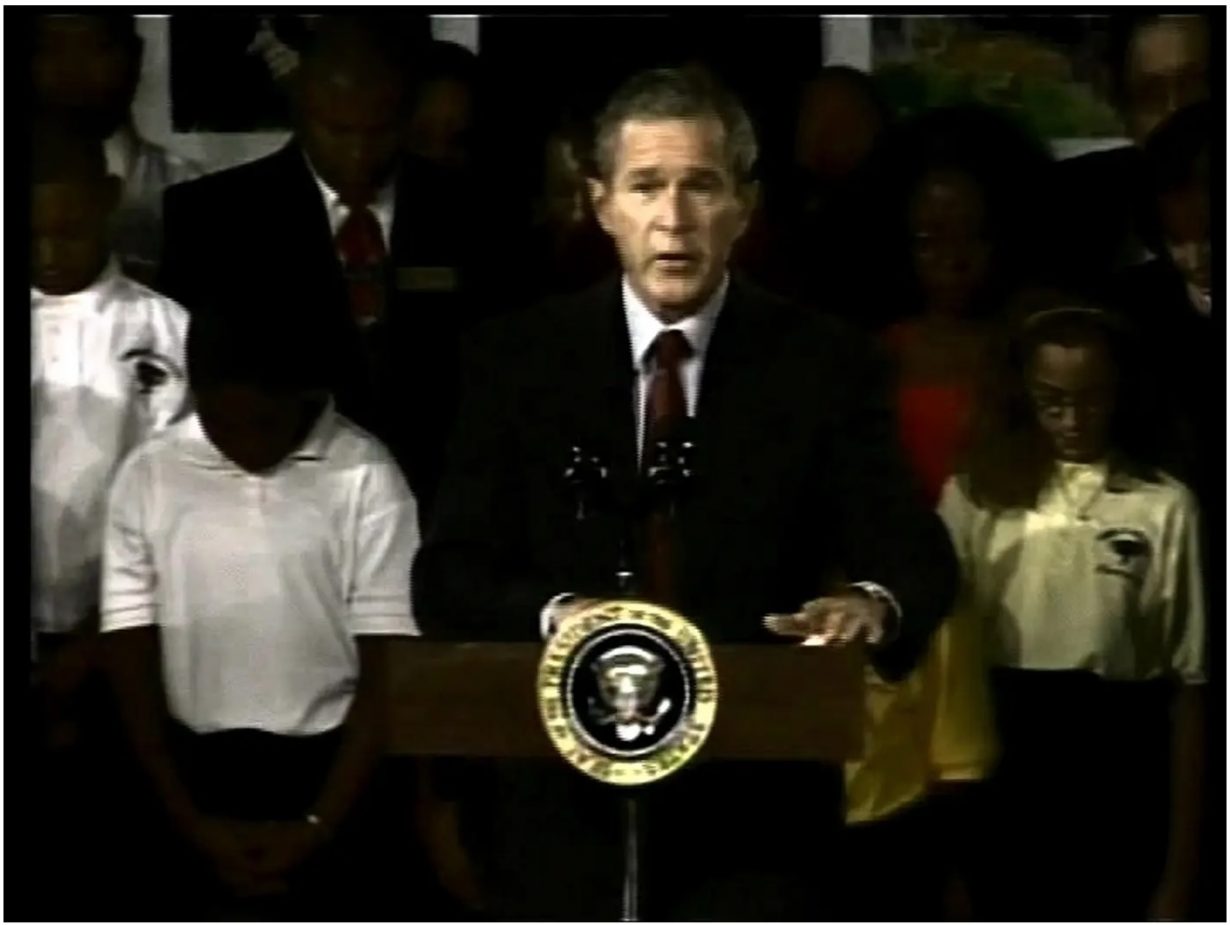

Another of Sabsabi’s works, Thank You Very Much (2006), further stoked the flames for conservative commentators. The 18-second video shows footage of the 9/11 attacks followed by a clip of then-US president George W. Bush saying, ‘thank you very much’. When originally uttered, Bush’s comment was aimed at 9/11 first responders. Sabsabi’s edit, however, suggests that Bush is thanking the terrorists responsible for allowing the president to legitimise the subsequent American invasion of Iraq. Not that either of these readings mattered to Chandler nor the board of Creative Australia. All they saw was one image and one phrase – the image of terrorism and words of thanks – and that was enough. Indeed, whether or not the board genuinely believed Sabsabi’s work sympathised with terrorism (the definition of which continues to morph in Australia), was evidently less important than bowing to the populist outcry of a member of the likely incoming government. It is a decision that amounts to nothing less than censorship.

