Will anything interesting come out of the copyright on Mickey Mouse expiring?

The first pornographic image I ever saw was a T-shirt displaying an erotic encounter between Mickey Mouse and Pinocchio. I grew up in a tourist destination, so I’ve seen a lot of bad T-shirts. Entire streets of the city are brimming with shops flogging detritus designed to appeal to anyone who passes through and the lowest common denominator is, of course, the minor god of branding: Disney. Mickey and Pinocchio make for unlikely husbands, and there was the slightly grotesque and bootleg quality to their features that signalled the design probably wasn’t sanctioned by Disney. But artists, T-shirt makers and common people can now rejoice – as of the first day of this year, that erotic T-shirt is half-legal (Pinocchio only enters the public domain in 2035). The mouse is out: Mickey is in the public domain.

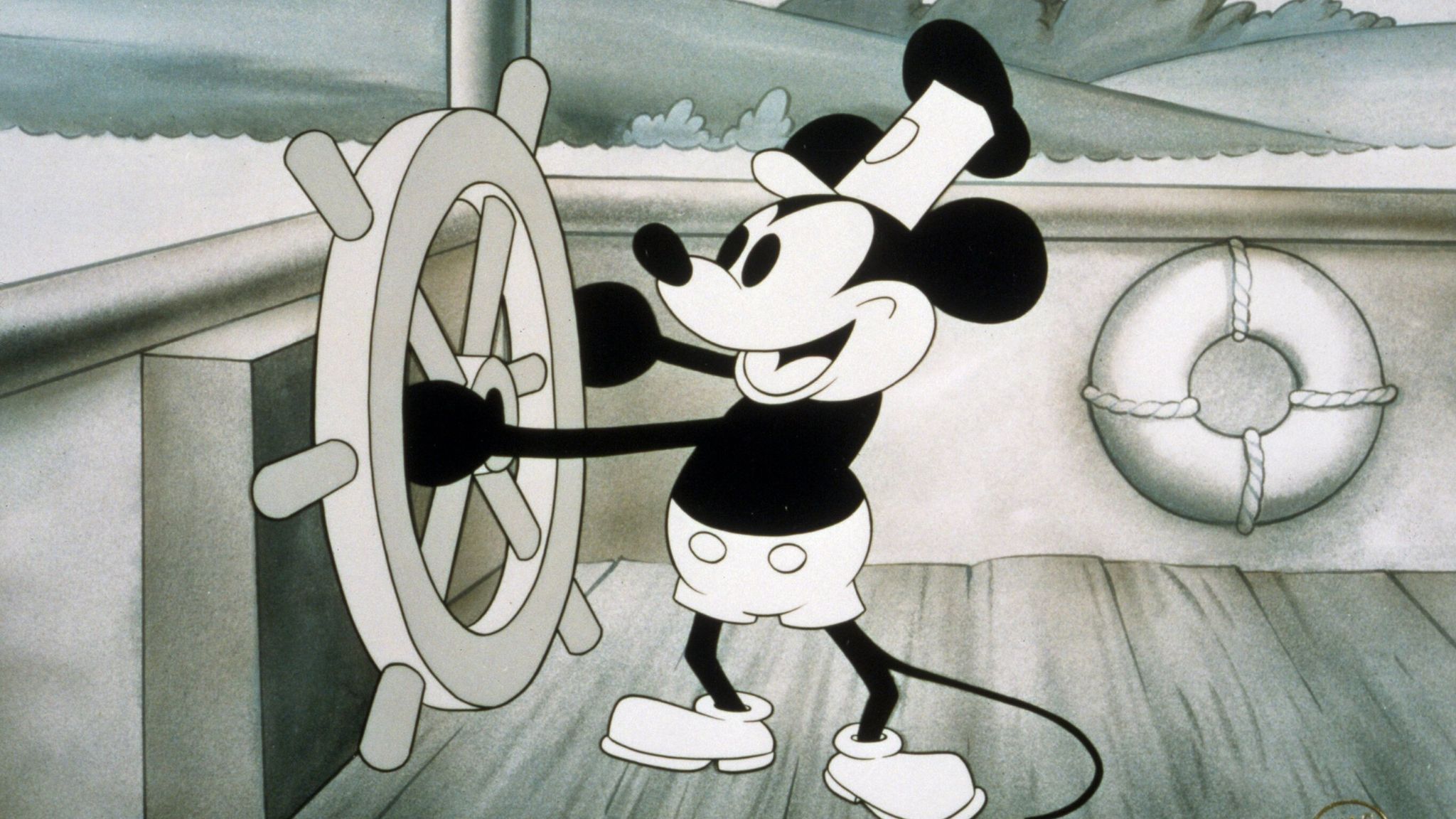

This release has been delayed. Mickey Mouse as depicted in his first appearance, Steamboat Willie (1928), was initially meant to enter public domain in 1983 and then in 2003, but on both occasions Disney successfully lobbied the US Congress to alter copyright laws so that the company could extend its hold on the mouse. These efforts were extremely expensive, but the possibility of losing Mickey’s image seemed a greater financial and existential threat. By 1983, the image and notion of Mickey was entirely interwoven with Disney’s brand identity, and losing control over his image would have been losing control over Disney’s image and, crucially, their merchandising income. The threat of the mouse entering public domain in 1983 also marked the fact that the rest of Disney’s characters were about to seep into public ownership at the same pace in which they’d been invented. Losing Mickey, one of their earliest characters, didn’t just represent a threat to the face of Disney, but also the beginning of an end. That Disney’s product was easily reproduceable and universally identifiable cartoons also posed a real problem – once in the public domain, any old chump could draw a facsimile of these characters in any configuration from the Kama Sutra and slap it on a T-shirt – legally. So the law had to change.

