The school’s members helped forge a vital identity for a newly independent Morocco, but how does this translate in a foreign institution that has failed to learn from the lessons of the past?

On 2 March 1956, following a period of revolt and riot, Morocco declared independence from France and Spain, and was reunified as a single nation. Now free from colonial rule, art schools began to look further than the western styles promoted during the European occupation. In the French Protectorate of Morocco (1912-–56), Moroccan craft guilds were industrialised and controlled by the administration but were physically separated into walled medinas and culturally segregated, seen as inferior to the European paradigms of art – the likes of Eugene Delacroix, Henri Matisse and Paul Klee, who all visited Morocco in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Morocco’s modern visual art scene evolved in tandem with this postcolonial period of flux, grappling with the nation’s new political identity while making sense of the recent legacy of the French-influenced arts education. At the same time, Morocco’s prominent cities continued to be cosmopolitan, international meeting points that attracted artists from all over the world – and who inevitably formed relationships with local artists. At this charged moment in time, the Casablanca Art School emerged as a site for experimentation, political discussion and exuberant exchange – initiating a major shift in the development of Moroccan Modernism away from the European hierarchical view of the country’s art.

A new exhibition at Tate St Ives in the UK, The Casablanca Art School, reimagines a figment of this period of art history too-little-known in the west – this is the first UK museum show about the School, which will travel to Sharjah Art Foundation next year. The story begins in 1962, the year the Moroccan artist Farid Belkahia was appointed the school’s director. Though the school had been established by the French in the 1920s to maintain the French cultural hegemony, much was changing under Belkahia’s leadership: women were allowed to attend the school for the first time; celebrated Moroccan artists Mohammed Chabâa and Mohammed Melehi, returning to the country after stints at institutions in Europe and the US, were enlisted as tutors; the first course on modern art history in Morocco was introduced (taught by art historian Toni Maraini, who met Melehi while he was living in Rome); and a Dutch anthropologist, Bert Flint, who had amassed an immense collection of Moroccan artefacts and art – particularly from the Atlas mountains, including Amazigh rugs, jewellery, ceramics, metalwork and basketry – was brought in as part of a mission to revalorise Moroccan craft.