Summoned on 25 February to account for their actions in the Australian Parliament’s Senate Estimates, Creative Australia’s CEO Adrian Collette and Chair Robert Morgan offered responses that illuminated their knee-jerk decision to remove Sabsabi from the national pavilion. No, a lawyer had not been consulted prior to the board meeting in which the action had been decided on 13 February. Neither Sabsabi nor Dagostino were given the opportunity to defend the work before the board. When asked why the board acted so quickly, Morgan responded, “We considered that this video [Thank You Very Much] would become prominent, divisive and would escalate in an urgent way.” Of course, the irony being that images of both the works in question have been widely reproduced in major media outlets, as a direct result of the board’s decision to supposedly minimise the attention given to them.

Perhaps the most damning indictment for artistic freedom, as well as public intelligence, was Collette’s repeated argument that “the impact of art does not reside with an artist’s intent. It resides in the way it is perceived by the public.” Which public is Collette referring to exactly? It can’t have been the thousands who, in the days after the sacking of Sabsasi and Dagostino, signed their support in open letters that called for their reinstatement (asked to identify their professional position, many simply wrote ‘Citizen’, or even ‘Citizen who appreciates art’). Collette’s patronising comments about the public’s inability to interpret art and nuance seeks to falsely define the public as a homogenous cohort with a single political perspective – right-wing conservative. Not only did Sabsabi’s intention not matter to the board, but their actions also suggest that the ultimate reading of his artwork was theirs alone to make.

Such overt censorship is becoming a troubling occurrence not just in the arts but in Australian institutions more broadly, and it is a symptom of Australia’s rapidly shifting Overton window. Censorship of pro-Palestine speech and support of Palestine’s allies in the Middle East has been prevalent in Australian universities. Students have faced disciplinary action over protests highlighting university funding from and financial investment in Israeli arms companies. In a high-profile unlawful termination case that concluded last month, ABC reporter Antoinette Lattouf was fired when she posted a Human Rights Watch report that alleged Israel was starving Palestinian people. Days after the news about Sabsabi broke, it was reported that a curatorial decision at the National Gallery of Australia had been made to cover up two Palestinian flags depicted on a large tapestry by Pacific Indigenous art collective SaVĀge K’lub. The tapestry was made up on multiple first nations flags – Aboriginal, Torres Straight Islander and West Papua amongst others – and yet only the Palestinian flags were deemed ‘sensitive content’.

