“Moving differently is thinking differently”

Peering down from a walkway connecting the two upper wings of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof, I see small figures moving around a lifesize sand dune in the ground floor’s historic hall. From here the figures, though human, look like ants. To their left and right, spindly silver spider-leg-like structures spill out of crates and rest, some still wrapped, against towering metal support-beams. The crates, along with the sand, had arrived at the museum four days prior, along with the Romanian artist Alexandra Pirici. The dune and silver structures will soon be joined by chemical gardens growing in glass cylinders; liquids automatically changing colours due to their physical properties; human performers and more to create Attune, Pirici’s new site-specific installation.

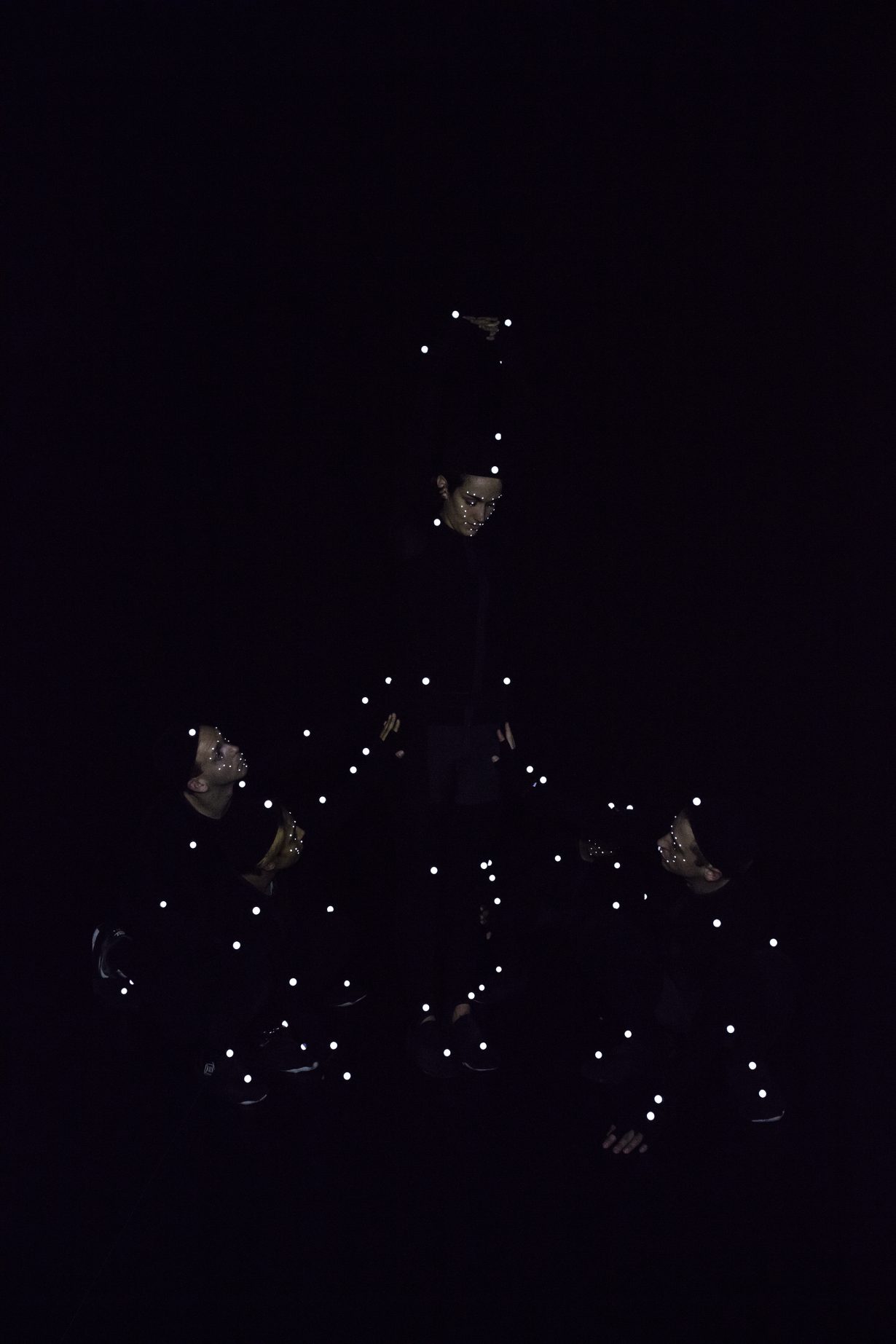

Attune is a natural expansion of her overarching practice. For more than a decade, Pirici has choreographed ongoing actions and environments that bring together elements of dance, sculpture, spoken word and music to reflect on everything from art history and pop culture to questions about where the body begins and ends to our relationships with other forms of being. When Pirici represented Romania at the Venice Biennale in 2013, performers embodied artworks from previous iterations of the Biennale. For Signals (9th Berlin Biennale, 2016; Kunsthaus Zürich, 2017), performers wore motion-capture suits, acting out a stream of images and information akin to a content-ranking algorithm creating a newsfeed; their movements were prioritised based on input provided by audience members, or ‘users’, who could select news items on a related website in real time. In Aggregate (Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, 2017; Art Basel, 2018), over 60 performers formed a living time-capsule of human expression; references expressed in movement and sound ranged from Depeche Mode’s 1990 song Enjoy the Silence to Michelangelo’s David (1501–04), Wifredo Lam’s 1950 painting Lisa Mona, Bollywood movies and Romanian folk music. Then, as part of Cecilia Alemani’s Venice Biennale in 2022, Pirici debuted Encyclopedia of Relations, which centres on embodiments of collective relations as seen in biology and botany.

For Attune, a co-commission by Hamburger Bahnhof and Audemars Piguet Contemporary, she is building on all of this while expanding the focus to also include the nonliving. Here, various types of matter from both the natural and humanmade worlds will show that being inanimate does not equate to being inert. Taking a break from the installation process, we walk over to the museum’s café, order coffees and dive right into the subject at hand.

Self-organising Matter

What was the starting point for this show?

“The main idea is that matter has the capacity to self-structure and self-organise,” says Pirici. “The most recent developments in chemistry and physics make it clear there is no ontological or fundamental difference between systems that are alive, like biological systems, and systems that are not alive but that can behave in ways similar to living matter. This [show] marks a development into the realm of the more-than-human but also the nonliving which nevertheless is active.”

Although engaging with species beyond humans is not new to her practice, working with the entirely nonliving – a sand dune, experiments with liquids – feels like a relatively big jump to make. So, I wonder, how did you come to this development?

