“The old-fashioned language feels so disconnected from today’s world, and out of that dissonance arises a kind of humour. What I value is humour born out of contradiction, not critique.”

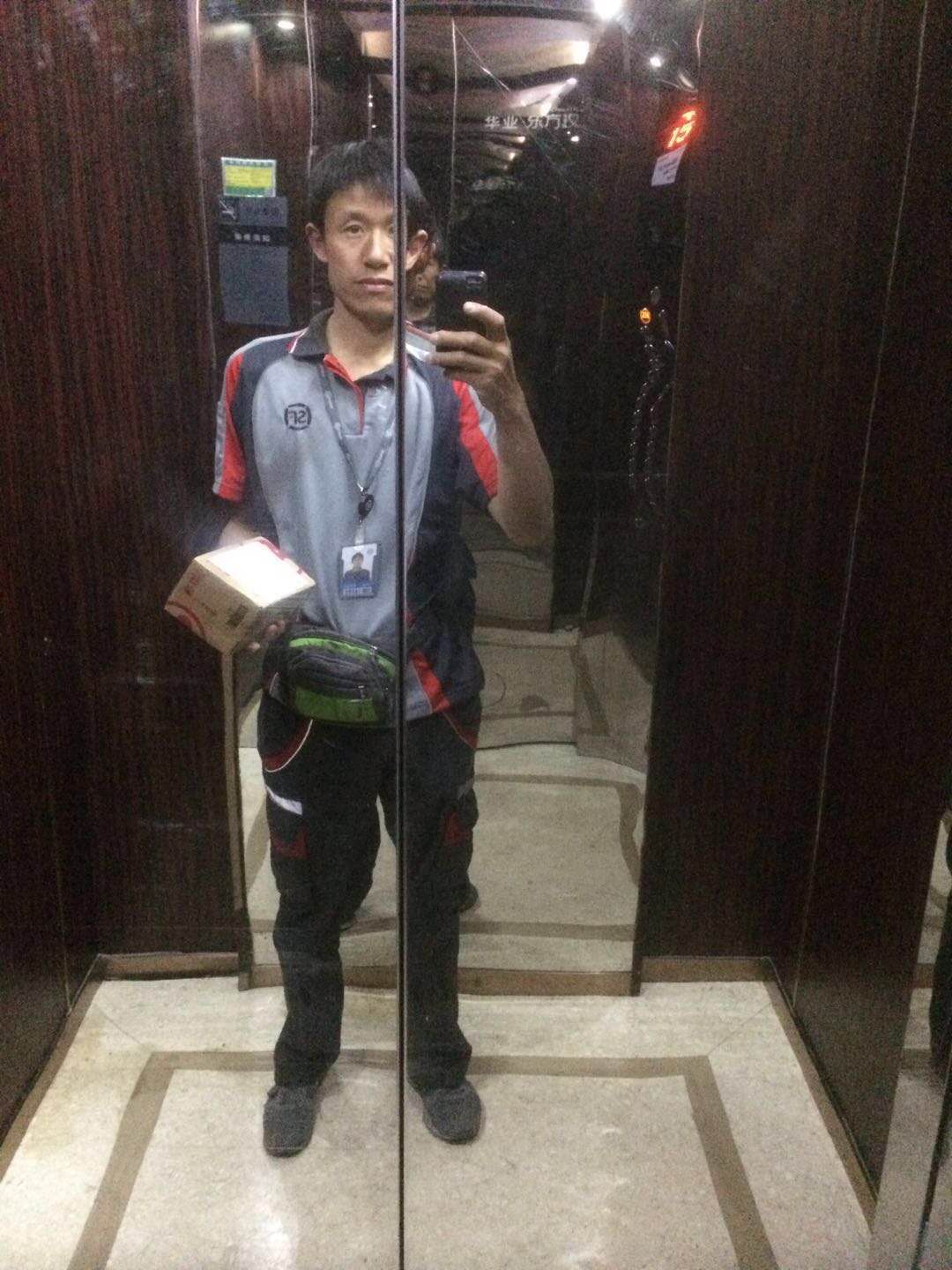

Almost every introduction to the writer Hu Anyan begins with the number of jobs he has held since graduating: 19. The three nonfiction books Hu has published in Chinese have detailed almost every single one of these vocational experiences, and the journey that saw him move from job to job across China. Among many other things, he was a comics apprentice in his hometown, Guangzhou, a clothing-shop owner in Nanning, a security guard in Dali, a bicycle salesman in Shanghai and finally a delivery driver in Beijing – the job that launched his literary career. A web journal Hu wrote delineating his nights at a large logistics company in China went viral in 2020, marking something of a watershed moment for him, though he had been writing for more than a decade by then. In 2021 Hu secured a book deal and moved to Chengdu, a second-tier city in southwest China – not for another odd job this time, but to write.

ArtReview Asia sat down with Hu in Chengdu shortly before the publication of his bestselling first book, I Deliver Parcels in Beijing (2023), in English for the first time. We met and chatted in the lobby of a movie theatre inside a shopping mall. He had been coming to this weird nonplace to write almost every afternoon. In person, Hu speaks with the same humility and frankness that run through his prose. It is apparent that a writer like Hu asks little of the outside world. Freedom can be hard to see in a quiet corner of an air-conditioned mall, but not for Hu, who knows better than most of us about what it means to work, and all the drudgery and solitude therein.

A Day in the Life

ArtReview Asia What are your days like? Do you set a goal for yourself to write a certain amount each day?

