From 2010: Conceptually rigorous, seductive and unbounded, R.H. Quaytman’s paintings and silkscreens reflect upon the many ways in which we look at art – and ask us to use them all at once

In a radio interview in 1964, Frank Stella voiced a simple wish for his art: “All I want anyone to get out of my paintings, and all I ever get out of them, is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion”. A modest goal, no doubt, if at odds with the combative rhetoric surrounding his work: here was an artist, after all, who had finally driven the last of the Old World ghosts from American painting, eliminating space, image, symbol, emotion and all the rest, leaving a simplicity so simple it could only be expressed as a tautology. “What you see is what you see”, he said next. It was the quip that would be heard round the world.

R.H. Quaytman has applied herself with peculiar diligence to the task of disproving it, rerouting the direct line between seeing and understanding via strange loops and byways. Her work takes place within a history of similar critiques aimed at the irresistible target of High Modernism’s audacious self-confidence. It also suggests a way forward from this melancholy occupation, which has proven both generative and limiting for painting after the perceived end of the modern project.

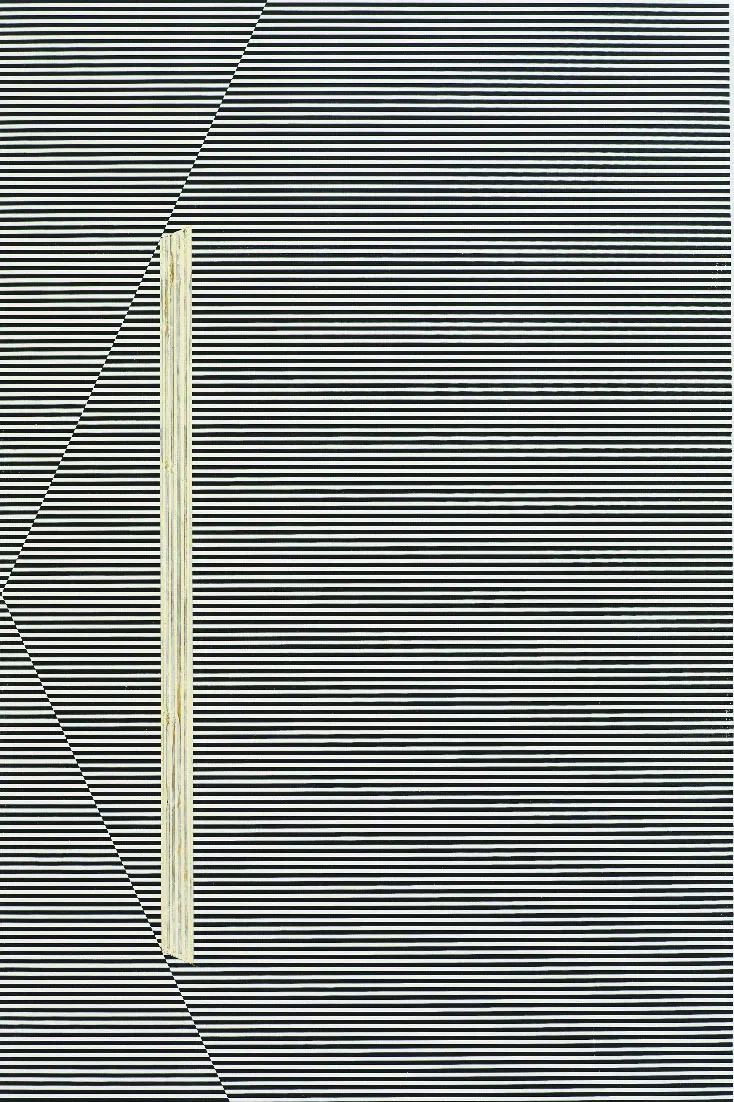

In her pursuit, the artist follows idiosyncratic but strict procedures. Shows are designated as ‘chapters’, suggesting an elaboration of themes in sequence; individual works function dialogically within the framework of each exhibition. Works are made either by silk-screening images onto gessoed wooden panels or rendering abstract pictograms by hand with an industrial paint called spinel black. Many paintings document features of the spaces in which they’re shown, deriving subject matter from the architectural, historical or financial details of their exhibition site; others borrow motifs from Op art. Often, Quaytman presents multiple versions of a motif, subjecting the same image to various photomechanical or digital interventions: rephotographing her own paintings under nonstandard light conditions; overlapping multiple silkscreens to achieve unusual colouristic effects; or stretching, cropping, inverting and layering source images in Photoshop. If the tradition of geometric painting that Quaytman gestures towards was best represented by a grid (all of its points reassuringly visible in one glance), then her work’s emblem is the picture-within-a-picture: a recursive set of nested images, each modifying – framing, illuminating, sometimes obscuring – the next.

For an artist who recently directed a gallery (the three-year cooperative project Orchard, on New York’s Lower East Side), this attention to the role of setting is no coincidence. In Chapter 12: iamb, her 2008 exhibition at Miguel Abreu Gallery in New York, Quaytman staged an encounter between a painting (a dense, optically active grid) and a lamp (a utilitarian office model), and presented the results as a visual essay on the vagaries of spectatorship. The lamp affixed its beam on the painting, creating a blown-out miniature sunspot on the surface of the image. The variations in the resulting works – differences in illumination, cropping and palette – seemed to model the viewer’s shifting perception of the work of art: from a foil for pure retinal stimulation, to a quotidian decorative object, to an elegy for the end of painting. Exhibition Guide, Chapter 15 (2009), her exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, resurrected motifs from abstract paintings in the museum’s collection, reproduced a manifesto published by the institute in 1948 and proudly adopted its palette from the garish pink of the museum’s signage.

