Vera Mey and Philippe Pirotte speak to ArtReview about their outlaw planning for this year’s edition

The Busan Biennale, which changed its name from the Busan International Contemporary Art Festival in 2001, has been taking place in the South Korean port city since the 1990s. Renowned as a space in which to be experimental or in which to test new ideas, the exhibition has developed something of a cultish following among those in the know, but it is now emerging onto a broader world stage. In this it’s helped by the fact that Busan has a long history of migration, world trade and cultural exchange. ArtReview caught up with independent curator Vera Mey, formerly part of the founding team at Singapore’s NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, and Philippe Pirotte, professor of art history (and former rector) at Frankfurt’s Städelschule, and adjunct senior curator at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), to find out more about their outlaw planning.

ArtReview What were your impressions of the potentials of the Busan Biennale prior to taking up your posts as artistic directors?

Philippe Pirotte I think one of the things that becomes apparent is that you’re a bit undercover. I think that’s a benefit of working on it. It’s always been a biennial that is appreciated by people who are so-called professionals or critics, but in spite of that, it’s not this big thing that everybody looks at. It’s also not expected to set trends. In that sense, we thought that it was pretty much a refuge from that type of logic.

AR Do you think that the biennial format has become formulaic?

Vera Mey There are certain expectations around what it should be and how it should function and who should be included. I think we wanted to approach it much more openly: to think about contemporary art in a really expansive way, not just as people on the circuit.

AR Your theme for the biennial is Seeing in the Dark – a topic that some might say doesn’t present the most positive image of Korea…

VM We like the possibility of what it might mean, the idea of it being a visual paradox: to see in the dark. It also relates to the way in which people are talking about this contemporary moment, politically and socially: it’s a dark and gloomy time. We were interested in thinking about systems of knowledge and of being that don’t rely on the Enlightenment-era demand for transparency and clarity, and visuality, and how such concepts might reshape our understanding of images in a way that allows us to think about seeing in the dark.

PP It’s also about those people who are not seen, who remain in the dark. They remain in the dark because they are criminalised by their mere being. I think that’s a part of our biennale – this idea that, in the end, everybody gets criminalised, even if they haven’t committed a crime.

VM We were very much inspired by the work of David Graeber, the late anarchist anthropologist.

AR The work of his widow, Nika Dubrovsky, has been included in the show.

VM Yes. We were particularly interested in his posthumously published book Pirate Enlightenment [2023]. Pirates obviously have this history of being seafaring criminals; what’s interesting about the book is that it also tries to understand the position and perspective of pirates in relation to their resourcefulness, and as people who are marginalised or criminalised for various political and social reasons.

AR That might be a geographically specific interpretation though. A lot of pirates from Britain or the Gulf, for example, were state-funded.

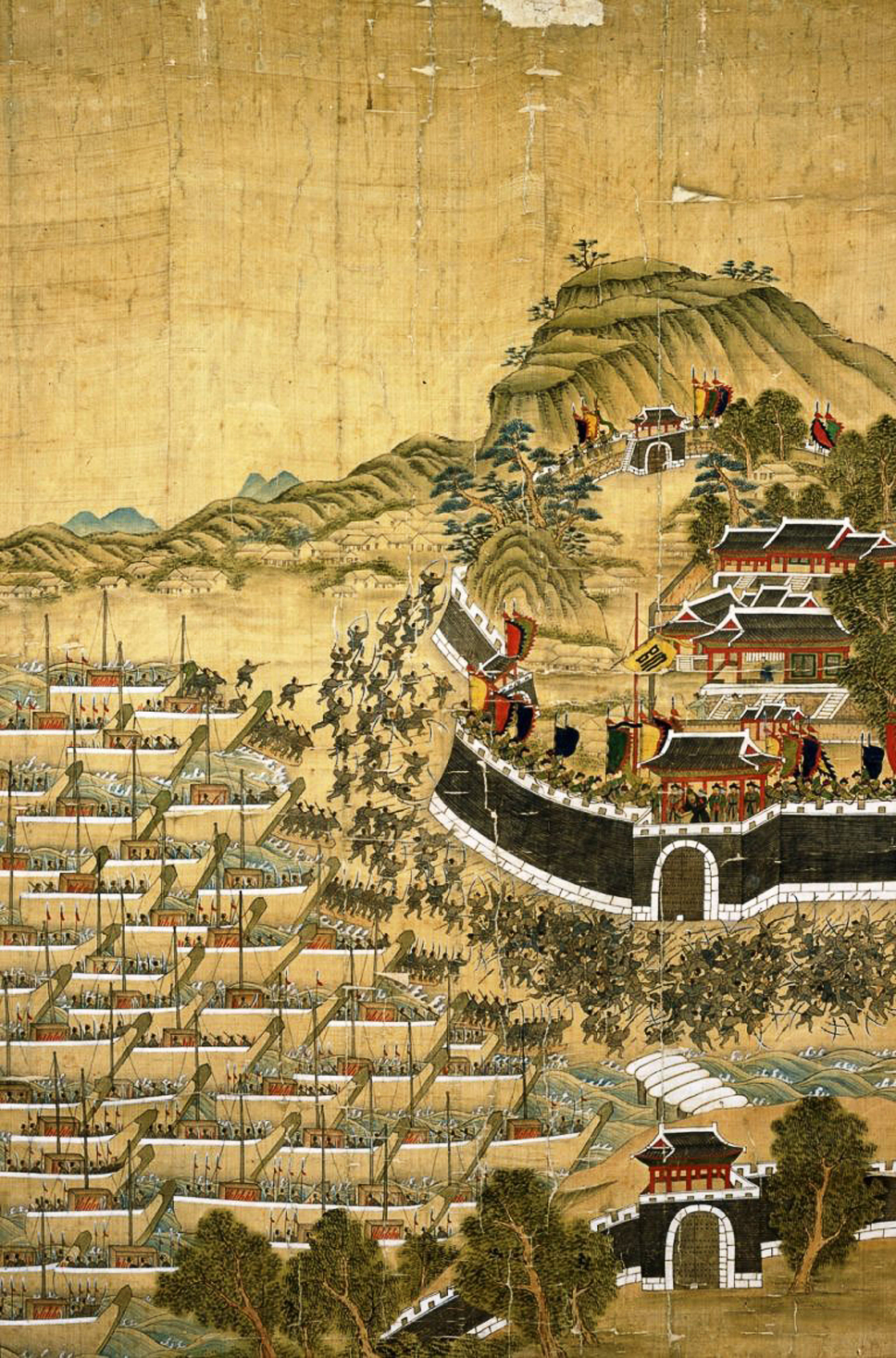

VM That fluidity and ambiguity of this status is something we’re quite interested in. Another aspect we were interested in with regards to pirates is that historically crews were often made up of very different communities of people: exiles, freed slaves, refugees, migrants, opportunists, traders. Busan itself is interesting because it’s a port city. They have a history of a community who were considered to be pirates, made up of Chinese, Japanese and Korean exiles.

PP It’s not about romanticising pirates. Our idea is that you become a pirate by default, because you’re fighting a bigger system or you are the victim of a bigger system. Maybe today that system is not geopolitics, but more like global incorporated business. I think the pirate is also a mirror. The criminality projected onto the pirate is somehow mimetic behaviour of the world’s corporate structures.

AR Do you see pirates and artists as somewhat analogous?

VM We do in certain respects. As part of our research, we also looked at what we call ‘alternative’ enlightenment movements. Not just pirate enlightenment, but obviously Buddhist enlightenment, which is very important in Korea, and what’s called ‘fugitive’ enlightenment, about which there is a lot of writing, which is a position of fluidity, which is both subject to the system, but also a mechanism to work around it.

AR I’m curious about how this became a working model for a biennial given that in no way is the Busan Biennale fugitive, in the common sense: it’s a fixture, a part of the establishment. You’re talking about positions – held by those who operate outside of such systems – that you’re going to corrupt in the very act of speaking about them, because once you’ve identified these people, brought them into the system, so to speak, they no longer belong to that fringe or the underground.

VM Completely. Obviously, staying within the context of a refuge is something that conceptually we’ve thought about a lot in relation to the ideas we’re exploring. What we are doing is something that is not in the refuge. So how do you negotiate the two?

PP I think a biennial cannot be more than a disparate allegory.

VM Yes, unfortunately – and also aesthetic strategies. We really operate in the realm of metaphor in some respects. There are various aesthetic strategies we’re drawing upon to think about darkness. One of them is the exhibition design itself: aspects of darkness and the surrendering of your senses; an experience that disorientates you, rather than satisfies your demand to know everything about the artists, artworks and objects, to see everything clearly. Maybe there are also some experiences we have planned that intend to disrupt the way that we see and perceive.

PP We have a very dark venue, which is the vault of a bank. It’s where all the assets are kept, also in the dark. This is not a transparent structure. There is a double-sided element to it. I think it’s important to say that in terms of a more anarchist strategy, we don’t have the ambition to change everything. We know that’s impossible. It’s more like we have inserted little grains of sand into the machine for our fun and survival.

AR It sounds like it’s probably a game of assertion and denial, right?

PP Yes.

AR Are there specific things about the art scene in Korea that inspired you when you were formulating your ideas?

PP One of the interesting things was meeting some artists from the older generation who have been, in a very interesting way, staying true to a particular working practice over a long period of time. Which is very different from the attention economy of today. It’s a studio practice. I think that’s very interesting: they have this idea that we go to the studio and we make work. We have invited some of these artists, like Yun Suknam, who is eighty-five. She started making art after she turned forty. It’s a very committed practice.

VM I guess we’re interested in the ways that artistic practices not only subvert the demands of that attention economy but also figure out ways to survive beyond it.

AR Is that where some of the Buddhist enlightenment material comes in?

VM In some ways we see Buddhist enlightenment as analogous to pirate enlightenment. This idea of focusing on a diasporic wanderer, someone who has to discern between reality and what’s not real.

AR Do you think it’s an optimistic biennial?

PP Let’s say it’s more a case of critical apprehension. It’s very image-driven, with an attention to analog artmaking, because, of course, Korea is very much looking into digital possibilities now, but that aspect will also be present in the show.

Busan Biennale 2024, Seeing in the Dark is on view through 20 October

This interview features in the ArtReview Korea Supplement, a special publication celebrating contemporary Korean art, supported by Korea Arts Management Service