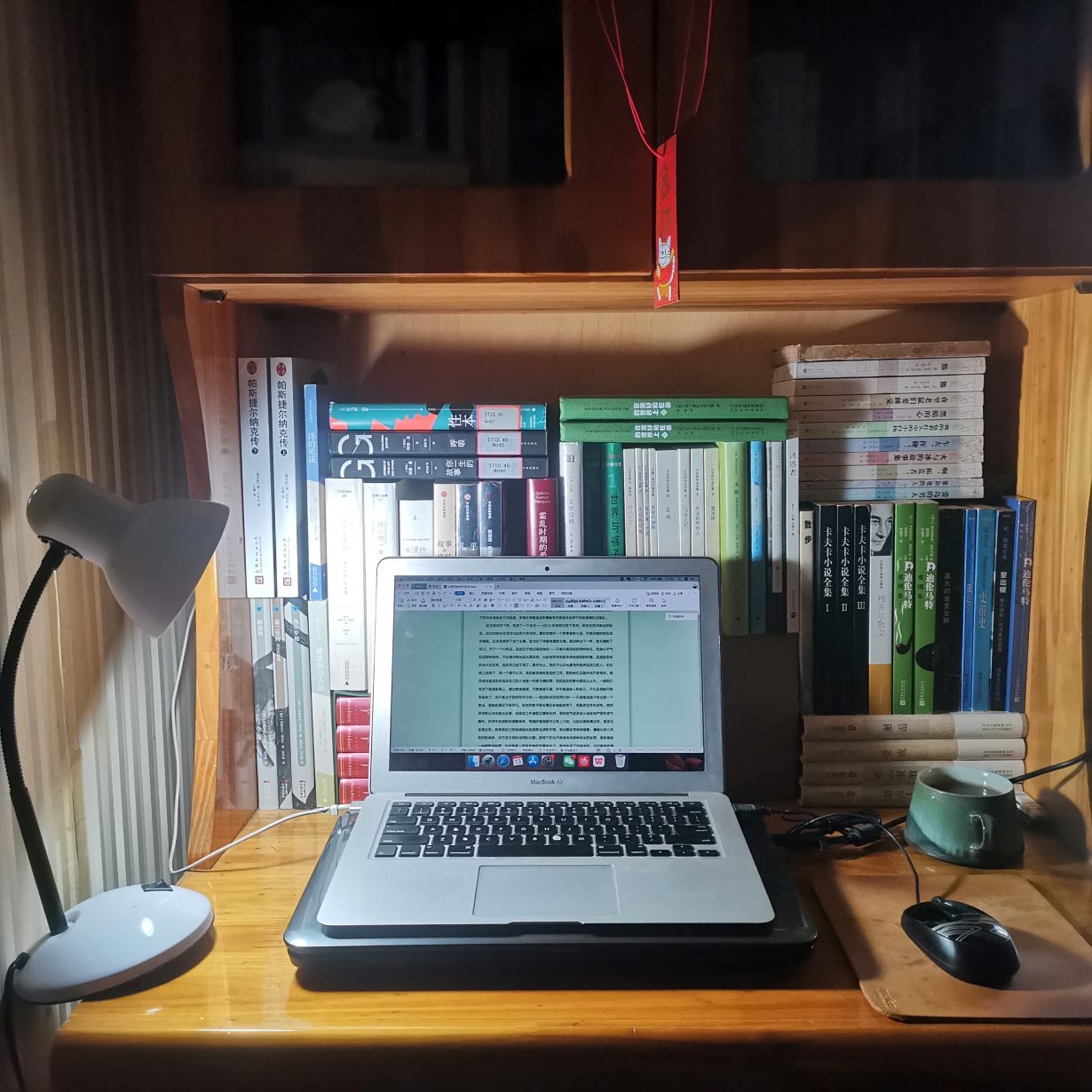

Hu Anyan Sort of, but I’m not strict about it. Usually my wife and I write in the afternoon. I’m in charge of cooking, and lunch is our main meal of the day. In the morning I go grocery shopping and cook. After finishing the chores I go to the library to write.

Our rented apartment has only one air conditioner, in the bedroom. In the summer the other room gets so stuffy and airless my wife and I have to go out to work, ‘freeloading’ on air conditioning in public spaces. This past August we frequented the local library almost daily. But during school vacations in the summer and winter the library gets too noisy with kids and their parents. We’ve recently found this relatively empty shopping mall – a really good substitute for the library. The mall is quiet, has free wifi and air conditioning. There is also a buffet-style vegetarian restaurant on the fifth floor. After 1:30 pm it only costs nine yuan [£1] per person.

ARA That’s very cheap, even for a city like Chengdu.

HA The food is good, with a large variety of dishes. Some people go there because of their Buddhist faith, others just like the food. After a few visits, my partner and I stopped cooking for ourselves. The only downside is that we have to wait until 1:30 pm to eat.

ARA Does living by a routine and repeating the same cycle each day make you anxious at all?

HA Not really. But in terms of creative anxiety, these days I feel a lack of strong motivation, particularly because I’ve been writing passively, as opposed to following a pure drive of my own.

ARA Meaning you’re only working on commissions from editors?

HA Yes. Recently my writing is largely motivated by external prompts. My own projects, especially fiction works, progress slowly. I’ve long planned to complete a novel, but it’s been difficult to maintain a good working rhythm.

When I moved to Chengdu in 2021, my first book hadn’t been published yet, though the manuscript was finished. In fact, I didn’t know if and when it would ever be published. More than a year passed in uncertainty. Those days I was writing for the Chinese literature forum Heilan, together with its founder Chen Wei and other writers. Some of the essays I wrote for Heilan were collected into my subsequent books. But when I wrote them, they weren’t meant for publication – they were just pieces I wrote alongside other writers out of camaraderie for no pay. After I Deliver Parcels in Beijing came out, things got busy and my writing rhythm was a bit broken.

Nonfiction vs Fiction

ARA When your nonfiction essays began attracting attention online, did you sense that these works resonated more than your fiction works?

