“I made a point of saying I don’t want to talk about my identity, and the artworld seemed to listen. I think we have a choice.”

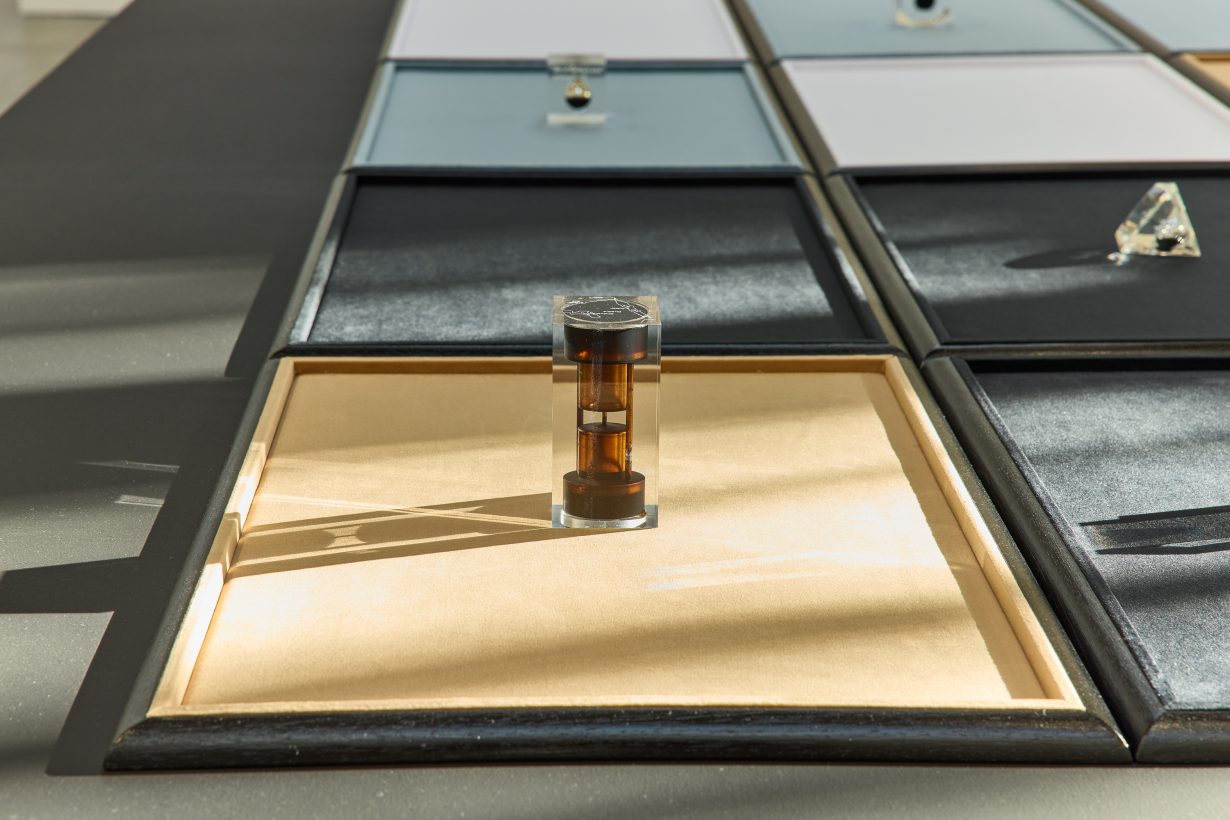

A large grid structure stands solid in the centre of the room, each square outlined in black, inners filled with Italian velvet. Shiny glasslike objects of various shapes are arranged, seemingly randomly, like chess pieces on a board, each encasing an opaque black liquid: crude oil.

These 32 kitschy trinkets are part of Tanoa Sasraku’s collection of paperweights, each representing a different geography cradled by oil companies, from the Gulf to the North Sea. In one you can spot gold glitter, settled like a sediment in a snowglobe; another reflects light shining in from the window, casting miniature rainbow refractions on the velvet. Six office-style paperworks surround the installation: rectangular, pillowy things with discrete rust stains and stencilled prints so faint they are almost invisible, held together with lines of paperclips mosaicked in colours inferentially referencing service ribbons and oil-related geopolitical conflicts. These works together act as the entry point to the Plymouth-born artist’s bold new show at London’s ICA, Morale Patch.