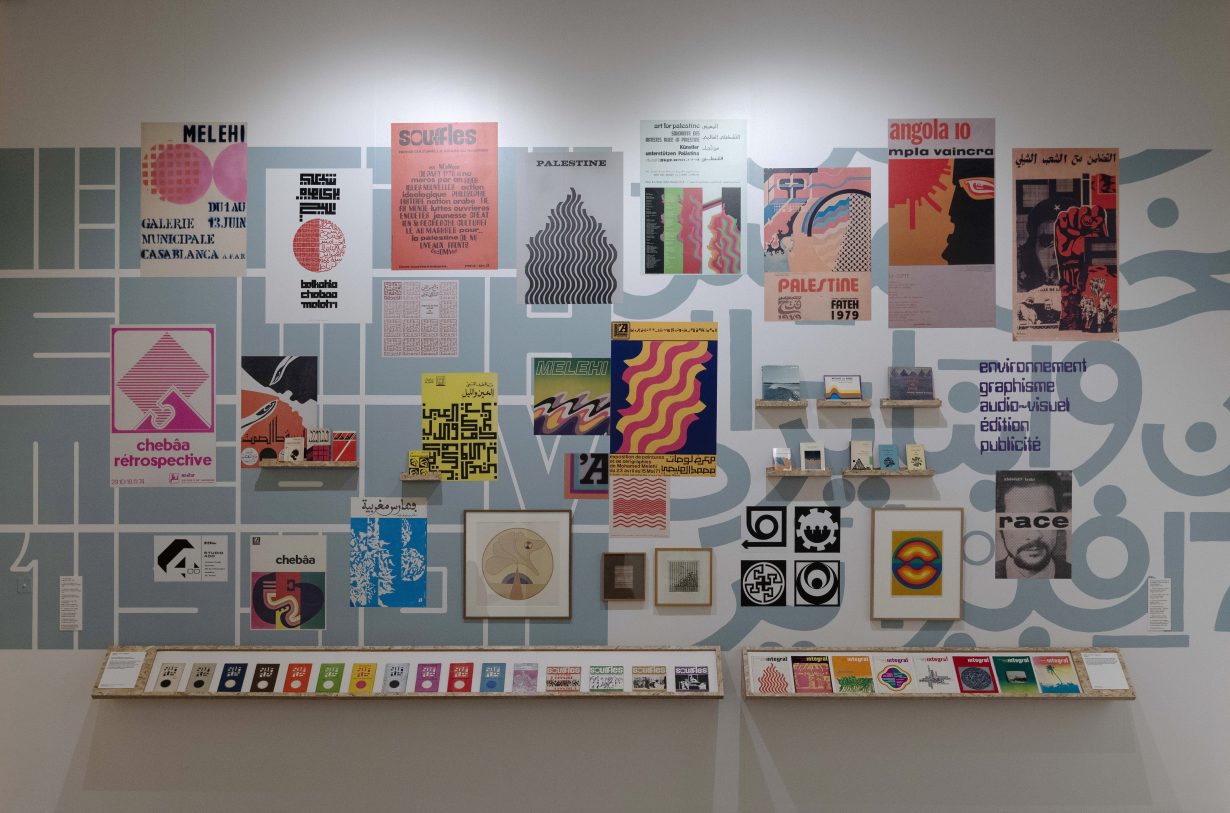

It was a prolific period for the school’s artists and students. They produced installations, publications, posters, sculptures, typography and textiles. Their vibrancy and vitality is evident in the paintings of Mohammed Chabâa and Mohammed Melehi, with their supple lines and hypnotically precise brushwork, sometimes using industrial paint, cellulose and acrylic, and blasts of colour that could contend with the brilliance of the Moroccan sun. Undoubtedly the most accomplished artists and figureheads of the CAS, Chabâa and Melehi, epitomise the movement’s approach, revering Morocco’s past and the cosmic geometries found in Amazigh rugs (made exclusively by women artisans who remain, even in the Tate show where an exquisite Amazigh carpet is displayed, anonymous). But they firmly situated Morocco in their present moment, taking in its own cultural and aesthetic tradition alongside the psychedelic colours and shapes of 1960s Western visual culture. From Casablanca, their work reflected an increasingly cosmopolitan city and drew influence from the world: Melehi, for example, would feature in a 1963 two-artist show with Piet Mondrian in New York before joining the School the following year – ‘I went to the West to learn Western things, but at the same time I came upon Eastern things, such as Zen, and this drove the evolution of my view’, he said in 2019. Throughout the CAS’s works, we are reminded of the clean lines of American Hard-edge abstraction, the technicolour compositions of the Gee’s Bend quilts, or the graphic optimism of Malick Sidibe and Seydou Keita in West Africa, even the hallucinatory effects of British Op Art.

Intertwined in this modest but intensely researched exhibition are several love stories that hint at the personal, private and romantic relationships – as much as intellectual and political ideas – that drove the movement. The major, foundational love story is that of Mohamed Melehi and Toni Mariani, the Tokyo-born Italian writer, poet and art historian. The two met in Rome in the late 1950s after they were introduced by the gallerist Topazia Alliata. Mariani returned to Morocco with Melehi in 1964 and became his second wife; they had two daughters and collaborated on the socio-political journals Souffles and Intergral, where the ideas and images of the school were explored and expanded. Mariani remained in Morocco until 1987.

Another love story that shaped the course of the movement is that of Mustapha Hafid, a student and then professor at the Casablanca School, who studied in Poland, where he met his Polish wife, Anna Draus-Hafid. The pair worked alongside each other at the school – Draus-Hafid set up the weaving workshop there in 1974. There are affinities between their neo-expressionist works, in a preference for utilitarian materials, organic shapes and earthy hues. In a huge textile piece by Hafid – extremely rare, since most of Draus-Hafid’s works have not survived – entire chunks of wood are sewn, with some vigorous needlework, onto textile a mesmerising merging of collage, sculpture and painting, combining Eastern European and Moroccan aesthetics and techniques. It is arguably far more impactful than any of her husband’s paintings. Yet Draus-Hafid, like many of the women of the school and of her era, has remained in obscurity until now. Another little-known romantic connection also existed between the Italian artist, Carla Accardi, who spent extended periods of time in Morocco in the 1970s and collaborated with Belkahia, Chabâa and Melehi, and Mohamed Hamidi, an artist and professor at the CAS. She was, for a time, Hamidi’s lover, too. These relationships evoke a more intimate and human perspective on the varied work that emerged from the scene during these years.

To try to emphasise the porous, sprawling nature of the Casablanca School, however, the Tate exhibition relies heavily on archival documentary footage, hazy films and photographs, vitrines and reproductions that reconstruct its pioneering activities but belong firmly to a distant time and place. They begin to feel exoticised. As a reaction to the segregation under French rule and as a solution to the lack of museums and exhibition spaces, the Casablanca School artists brought their art to the streets with murals and exhibitions such as the 1969, Présence Plastique in Marrakech’s Jemaa el-Fna Square and in the 18 November Square in Casablanca. A flyer was handed out to passers-by: ‘we hung our works here for ten days… to show works outside of the closed doors of galleries and salons, where this audience has never been…’

Seeing these dynamic attempts at breaking the conventions of colonial display in the anodyne rooms of a western museum feels at odds with the school. The artworld now is hellbent on history, on redressing the past and highlighting the chapters that have been ignored by imperialism. But in doing so it fails to take on any of the lessons of the past. The exhibition underlines the fact that, in the intervening decades, the west hasn’t come very far in how we think about narrativising and presenting art, and who it is for. A school that urged decolonisation is recolonised – validated by its presence behind the same closed doors it boldly broke down half a century ago.

Charlotte Jansen is an art and culture journalist based in London. She is the author of Photography Now (2021) and Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze (2017)