“I was reading Order Out of Chaos [1984] by Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers, which is about dissipative systems, and I became interested in how systems that are unstable and in nonequilibrium come to a point where they have to restructure themselves and actually have the capacity to do so. In biology one example is morphogenesis, a process through which there is cell differentiation, and a cell, tissue or organism starts to acquire a form. There is a local interaction between smaller elements of a system – and when I say system, it could also be an organism – that creates a logic or structure. In nature a clear example is murmuration: the way in which a large flock of starlings manages to move together without someone directing them. Sand dunes are also the results of a self-organising process; they self-structure. They’re also beautiful, sculptural, active elements.”

Science Mustn’t Be Reductionist

In addition to chemical gardens and automated experiments producing colour-changing substances, the show will stage a largescale version of the Bénard convection cell experiment, from 1900, which shows how cells form specific patterns when a liquid is boiled. Typically invisible to the naked eye, the phenomenon becomes visible when something like mica powder, which reflects light, is added to a liquid. Why did you choose to work with scientific experiments alongside matter from the natural world?

“I’ve always been fascinated by the scientific perspective, and I was interested in including examples from science or the world of the lab in something that feels more like a story. Today, I think science is seen either as something that is going to save the world or as a field that has sold out to the military-industrial complex. I perceived this growing distrust in science, and it is too reductionist – yet it doesn’t have to be. We think about Newtonian physics and this mechanical world that is rationalist and reductionist and it allows for one door [to open]; but that is outdated and belongs to a different era of science. I’m interested in the continuum between the animate and inanimate, between us and a chemical reaction.”

In other words, bringing scientific experiments into the exhibition reframes them. Instead of being reduced to one of two poles on a very large spectrum, science becomes, once again, part of our larger, more complex, human story – one with, as Pirici says, “movement and song and action”.

Chemical, Bodily and Aural Transformations

Bringing together organic and inorganic matter to form self-structuring sculptures, choreography and song is the crux of this new work. What is the process like, thinking about these examples of self-organisation and then translating them into the work?

“I read a lot and I also move, and somehow these two processes come together.” At the start of a project, she adds, “I work a lot on my own. I’m not enough, because there will be more performers, but I try to imagine and anticipate how people will move.” For the performative aspects of Attune, “I am thinking about how I relate to [the self-organising processes]. There are parts where the human performers embody certain self-organising processes, but there are also parts where they sing.” When it comes to the experiments, Pirici worked with her partner, who is also the show’s set designer, Andrei Dinu. Together they tested some of the experiments “at home in very safe conditions”, before joining forces with professional chemists to develop ways of scaling up to transform small lab experiments into giant sculptural works.