Morale Patch takes a somewhat frostier stance than Sasraku’s previous shows. Man Engine (2023) and Terratypes (2022) saw her present ‘terratypes’, hybrid collages made from sheets of newspaper sewn together and coloured with pigments foraged from British landscapes like Dartmoor, the Jurassic Coast and the Isle of Skye, as well as coastal Ghana, her father’s homeland. Morale Patch sees Sasraku taking a more explicit reckoning with geopolitical crises, connecting symbols of the US military and international oil industries with the human desire to memorialise, to leave a mark. Here, Sasraku looks at land as a system, a resource, while referencing the offices of the powers exploiting it. She spoke to ArtReview on the opening day at the ICA in London.

Soul Tan

AR Let’s start with the exhibition title, Morale Patch. Where does it come from?

TS The name refers to an object I’ve been collecting. A ‘morale patch’ is typically a small piece of unofficial insignia which military members will wear as a way to encourage morale within their group. I’ve also been collecting paperweights, which are issued to veterans of the oil industry. They’re both trinkets that try to attach meaning to industries that are often bound up in chaos.

AR The Subdued Morale Patch [2025] series uses sunbeds to make UV prints on the paper. How did that process work?

TS I’ve been trying to develop a new photographic process over the past couple of years and have worked with newsprint since 2018. It’s naturally light sensitive, so I knew I wouldn’t need to apply chemical medium to it, unlike traditional photographic practices. I just needed really strong UV and to place some sort of negative or stencil over the top. I thought: what’s the most concentrated form of UV? Sunbeds. I spent a lot of time as a child just staring at my mum glowing in tanning beds in Plymouth. I managed to get one from that time period. They really speak to the human desire for superficial beauty.

AR The stencilling effect is almost ghostly.

TS The exposure to UV activates the acid in the paper, so if you mask-off certain sections, parts of it darken. Photo-oxidation. At first, I thought it would be really vivid, but I would leave the studio and come back the next day, and it was gone. For each Subdued Morale Patch, I fixed 115 layers of blank newspaper with clips, soaked in a tub of water. All the paper swells, giving it a bulging and rippling across the surface. While that’s happening, the [front] image is being fixed.

Red Flags

AR Much of your previous work felt rural and organic; Morale Patch seems corporate and geometric.

TS I was interested in these works feeling a bit colder. Formally, the show is quite geometric. Previously I’d worked with figuration and I was using a lot of pattern cutting. Those works were very painterly, almost. I wanted to remove my hand from this show to find a new way to work. I was finding my practice really labour intensive, like it was destroying my body. As I lent into this more removed way of working, I felt like it spoke to the themes quite well.

AR Does this exhibition signal a shift away from a personal to a geopolitical outlook? Or are they inseparable?

TS It’s the same ideas I’d been working with previously: death, ambition, masculinity and the failure of all those things, applied to the global human story. Someone said to me a while ago that throughout your life as an artist, you will just keep making the same work. The more I look at the scope of my practice, I feel like that’s true. It just goes from micro to macro. We’ve all been absorbing so much militaristic rationale and violence through our phones over the past two years. Naturally, it’s become about asking: why is this violence being cosigned? What is underpinning all of that? I’m interested in the narrative power of organic materials, and oil revealed itself to be this missing puzzle piece in the story.

AR Your work incorporates symbolic objects – like ribbons and paperweights – as ‘found’ materials. You also take on the American flag in your larger paperwork, Allomother [2025].

TS That was me challenging myself, thinking about nationalistic symbols, colour association, and finding a new way to approach the American flag in the tradition of artists like Jasper Johns, Thornton Dial, William Pope.L. I think it often represents a point of confidence in an artist’s career, where they can take on an iconic, charged image. The American flag feels like it’s really up for grabs right now in terms of what direction it’s pulled in. To create one cobbled together out of office ephemera, marked but fading and changing… that’s a work I’m interested to see what its life will be like.

Toxic Tat

AR You’re now using found objects – the paperweights – which is new in your practice.