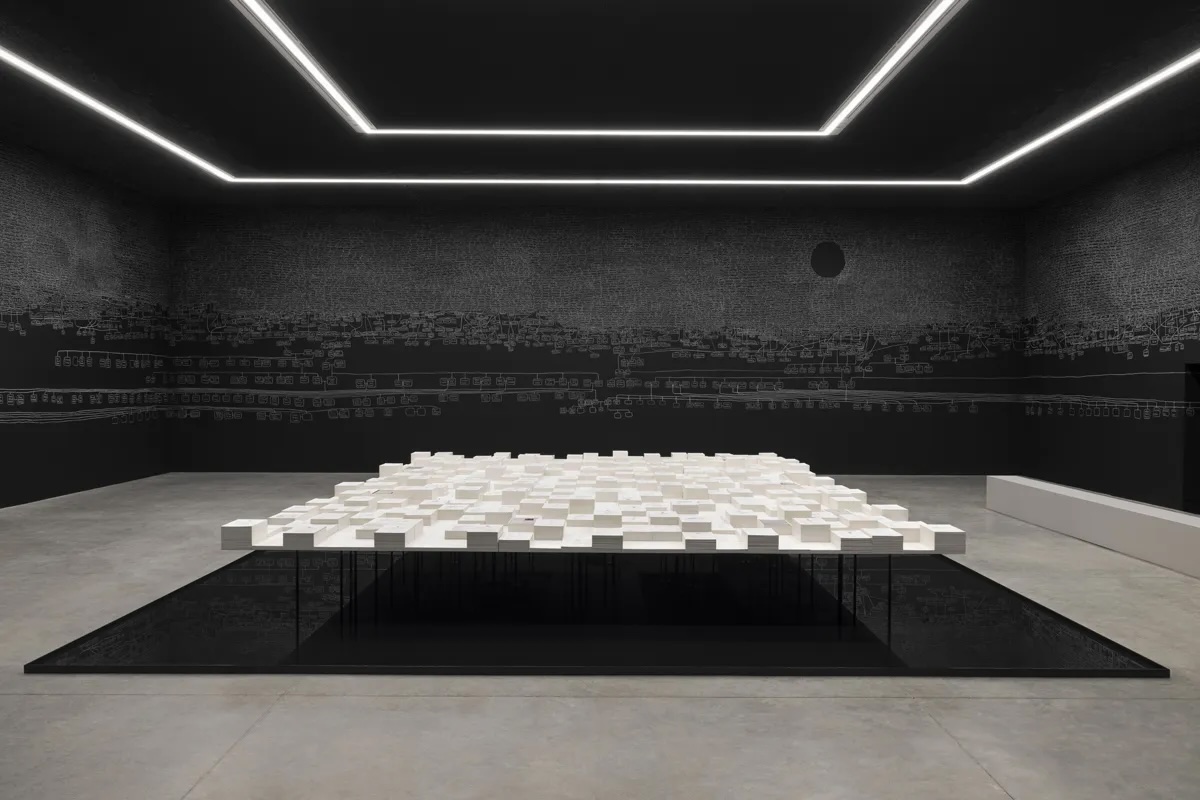

We don’t know what Sabsabi and Dagostino were planning on exhibiting in the Australian pavilion. But backtrack to 2024 and the 60th Venice Biennale, where artist Archie Moore and curator Ellie Buttrose’s presentation, Kith and Kin, evidenced that the public is more art literate than Creative Australia has given them credit for. Moore displayed hundreds of documents, all of which were coronial inquests into Aboriginal deaths in police custody. The physical density of the stacks was a sobering reminder of how many Aboriginal people have died in this manner. Yet despite its difficult and violent subject matter, Kith and Kin was awarded the prestigious Golden Lion for Best National Participation, in a first for Australia. The Pavilion was widely visited, with queues snaking around the building in the weeks after the win.

The problem, then, lies in Australia’s position among widespread Western political conservatism and the attendant diplomatic minefield surrounding Israel’s occupation of Palestine. The Australian government was comfortable with confronting atrocities committed on its own soil in Venice because these atrocities are limited to our own shores. While Aboriginal deaths in custody are a source of great shame for Australians, they rarely make global headlines. In other words, these atrocities would unlikely be questioned by foreign powers with whom Australia maintains diplomatic ties. But, in the eyes of the Creative Australia board, Sabsabi’s work ran the risk of causing immense international outrage.

What are we left with? The 2026 Australian Pavilion is now a poisoned chalice. In the days following the sacking, the other shortlisted artistic teams signed a letter in support of Sabsabi, effectively signalling their unwillingness to take his place. Within twenty-four hours of the announcement, thousands of outraged, art workers and members of the general public had signed open letters calling for the team to be reinstated (on 20 February, the Guardian reported that Creative Australia would not reinstate Sabsabi). For many on either side of the political spectrum, the protection of artistic freedom was paramount, regardless of Sabsabi’s work itself. The pavilion is now expected to remain closed for the biennale.

Collette indicated during his questioning in parliament that both Sabsabi and Dagostino will still be paid (whether they will receive the full amount stipulated in their original contract is unclear), a move that will surely further outrage conservative politicians who already bemoan the use of tax-payer money to fund the pavilion. Sabsabi’s team is now looking at ways to present its project in Venice during next year’s biennale. But even if the project is shown in Venice, the saga is far from over. As Australia’s largest arts funding body, Creative Australia has been severely compromised. If the nation elects a Liberal government this year, we will likely see further cuts to arts funding (as has historically been the case), with Sabsabi and others used as a scapegoat for this move. Has Senator Chandler actually seen You in the flesh? Absolutely not. But if the united front and international uproar in support of Sabsabi and Dagostino is anything to go by, the so-called public is a lot more willing to sit with art and dissect it than they have been given credit for.

Amelia Winata is an editor of Memo Review and former curator of Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne