From his landmark study of LA’s ‘carceral urbanism’ to a history of the car bomb, Davis bent orthodoxies in discipline-defining ways

In ‘The Poverty of Theory’ (1978), EP Thompson’s polemic against the philosopher Louis Althusser, he derided the intellectual snobbery of academic left circles – a state of affairs that, he wrote, ‘allows the aspirant academic to engage in a harmless revolutionary psycho-drama, while at the same time pursuing a reputable and conventional intellectual career’.

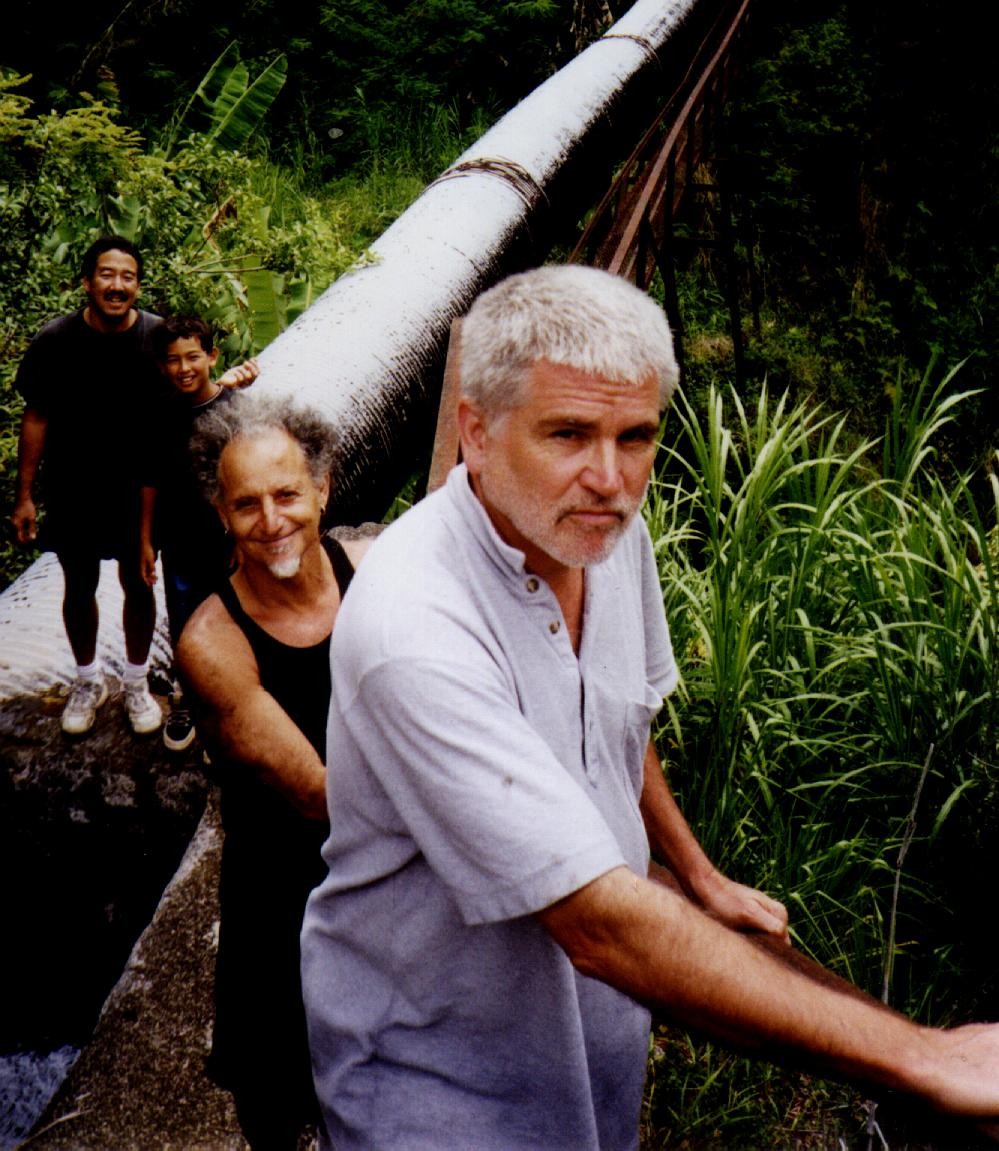

Mike Davis, who died at the age of 76 last week, was no such elite intellectual. Arguably one of the most important Marxist thinkers of the past century, Davis’s politicisation – and consequently his entire body of work – was shaped by collective material struggle. Born into a working-class family in southern California, Davis was a committed radical, who also happened to be an intellectual. Socialist historian, critical urbanist, geographer, and ecologist, he was able to perfectly fuse theory that emerged out of a very real world and an actual, existing working class – with praxis.