Copyright law is ostensibly designed to protect the intellectual property of creators and to offer them control over the distribution of their work. This is why copyright has always been in relationship with the measure of a lifetime; it is meant, by and large, to serve an individual creator. That the law did change wasn’t exclusively thanks to Disney’s work (its lobby was joined by several other corporations including Time Warner, Universal and Viacom) but it isn’t surprising that Disney spearheaded the campaign for the extension of copyright length. The blurring between Walt Disney (the man), Disney (the corporation) and Mickey (the face of it) goes in tandem with a company whose business model relies on children and nostalgia. It is unsavoury to be sold sentiment by someone who is actively selling you sentiment, so Disney defangs itself by posing as benevolent and human, a company that is the simple and innocent result of an old man’s dream to help make memories. After the second lobby, copyright was extended to last the artist’s lifetime plus 70 years, essentially a whole new lifetime’s worth of ownership – the measure of a human life replaced by the newer and better life: the corporation’s. But in the process Disney cemented itself as a symbol of corporate greed, capitalism and, regularly, America itself, rivalling only McDonalds in terms of this cultural symbolism. This is a price Disney was willing to pay – it could afford it.

Also in Disney’s favour is the fact that the more ubiquitous an image is, the less effective its use in satire, especially when the image has become interchangeable with a brand. Disney’s project in the last 20 years of borrowed copyright time has been to slowly elevate Steamboat Willie’s Mickey into this mythical figurehead of Disney’s origin story so any reference to him now is simply equivalent to advertising. So it has become almost impossible to successfully satirise Disney without implicitly reenforcing things we already know about the company or that they want us to believe: that Disney is synonymous with childhood and joy (this is a compliment to them), or that Disney is incredibly rich (everyone knows this and most people don’t care).

If it feels like a victory that we finally get free reign of Steamboat Willie Mickey, and therefore, in a way, Disney, it is difficult to imagine that this will matter. Bootleg pieces of Disney merch are already widely accessible, and art has used Mickey’s image before, either licensed by Disney or successfully exploiting the fair use exemption. This art is often disappointing and the satirical art is even worse. KAWS’s Companion sculptures ask the audacious question ‘what if Mickey Mouse looked a bit depressed?’, a concept that relies entirely on the irony that Mickey can’t be depressed because Mickey is happiness, and they also bear such a striking resemblance to Mickey, including the heavily and obsessively trademarked white gloves and shorts, that there is a real possibility they’ve been licenced by Disney, though this hasn’t been confirmed. Definitely not licensed by Disney, but equally reliant on bottom-drawer subversion is the 2013 horror film Escape from Tomorrow, which employed guerrilla tactics to be filmed entirely in Disneyland and is about a man losing his mind on his family holiday while simultaneously unearthing that Disney runs a sex trafficking network. The film was mostly panned, but the moxie it took to make it was admired. But perhaps the greatest failure in politically weaponising Mickey’s image is Banksy’s Napalm/Can’t Beat That Feeling (n.d.), which depicts Phan Thị Kim Phúc (also known as ‘the napalm girl’) cut out from Nick Ut’s photograph The Terror of War (1972), flanked now by Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald. It’s presumably a comment on America’s atrocities in the Vietnam War, but it is questionable how this artwork achieves anything darker, or more brutally condemnatory than the original photograph. Since the copyright lapsed a flurry of new material exploits Mickey’s now-public face, but most of it compounds the sense that little will change about art’s relationship with Disney. The horror films (and horror video game) aren’t likely to do any harm to Disney, though there is a charm to the fact that they can parasitically draw on Disney’s fame to elevate their own work, and that they can capitalise on this too.

The last 20 years have marked a phenomenal growth in Disney’s intellectual property. It’s swallowed Marvel, Lucasfilm (therefore the Star Wars franchise), Pixar and 21st Century Fox, among others, meaning that though Disney’s image is still deeply reliant on Mickey’s, it’s no longer as dependent on him as it was in in the 80s. And though Disney may have lost one specific Mickey, his image and every composite part (ears, shorts, gloves, silhouette and likely more) remain trademarked. (A trademark is distinct from copyright in that there is no time limit to a trademark, and its purposes are explicitly commercial). Without the copyright law on their side, Disney will now likely weaponise trademark law against any image of Steamboat Willie’s Mickey that flirts too hard with their commercial properties.

Mickey’s freedom is narrow. Steamboat Mickey’s is even narrower. Any product that uses the public Mickey image without making it clear that it is not created by Disney will face the threat of litigation. Yet again Disney will pioneer a new reality of copyright, and the remaining cultural and legal limits that will surround this Mickey will demonstrate how public the public domain really is. It may be very little. But this doesn’t diminish that it will be undeniably satisfying to see a T-shirt with 1928 Mickey making love to another 1928 Mickey (with a clear disclaimer that this shirt has not been sanctioned by Disney, of course). I would wear it with pride.

Aea Varfis-van Warmelo is a Greek-British writer and poet. Her poetry pamphlet, Intellectual Property, was published by the Goldsmiths CCA in 2024.