The pioneering photographer’s documentation of discrimination, violence and a system that forced compliance, presages today’s prison industrial complex

There’s no doubt that the exhibition of photographs by Gordon Parks documenting segregation in 1950s Alabama and the US Black Muslim movement of the early 1960s at Alison Jacques Gallery in London’s genteel Fitzrovia has taken on added relevance in the context of the recent Black Lives Matter protests and the self-isolation (which at times seems like it might slip into various forms of segregation) imposed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The exhibition is an absolute gimme for an art critic (or gallery) wishing to assert their awareness of societal struggles surrounding race, inequality and the systemic suppression of peoples considered other. This past weekend The Sunday Times art critic Waldemar Januszczak dutifully (if clumsily) opened up his review of the show by remarking that he could feel ‘a powerful wind blowing across the land’. ‘It could be the wind of change…’ he continued, presumably channelling memories of rocking to The Scorpions and the events of 1989. ‘What it certainly is is the wind of pertinence,’ he went on, starting to row back, to hedge his bets, before noting that ‘the most important and best art being made right now is being made by black artists’ (no further details given) and that it had been an effort not to ‘blub’ once he had encountered Parks’s works.

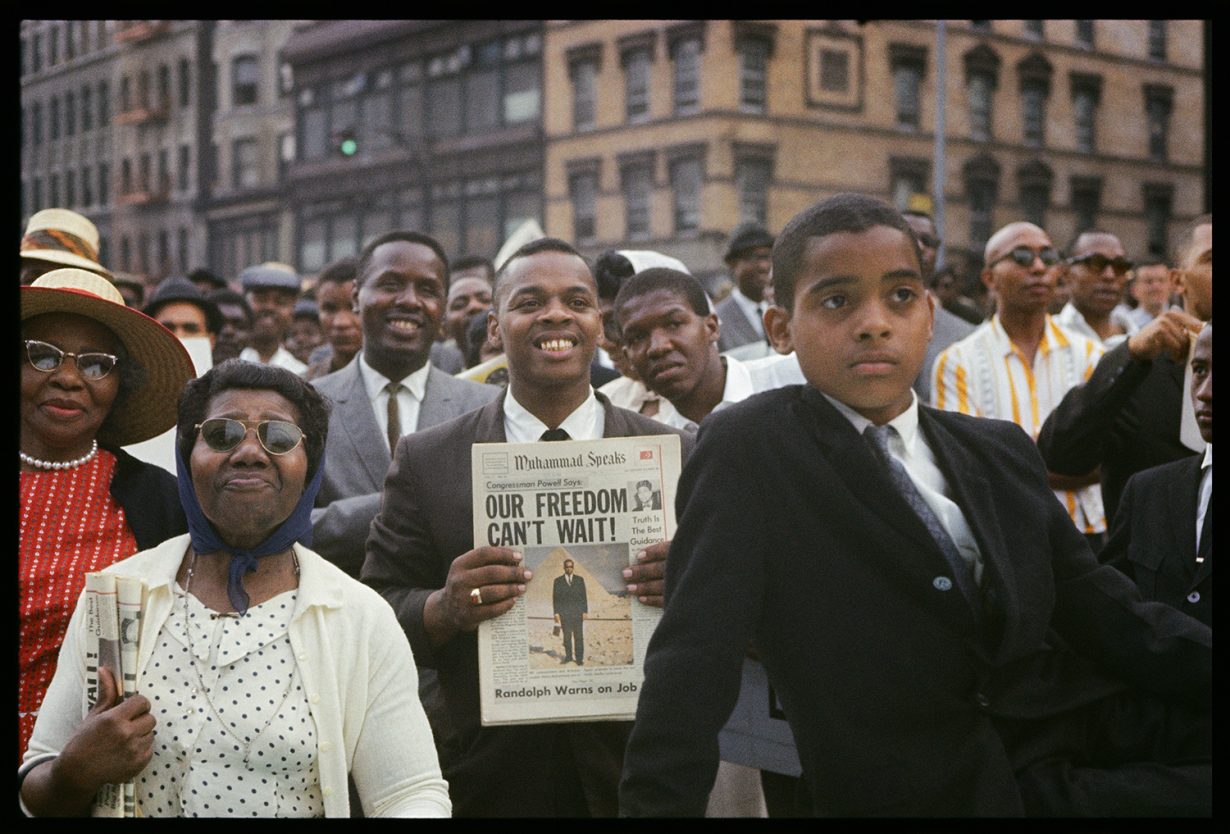

Parks, who died in 2006, was a photographer, writer, musician and filmmaker. The first African American to direct a major Hollywood movie (The Learning Tree, 1969, which was based on his own novel, from 1963), he went on to inspire a new genre (blaxploitation) with the release of Shaft in 1971. He first rose to prominence, however, as a photographer, originally working for the Farm Security Administration photography project, based in Washington, DC. The photographs on show in London were commissioned as stories for Life magazine: Segregation in the South in 1956 and Black Muslims in 1963. Despite Januszczak’s highly attuned sensitivity to shifts in the weather, they were as ‘pertinent’ then, if not more so, when they described the lived reality of their subjects. There’s no doubt that part of the point of Parks’s colour photographs of the segregated South and black-and-white portraits of Malcolm X was to document and assist the whipping up of a wind.