TS It was quite scary, to be honest, to have the show open with found objects. Coming out of my art-schooling experience, I didn’t think that I could do both: I thought you are someone that works with crafted things or found objects, and you can’t split your brain. But I feel really proud that I found a way to do both, because I’ve enjoyed being an artist a lot more since I’ve been thinking about objects. To keep challenging myself and not be pinned into any particular medium sparks a lot of joy and excitement.

AR The paperweights there have this strange cute-but-sinister feeling. How did you start collecting them?

TS You can find them in charity shops in Scotland, and if you search ‘crude oil’ on eBay, that’s what comes up. It seems there were a lot in circulation in the late 70s and mid-90s, and now people don’t really know what to do with them. They were made, typically, for people in managerial positions at oil companies about to end their career. But they were also issued to workers when new oil was struck. When oil was first found in the North Sea, off the coast of Aberdeen, it was such a huge moment for Britain’s status power that BP were like: we need to memorialise this through these trinkets. A lot of people list them as if they’re just their husband’s tat; other times, the seller understands they’re about to become a historicised object. The price range is quite interesting. You can find two of the same: one listed for a tenner, the other for £1,000. I’m really interested in how you value them.

AR People always want something tangible; a marker. Then there’s all of the connotations that come with the physicality of them. One is shaped like an hourglass.

TS I think that hourglass shape is my favourite. There’s a metaphor worked into them, which seems to be dealing with corporate time and deep time, simultaneously.

AR And the tension between the fact that they hold something toxic, but they’re also fragile. I have this desire to pick them up.

TS If you came across crude oil spilled on the ground, I don’t think it would incite the same kind of reaction that would draw you to it. But I think the way they’re contained in that blown-glass teardrop and then in this beautifully cast acrylic outer, with the screen printing and the presentation of them: they bring you into the impetus behind prospecting oil and extracting it, and this obsessive relationship that humans have developed with it, which is almost worshipful.

AR You’ve been very particular about how you displayed them: almost like a chess board.

TS I spent probably four months just trying to understand, formally, how they related to one another. After a while, it just wasn’t clicking. So I got them all out and started moving them around on my studio table. I was like: this is how it feels to move chess pieces. As soon as I turned their faces in, and realised they each needed their own square – some sort of a border that contained their sort of visual energy – it snowballed.

On identity

AR Much of the discourse around your work, especially in its earlier years, seems to be about how it relates to your identity. Does that manifest for you in Morale Patch?

TS I consciously made a point to try and depart from those narratives around my work back in 2020, when I took a break from film and started working on sculpture. It was to understand whether it was possible for me, as an artist whose identity had been really honed in on, to just be an artist. My identity – in terms of my racial identity, sexual and gender identity – is honestly something I’ve not thought consciously about for a while. However, I am very interested in looking at how masculine narratives shape our lives and how the feminine clads it, or protects it, or challenges it. In this show, that’s played out through the materials. The paperweights are quite hard and masculine, but then the velvet they sit on is like a soft carrier. Similarly with the paperworks, there is metal cladding a soft pillow.

AR There’s so much debate today about how art is supposedly overly burdened by identity politics. Do you think there is an expectation for artists now to elevate their identity within their practice?

TS I think there was that expectation in 2015, when I was starting on my BA. Massively. I would like to think that ten years on, people have gotten tired of it, but it’s hard to say. When I made a point of saying: I don’t want to talk about this, the artworld seemed to listen and respect that. I do think we have a choice.

AR The themes at play in Morale Patch are, on the surface, representative of the state of the world. There’s a lot of doom and gloom. Is there anywhere you can find hope?

TS I keep it open. I’m really not interested in moralising or making a didactic show, which requires a lot of preexisting research and understanding of toxic dynamics in our world. What it’s really about is the human desire to find meaning in times of chaos and violence, and that’s why I’m drawn to objects like morale patches and these corporate trinkets. It’s very human to make and accumulate these things. It’s been an explanation for me, rather than a lecture.

Tanoa Sasraku: Morale Patch is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, through 11 January 2026

Read next: How Joy Gregory’s art can be deeply political without being didactic