Davis focused on countering the hegemonic, dominant capitalist ideology from the broad to the granular. His body of work shunned ego and always led with and centred the collective, the working class, the ordinary people of the world – confronting the problem of atomization and the creation of the atomized neoliberal individual.

He referred to the six years he spent working as an editor at New Left Review in London in the 1980s as ‘some of the worst years of my life’, not being able to get along with the Etonian clique who presided over the journal at the time. ‘Ultimately you couldn’t really understand these guys unless you’d taken showers with them when you were ten’, he said.

Instead, Davis’s formative political experiences came through joining the US Communist Party and the labour organizing he was exposed to while working as a truck driver. He started, but never completed, a doctorate in history at UCLA. An unapologetic anti-imperialist, Davis was extremely active in the antiwar movement in the US, always thinking through the effects of US imperialism abroad rather than merely focusing on domestic struggles – a dynamic explored in his later intellectual work.

Davis centred the US military and police apparatuses in his critiques. ‘A simple slogan: US out, now and forever’, he said in a 2018 interview with Monthly Review, where he showed his deep-seated internationalism and his solidarity with victims of the US war machine from Iraq to Palestine to Libya, setting himself apart from other historians from the Anglosphere.

In his 2007 book, Buda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb, published at a time when ideas of ‘Islamic terrorism’ ran rampant, Davis instead chose to place what he called the ‘poor man’s airforce’ in a history that stretched from Italian anarchism to countering Israeli terrorism and post-US-invasion Iraq. The car bomb thus becomes a dangerous byproduct of asymmetrical warfare, rather than some wildly irrational strategy.

What made his writing resonate universally was that it was entirely unbounded, not in the placid interdisciplinarity that is boxed off and sold to universities, but true unboundedness that was able to completely alter worldviews. He took entire orthodoxies and bent them in ways that defined and defied discipline, while seamlessly tying them all together. Reading across his writing, you begin to comprehend how the struggles of a slum dweller in Manila might be tied up with the ordeal of being a tenant in Los Angeles, situated within the wider ecology and uneven development of the world. In his ambitious Planet of Slums (2005), a global survey of poverty and displacement, Davis showed us exactly this: he drew links between global capitalist development and rapid urbanization with the displacement of the urbanized proletariat and their expulsion from the formal world economy.

Davis also pioneered a distinct understanding of global poverty and ecological disasters. In Late Victorian Holocausts (2000), he explained that natural disasters like famines aren’t so much natural as the consequences of global capital accumulation through colonialism and imperialist expansion. In doing so, Davis was able to frame millions of deaths as avoidable – rather than inevitable – political tragedies. He was able to situate poverty in a relational dynamic to wealth, describing it as a systematic process of impoverishment rather than a state of being. He showed us that poverty is something some people do to others.

And no one understood a city better than he understood LA. In his landmark book City of Quartz (1990), a masterclass of historical geography and critical urbanism, he introduced us to the city’s processes of ‘spatial apartheid’ and ‘carceral urbanism’. Arguably one the greatest books of historical geography ever written, it is a truly masterful and holistic depiction of a city – and required reading for anyone who seeks to understand the process and consequences of suburbanization.

Davis’s principles would often get in the way of social niceties. In ‘The Case for Letting Malibu Burn’, the incendiary chapter from his follow-up to City of Quartz, 1998’s Ecology of Fear, Davis provocatively argued that the broader public purse should not have to go towards rebuilding or protecting mansions for the rich in the face of climate catastrophe, at the expense of ordinary people.

Referred to frequently – and erroneously – as the prophet of doom, for how often his predictions proved to be correct, Davis actually embodied a radical optimism even in the face of hopelessness. His work always searched for radical human possibilities; his polemics were powered by rightful rage, rather than cynicism or despair, written out of a radical love for and an unshakeable belief in ordinary people, and their potential to exact change.

He pushed for the adoption of ‘utopian’ thinking even in the face of the bleakest realities. ‘“Hope” is not a scientific category. Nor is it a necessary obligation in polemical writing. On the other hand, intellectual honesty is and I try to call it as I see it, however wrongheaded my ideas and analyses may be,’ he said in an interview in 2016. ‘I manifestly do believe that we have arrived at a ‘final conflict’ that will decide the survival of a large part of poor humanity over the next half-century. Against this future, we must fight like the Red Army in the rubble of Stalingrad. Fight with hope, fight without hope, but fight absolutely.’

‘Writing was the hardest thing I ever learned to do,’ he told the Guardian this year. And yet he understood the necessity and had the commitment to write, and write prolifically. His influence on how to analyse our world, and to change it, was extraordinary.