Simultaneously with the exhibition, Steidl has published The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957, documenting another of Parks’s series for Life (the photographs themselves are now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York). Parks was the first African American to hold the position of staff photographer (from 1948 to 1972) at the influential weekly magazine. The book documents his contribution to the 9 September 1957 edition of the magazine, titled ‘Crime in the U.S.’, featuring first the photographs themselves and then reproductions of the pages on which they originally appeared. The cover illustration, ‘A New York Street Gang’, looks like a scene from West Side Story (the first Broadway production of which opened later that month), suggesting the feature’s status as standing somewhere between reporting and entertainment. ‘On the surface, the world of crime is much like the world of honest men…,’ the Chandleresque text that introduces Parks’s contribution begins. ‘But underneath, this world has its own dark atmosphere.’ Sandwiched among adverts for Haggar Slacks, Bayer Aspirin, Metropolitan Life Insurance, Band-Aid plastic plasters, Gleem toothpaste, Fitch dandruff remover shampoo and Ford’s Edsel automobiles, there’s a sense of the feature titillatingly lifting the curtain on a life that Life’s largely white, middle-class, urban and suburban readers do not know. It’s no great stretch to imagine that a white-cube commercial art gallery opposite a posh hotel in gentrified London offers a similar audience a similar service today. Though it is also good, of course, that Parks’s work is being seen – this is the first solo exhibition of his work in the British capital in 25 years.

Back in the book, a blurry nighttime shot of a group of men hanging out on a street corner is captioned, ‘A furtive poker game whiles away a hot summer night on a tough sidewalk in New York. The beat cop has just passed, and the youths have time for a few more hands before he returns to break up the illegal game.’ Given that it’s hard to tell what exactly is going on, Parks’s image gently suggests a conflation of suspiciousness and crime, boredom and crime, a lack of places to go and crime. There are images of the aftermath of crimes – people being taken into ambulances, rooms being searched, but no images of crimes themselves (albeit the images not used by Life include a sequence showing a man shooting up – his arms at the moment of injection neatly mirroring other images of men’s arms in handcuffs).