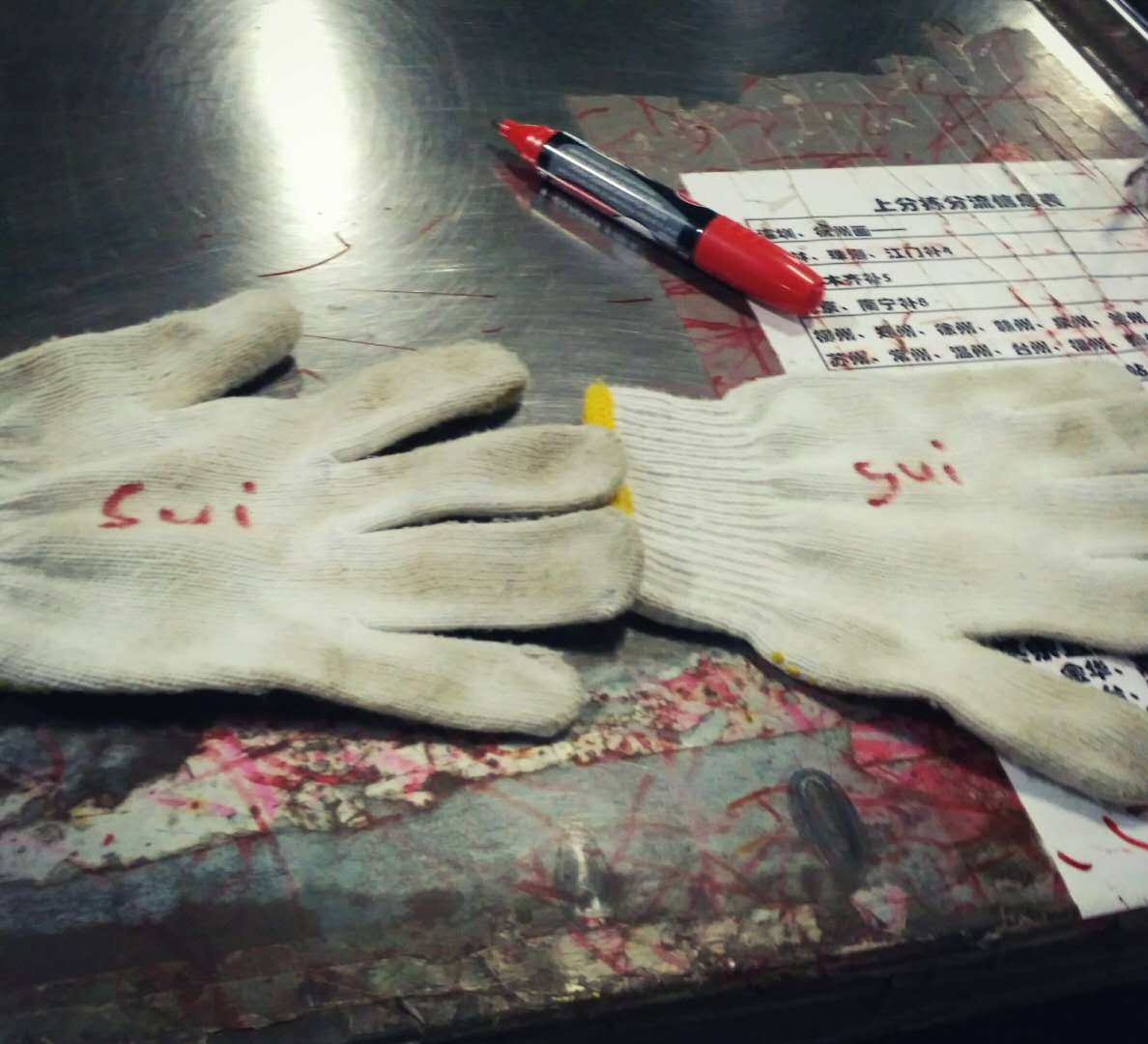

HA Judging from the outcome, yes. It’s apparent that the readership for nonfiction is much broader. Nonfiction simply travels farther than fiction. People started approaching me after the piece I wrote about a year of working nightshifts at a logistics company became popular on the website Douban.

ARA What about your own feelings towards writing in these different genres? Did writing nonfiction feel more natural to you?

HA It is much easier for me to write nonfiction. You don’t need to devise a storyline, you just have to think back and recall as many details as possible. Not much technique is required. In fact, when writing a memoir or autobiography, you must be cautious with literary techniques, as they can be counterproductive and detrimental to what you’re trying to do. It’s better to describe things plainly, in your own voice. Write about what truly concerns you, and try not to think about how others might perceive you and what they might think is important.

Some people say my work doesn’t adequately reflect the condition of a particular profession or social class. But that has never been my goal. If portraying a particular social group was my intention from the beginning, I’d write more journalistically, which isn’t my strength. When I write, I write about the people and events that left the deepest impression on me, even if they don’t represent a broader reality or particular community.