What is the significance of the physical human embodiment?

“There’s something interesting in the capacity of trained performers and bodies to become other. If you don’t think of yourself only in a bipedal position and you bring your body into other forms, other dynamics and ways of moving, it does something to your brain. I think it enlarges your perspective and makes you approach otherness differently. I think it makes your brain more fluid as well. Moving differently is thinking differently.”

And embodiment through sound?

“When it comes to sound, I’ve always been interested in music and I’ve always sung, but I was also inspired by the space [of Hamburger Bahnhof] to sing more. First of all, sound travels the best in space. It’s the element that can take up space most efficiently. Secondly, I think our intellectual experience of something has to be connected to pleasure, so singing about a chemical reaction might be a more pleasurable way to become curious about that phenomenon.”

“Then there’s a certain availability to shift, which I find interesting from a political point of view,” she continues. “I’m interested in working with polyphony and polyphonic structures –multiple voices singing slightly different melodic lines at the same time. It’s such an uncommon form of composition today and it also produces a very uncommon sound. Modern music is so much about one thing; polyphony is very challenging for the modern ear. And there’s a political meaning to being able to hear more voices, to harmonise them. You have to listen to yourself and the other at the same time. This is an interesting training to perform and also to hear – to truly listen to this polyphony of voices, to this multiplicity of voices that are different but can nevertheless coexist. Maybe this is the training we actually need.”

Technology Is More Than a Tool

The algorithm employed in Pirici’s Signals was just one part of the whole, which she says “was about the [human] relationship to the Internet”. In another piece, Leaking Territories (2017), conceived for Skulptur Projekte Münster, performers collectively embodied a search engine, acting according to the parameters of a Google search: an audience member could call out a search term and the performers would analyse the querier’s appearance and subsequent reaction to continually recalibrate their personalised answers (delivered by way of sound and movement). With such pieces in mind, I ask, are you still using or thinking about technology?

“Yes, it’s always in my head,” Pirici replies without hesitation. “I come from this world of movement, but I still like to talk about the digital space, virtual bodies and technologies. I’ve been reading and thinking about algorithmic structures and machine learning. Here, I’m planning to include a reflection on machine learning systems, because they are also talked about as self-organising; they rely on human design, but then they do things on their own.”

How do you see technological self-organisation in relation to self-organising processes found in nature?

“When you speak about self-organisation, you also have cybernetics and cellular automata, which is all about modelling pattern formations. For example, there are seashell and animal patterns that are examples of Turing patterns and can be modelled with cellular automata, and I’m including a reference to that. Because, again, what is interesting to me is that this very material world of graspable, active, intelligent substance need not be and is not opposed to mathematical modelling and computation. We are not machines, but some parts of us are.”

Matter Possesses Its Own Spirit

Without any specific prompts, Pirici speaks passionately about her research into self-organising structures and process, as well as her more conceptual interests, going off on captivating tangents throughout our conversation. After explaining some of the various chemical experiments she is working with in Attune, she muses: “It’s fascinating to observe something we normally believe to be inert. We believe there is a clear difference between something alive and something inert, but it’s just about existing in certain conditions in which inert material starts doing something. And this has really important implications for our place in the world.”

Such as?

“The whole discussion of the origin of life: abiogenesis came from inorganic matter that, under certain conditions, started to produce something and metabolise. It’s a kind of materialist perspective on the world, where matter doesn’t need a transcendent spirit to activate it; it already contains its own spirit, and it has the capacity to produce life. And this ties into larger theoretical fields and philosophy, maybe even the actor–network theory, as well as [what are commonly understood as] metaphors about the world where we are the same as stardust or rivers. And in the end, these are not metaphors: it is scientific reality.”

Towards the end of our conversation, we zoom out and return to the title. Beyond the obvious connection of attuning one’s ear to the polyphonic voices, why did you choose the title Attune?

“I think about it as an invitation to accept or to understand and harmonise with this reality of intelligent, vibrant matter,” Pirici says. “It’s important today to also reclaim science from reductionist tendencies and, this sounds really pretentious, but to rediscover or to make a new attempt to understand our relationship to other forms of matter. In the end, it’s just other structures; the difference is in the configuration. There is no essence, which is maybe also disturbing, because maybe there is no soul, there is no architect, there is no God. Everything is within – and this is also how we, humans, came about. That’s wondrous.”

Attune is on view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, through 6 October

Emily McDermott is a writer and editor living in Berlin