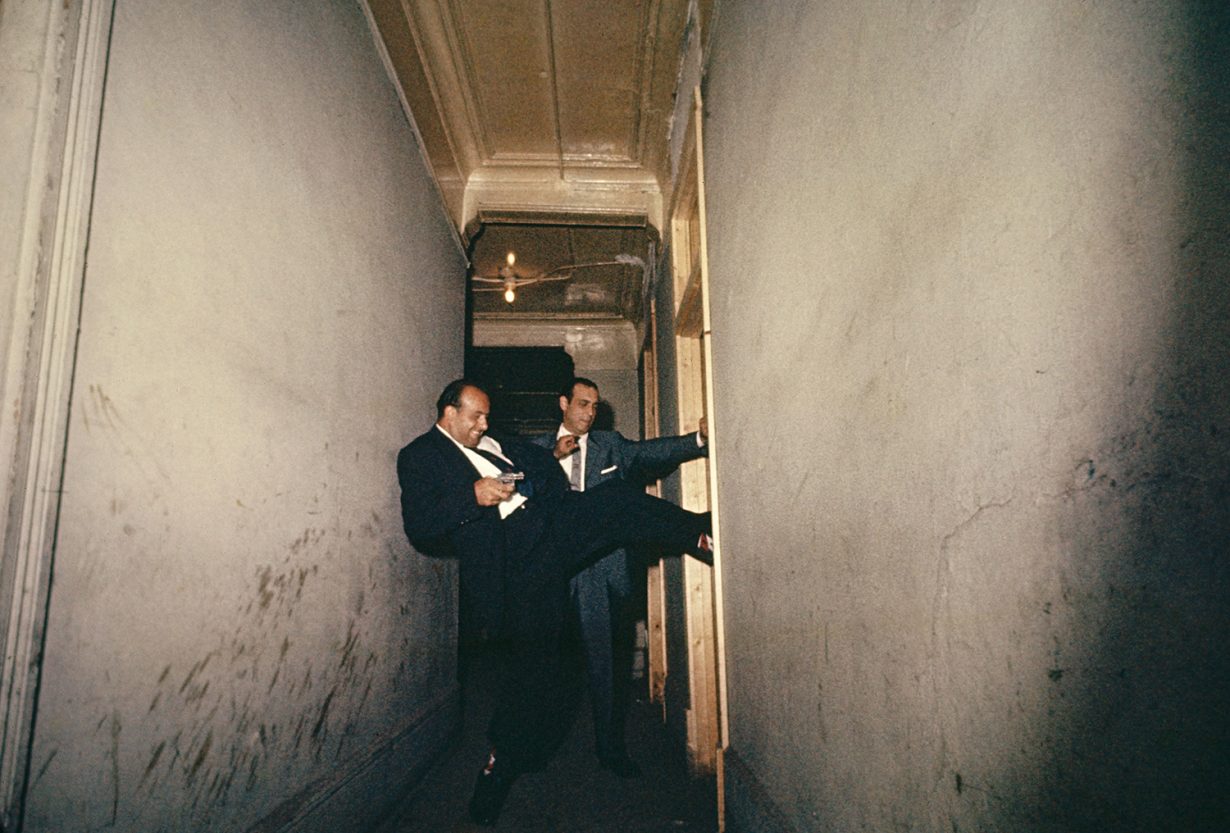

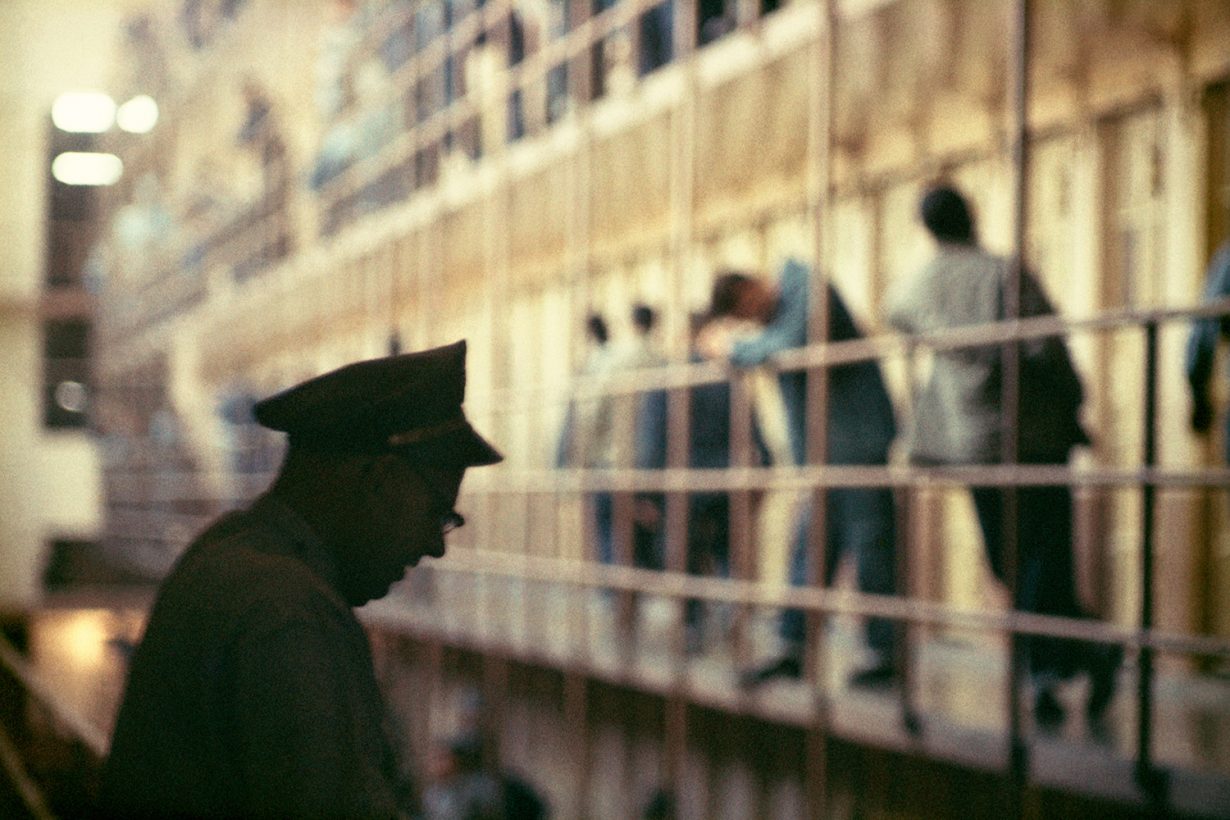

Taken on their own, Parks’s photographs document a world of poverty, drug addiction and violence, the last being more apparent in images of cops gleefully kicking down doors and brandishing revolvers than in any ‘criminal’ acts. ‘Guns drawn, Chicago detectives break in the door of a suspicious room. Surprise means safety. A quick kick follows a perfunctory knock,’ reads the caption (presumably written by reporter Henry Suydam, who worked with Parks on the assignment) that accompanies one of the photographer’s more dramatic images. When they’re not breaking in, the cops in Parks’s images are booking in criminals, doing paperwork, hanging around and looking out for suspicious rooms and people. Policework, as Parks records it, is a matter of bureaucracy, a symptom of a system. The Life feature ends with a shot of prisoners going into lockdown in San Quentin, a burly guard dominating the foreground.

According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a shocking one in every three Black males born today in the US can expect, at some point, to join the prison population, which has itself increased by over 700 percent since 1970. (The figures for Latino males are one in every six, and for whites, one in every 17.) These days US prisons are part of an $80-billion industry, with the prison phone industry alone raking in $1.2b of that. There are even dedicated prison trade fairs. It is, as Roger Ross Williams’s 2018 documentary Jailed in America (more pointedly titled American Jail for those of you looking it up in the US) argues, an industry that has become too big to fail. It’s an industry that, in nascent form, Parks seems to have identified in The Atmosphere of Crime (a subject further explored in essays by Nicole R. Fleetwood, Sarah Hermanson Meister and Bryan Stevenson in the Steidl publication).

Like Parks, Williams is something of a pioneer, being the first African-American director to win an Academy Award (for Music for Prudence, 2009, best documentary short). In a sense, Jailed in America feels like an extension of the sensibilities and some of the methods that Parks deployed in his own work, documenting personal stories (in this case the imprisonment and subsequent suicide of one of Williams’s childhood friends) and the expansive bureaucratic system that leads young African Americans to jail and then keeps them there as the levers of power are used to grease the cogs of an industry that in turn supports those invested in maintaining their power.