The same goes for fiction: as a writer you’re drawn to the most indelible and indigestible material – the things you just can’t let go. With fiction, you can transform these materials, rearrange the timeline, transfer someone else’s experience onto your own, and the other way around – all to maximise an emotional impact and symbolic significance. Plotting and fabrication are part of fiction as a creative artform, but completely incongruous with the ethics of nonfictional writing. With nonfiction, you just need honest thinking – the way you think is already a part of you and your habits. What you choose to write and not to write is a direct reflection of your personhood. All of these instincts come very naturally to me. That is why I find it easier and faster to write nonfiction, sometimes a few thousand words in a day, while fiction might take much longer, even just a few hundred words a day.

ARA Reading the first three books you’ve published, I could sense this distinct voice that you possess. Your writing flows naturally – or it’s made to feel natural – while you’re able to describe your experiences and feelings with sharp clarity. There is an earnest and honest tone to your voice. The rhythm of your prose has its own form, yet that form never conflicts with the unaffected words you choose. I’m curious, did you put a lot of thoughts into the style and tone of your writing?

HA I didn’t think much about style or tone at the time – it was just what felt natural to me.

ARA So you didn’t spend much time revising sentences or try writing them in different ways?

HA Not really. I rarely overthink style or form for nonfiction. But when writing fiction, it’s different. You might pause when the tone feels wrong. Sometimes you even borrow another writer’s rhythm to get started. Writing about personal experience doesn’t require the same level of deliberation. But it’s not entirely natural either, perhaps it comes out of a skill honed from years of writing fiction. It all feels fluid and instinctive to me now. That kind of naturalness, I think, is something trained, not innate.

To be honest, I get a bit embarrassed when I reread my earlier books. I’ve actually already revised the first one; the last chapter about my early years feels prejudiced and immature now. The second book grew out of a series I published on Heilan with tight deadlines, so there are blemishes.

ARA Do you often reread your past works?

HA Only when necessary. Frankly, it’s a bit painful. There are parts in the first three books that make me cringe. In the first book, the sections about working in Shunde, Beijing and Shanghai hold up better than the rest in my opinion.

ARA Is it the writing or the experience you wrote about that makes you uncomfortable?

HA In the writing I could feel that I was not totally sincere and just trying to get the job done. For I Deliver Parcels in Beijing, the first three chapters were already finished when I signed the book contract, but I added a fourth because the publisher felt the book was too short. That addition wasn’t entirely heartfelt for me. I didn’t feel a strong connection to the materials I was excavating.

ARA Is it possible that the insincerity you’re self-conscious about might not be evident to others? It’s more embedded in your own experience and feelings with the text.

HA I’m not sure, but the process of writing is important to me. As I write, I develop a deeper understanding of myself. The act of writing carries great significance. I remember writing during the pandemic lockdowns in 2022, incessantly reflecting on my past while facing a rather odd reality.

‘Amateur Writer’

ARA What do you think of the label ‘amateur writer’? Is it meaningful or helpful for you in any way?

HA I denied this label from the very beginning. In an interview with The Paper in 2023 I expressed clearly that I was not a so-called amateur writer. And they made it the article’s headline. But efforts to reject the label have proved useless, it doesn’t change how others see you. Correcting other people relentlessly would just seem pretentious. So now I just let people think what they want.

ARA But you still resist being painted as this ‘delivery worker with a literary passion’.

HA That’s never how I see myself. I try to clarify when I can, but it doesn’t always work and I can’t respond to everything. The term ‘amateur writer’ is very ambiguous. Many people who are labelled this way don’t fit into the category. Many great writers could be called amateurs. Kafka, for example, worked in an insurance office. Writing wasn’t his job. If Kafka counts as an amateur, then the term itself becomes meaningless.

ARA The word ‘amateur’ also implies that they are not supposed to be writers.

HA Everyone interprets it differently – some from the angle of hobbyists, some focus on the anti-establishment aspect, some in contrast to full-time writers. These days people need immediately digestible concepts rather than deep distinctions between authors. So labels become convenient tools. For promotional and marketing purposes, it’s almost unavoidable. And I have also benefitted from it.

Humour and Critique

ARA The English version of I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is finally out this year. An introduction on the publishing house’s website described you as someone with ‘deadpan humor and a strong idea of self ’. I wonder if you agree with that description, especially about your sense of humour?