But for all the strategies of conceptual art that organise Quaytman’s practice, just a few moments in the presence of the works themselves suggests another, contradictory interpretation: the artist is making unique, highly crafted aesthetic objects, visually seductive enough to turn Daniel Buren’s green stripes pale. This reading comes down, in large part, to the history of Quaytman’s materials. Silk-screening made its appearance in the art of Rauschenberg and Warhol as a bracing bit of nonart rudeness, ripped from the world of commercial printing to signify speed, iterability and impersonality. But as digital output processes have reset the goalposts for transgressive antipainting, the silkscreen is now positively redolent of care and intimacy – in 2010 it’s practically an Old World technique. Even the ‘diamond dust’ that occasionally appears in both Quaytman’s work and Warhol’s has been recast from a cheeky evocation of glitz to a sober memento of the physicality of images. These and other clues (like the queasy discord between moiré and pixelation produced when Quaytman’s more optical works are viewed as jpegs) suggest that the formal qualities of these paintings are meant to do more than allegorise an outmoded symbolic system.

In the Whitney Biennial, 2010, Quaytman presents a suite of paintings that move along similarly self-divided lines. The twin centres of Distracting Distance, Chapter 16 (2010) are two images of the artist K8 Hardy, posing nude with a cigarette in the gallery in which the works are installed. The tableau repeats Edward Hopper’s A Woman in the Sun (1961): Hardy is framed by one of the Whitney’s signature trapezoidal windows; in one of the two works, the same low leather bench that sits in the centre of the gallery protrudes from the right edge of the image. Elsewhere in the room, panels screened with tight radial lines mimic the receding plane of the window glass.

Here one has to remark on the very rarefied context in which these details are interpretable and significant. The art-institutional framework that Quaytman limns – its rules and mythos, the history of its internal debates – is not so much an object of critique as a magic circle in which paintings are made to speak again; what happens when the work steps outside its own conceptual boundaries is an open question. For now, to view these works is to be made aware of the grossly disparate mental activities we conventionally group under the heading ‘looking at art’: responding to optical phenomena, positioning our bodies in relation to objects in space, imagining other places and times, interpreting narratives and speculating on intentions. Leaping from one to another (for example, reconciling a meditation on Hopper, gender and sitespecificity with the adjacent painting that creates the experience of physical vertigo induced by two overlapping grids) feels like being reprogrammed for a new kind of viewing – one based on the exhilarating prospect that what you see is rarely what you see.

From the May 2010 issue of ArtReview – explore the archive.

Read next: The ‘Shitshow’ of Documenta 14