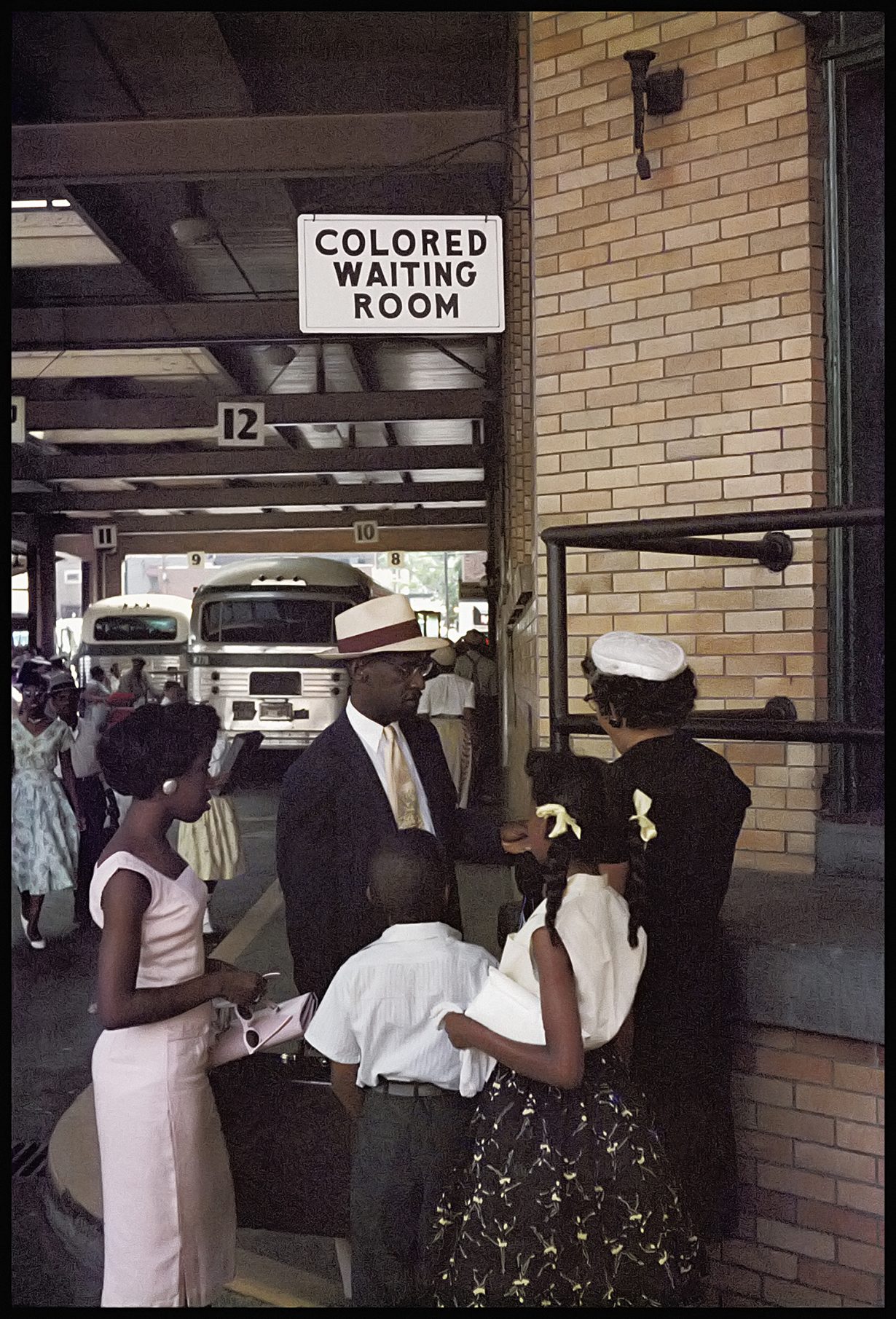

That discrimination and violence are woven into the fabric of US society is something that Parks’s photographs of Black life in the South amply demonstrate. As with The Atmosphere of Crime, his Alabama photographs document scenes that are apparently ordinary and everyday: people sitting on porches, people talking to neighbours, people buying ice cream. Yet the bodies are Black, the houses are rundown and the ice-cream shoppers are standing at the ‘Colored’ window or drinking from the ‘Colored Only’ water fountain. What’s remarkable is the dignity apparent in the three families Parks shot. The fact that they seem to be getting on with their lives despite the restrictions on how they are permitted to do that. A form of quiet resistance that seems all the more obvious when paired with the photographs from the Black Muslims series, which in itself attempts to record its subjects as a community as much as a movement or an existential threat to the US. What seems most remarkable now is that anyone put up with the shit that Parks recorded in Alabama. But flick back to The Atmosphere of Crime or open a newspaper today and you better understand the system that forced this compliance. And continues, in various less visible forms, to do the same today.

Gordon Parks: Part One is on show at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, until 1 August. Gordon Parks: Part Two will run from 1 September to 1 October. Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 is copublished by Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, in collaboration with MoMA ($40, hardcover)