HA I do. I value humour a lot, though it’s hard to express directly.

ARA I can sense a deliberate reversal or breaking of expectations in the text at times. It reads like a calm comedy, composed, but funny in a quiet way.

HA I hope that’s how it comes across! Humour is very important to me, but it’s frequently misinterpreted. For instance, when I wrote about IKEA banning customers from sleeping in the store, some readers saw it as a social commentary. But to me, it was simply amusing.

ARA Do you think perhaps your humour stems from the sincerity in your language, which then creates irony?

HA It’s not irony per se. I actually understand IKEA’s reasoning, it makes sense from their perspective. But there was something funny about the situation. I used phrases like ‘proletarian solidarity’ to describe what I had to do for a fellow courier at the express logistics company, but when that gets translated, foreign readers might mistake it as a serious comment, when really it’s just a way of speaking I inherited from my parents. That old-fashioned language feels so disconnected from today’s world, and out of that dissonance arises a kind of humour. What I value is humour born out of contradiction, not critique.

ARA To me your writing is funny precisely because it’s realistic. Reality itself is quite laughable sometimes, and you tend to describe things in a calm way, where we cannot be certain whether you’re humorous in a conscious way.

HA Maybe that’s true. Seeing my own experiences through humour helps me stay light. Humour is a buffer, it prevents people from breaking under pressure. When tension builds with no outlet, it can snap all at once, leading to harm. But being able to make jokes is a signal that we are still safe. What I really care about is the sense of playfulness in my writing, not treating it as something serious or critical.

ARA I would say your work does contain elements that are critical, though not in the sense of a conscious attack or exposé. A critical awareness naturally emerges from your observations. For instance, when you wrote about your experience working at the large logistics company in Beijing, you touched upon the inequalities and ill treatment of workers with these courier platforms, though you avoided a harsh critical tone.

HA I tried to be as objective as possible. But my experience with the logistics company, for which I used a pseudonym, was generally negative, and I omitted some even worse aspects.

It Runs in the Family

ARA There is a very revelatory, and in a way vulnerable, chapter you added to the third book about your family history. The extent to which you’re revealing and analysing your familial background is remarkable.

HA After the publication of my first two books, readers raised questions and doubts regarding the life decisions detailed within them. While I can’t be entirely certain this was my sole motivation, writing about my family became a form of response to these wonderings. I felt the need to explain where I came from – my family, my parents’ families and the decisive influence they had on me.

The way my parents raised me, the way they expressed affection and even the way they lived their own lives have profoundly shaped who I am. I inherited a lot from them, in temperament, in conduct, in values, and I don’t think I’ve surpassed them in any way. But my parents themselves had almost no perception or awareness of the qualities they possess.

ARA That has a lot to do with their time. Their generation went through such intense social upheavals without knowing how those experiences might have affected their behaviours and psyches. As they navigated an increasingly competitive and interest-driven society in the new era, they might not have recognised the alienation and fear these shifts engendered. I observe a distinct resemblance between your personality traits and those of your parents, especially in your descriptions of workplace interactions in the books. You see stoicism and virtuousness in the family – embracing isolation and rejecting personal gain through competition, all while upholding their principles.

HA I might not use the same descriptions myself, but I understand what you mean. It’s accurate in a way. My father lived his life pursuing integrity – never seeking personal advantage, never acting for private satisfaction. Everything he did was guided by a sense of justice. In that era of material scarcity, moral idealism was almost the only way to maintain social order. If society had encouraged personal gratification when resources were insufficient, it would have led to growing resentment, chaos and perhaps even the collapse of the system. So people turned to moralism as a kind of survival mechanism. But moral preaching alone wasn’t enough. Strict punishment was needed to enforce obedience. People had to believe that any violation of rules could lead to severe consequences. Only then would they comply, at least outwardly, maintaining a fragile sense of order. At the same time, the system also relied on division – redirecting public anger by making different social groups fight each other. When the masses vented their frustration through internal conflicts, they no longer united against those in power. One political campaign after another served to disperse what might have been a collective force. Though of course, writing about this is too risky…

Hu Anyan’s book I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is published in English by Allen Lane in the UK and Astra Publishing House in North America

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.