From an experimental film festival in London to the Busan Sea Art Festival, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Experimenta

BFI London Film Festival, 4–15 October

Bereft of Hollywood stars on the carpet due to ongoing SAG-AFTRA industrial action, London Film Festival this year promises to be a more focused affair – and, as such, more room might be afforded to the BFI’s Experimenta program. The ghettoising of ‘experimental’ cinema into subcategories – and the communities to whose films such taxonomy often applies – can frustrate, and yet there is much here to celebrate. John Torres’s Room in a Crowd collages fragments of stories in the context of state oppression in the Philippines; Karrabing Film Collective will screen Night Fishing with Ancestors in concordance with their opening at Goldsmiths CCA. On 14 October, Fox Maxy’s Gush will show at ICA, a 10-year personal history of land and body whose fluid aesthetic combines lofi mediums and hallucinogenic colouring, all with a Sundance Institute Indigenous Program budget of US$1250. A week prior, Martin Scorcese’s Killers of the Flower Moon will grace the main LFF program – US$200 million; three-and-a-half hours long; charting the investigation into murders of Osage tribe members in the 1920s. For a sense of the scope and challenge cinema can present, there can be few better examples. Alexander Leissle

Avery Singer: Free Fall

Hauser & Wirth, London, 11 October–22 December

Memories can be as sharp as they are slippery. And when it comes to collective memories and experiences of a traumatic event, they can become altogether more amorphous. For her first solo exhibition in the UK, American artist Avery Singer addresses this by first mining her own memories in order to physically reconstruct the interior spaces of the World Trade Center’s North and South Towers prior to their destruction by terrorist attack in 2001. As a child, Singer was a frequent visitor to the towers in which her mother worked; she was 14 when she witnessed the towers crumble. Punctuating the architectural intervention into the gallery space – with references to the towers’ windowless corridors, lobby spaces and slit windows, reflecting the ‘banalities of office life’ – will be a new series of paintings that depict both her own memories of the aftermath (of seeing debris, injured victims and severed body parts), as well as recreations of images (of survivors and of the disaster site) she remembers from media coverage at the time. Singer has long used computer technology in her work in order to erase ‘the trace of her own hand’; it seems apt, then, to employ this for Free Fall, wherein the subjects of the artist’s series of paintings are created with modelling programmes and digital airbrushing, among other computational techniques – resulting in a body of work that distances the artist and at the same time realises the nebulous quality of shared trauma. Fi Churchman

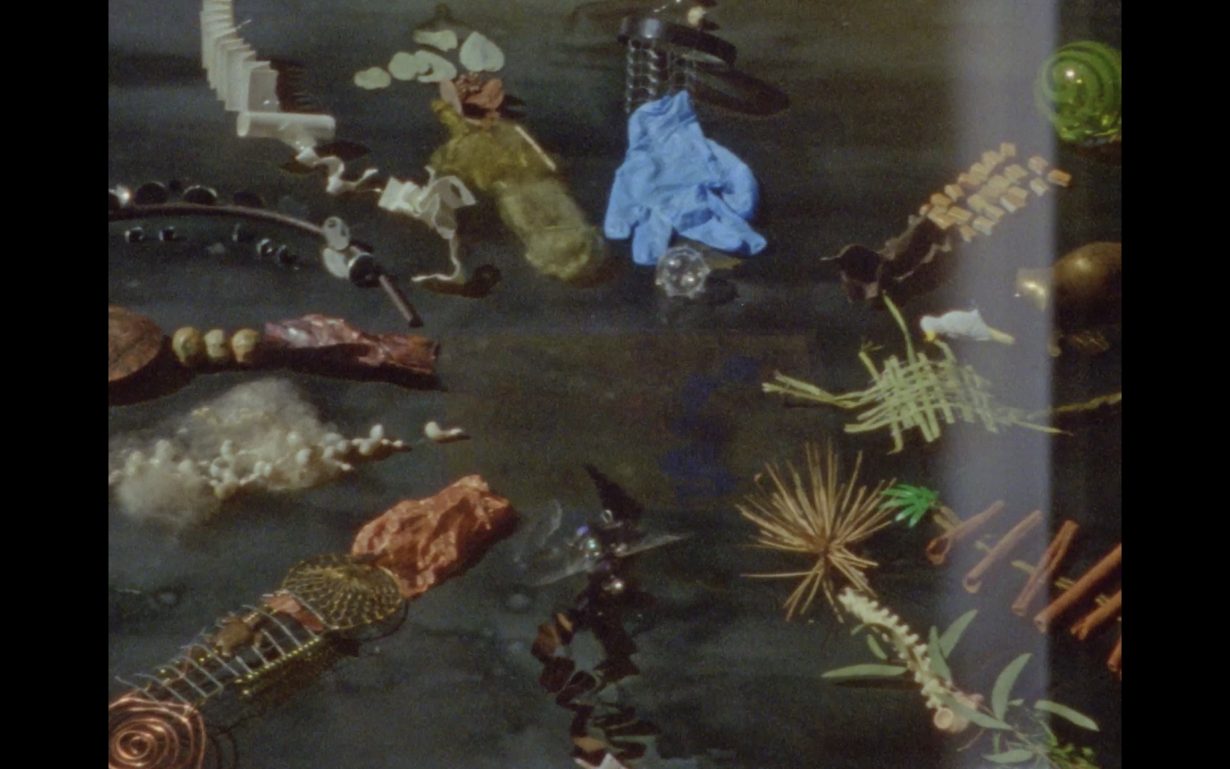

Tamara Henderson: Green in the Grooves

Camden Art Centre, London, 6 October–31 December

The first solo institutional exhibition in the UK for Henderson, Green in the Groves presents a new body of work Henderson has been developing for three years, which will include sculpture, installation, painting, live performance and film. Henderson, a Canadian artist based in London who makes anthropomorphic sculptures and designs costumes for them, creates projects that fuse narrative, objects and performance. The figures, sets and costumes in her stories all cohere to speak of certain themes. For example, friendship in The Syzygy of Cinnamon at The Intermission in Piraeus in 2023: Syzygy comes from the Greek and means ‘conjunction, yoked together’ and is often used in astronomy to describe the relationship of the moon and the sun. Seasons End (2016–18), performed at Serpentine Park Nights and displayed at Glasgow International, REDCAT in Los Angeles and Oakville Galleries outside Toronto, was a multifigure dreamlike consequence that honed in on different characters at each iteration. This new show turns its gaze underground – to the earth itself, exploring life beneath the surface in a new film; a series of 12 paintings; ceramic, glass and bronze sculptures; a sound installation and bespoke costumes for each of the characters Henderson invents. Orit Gat

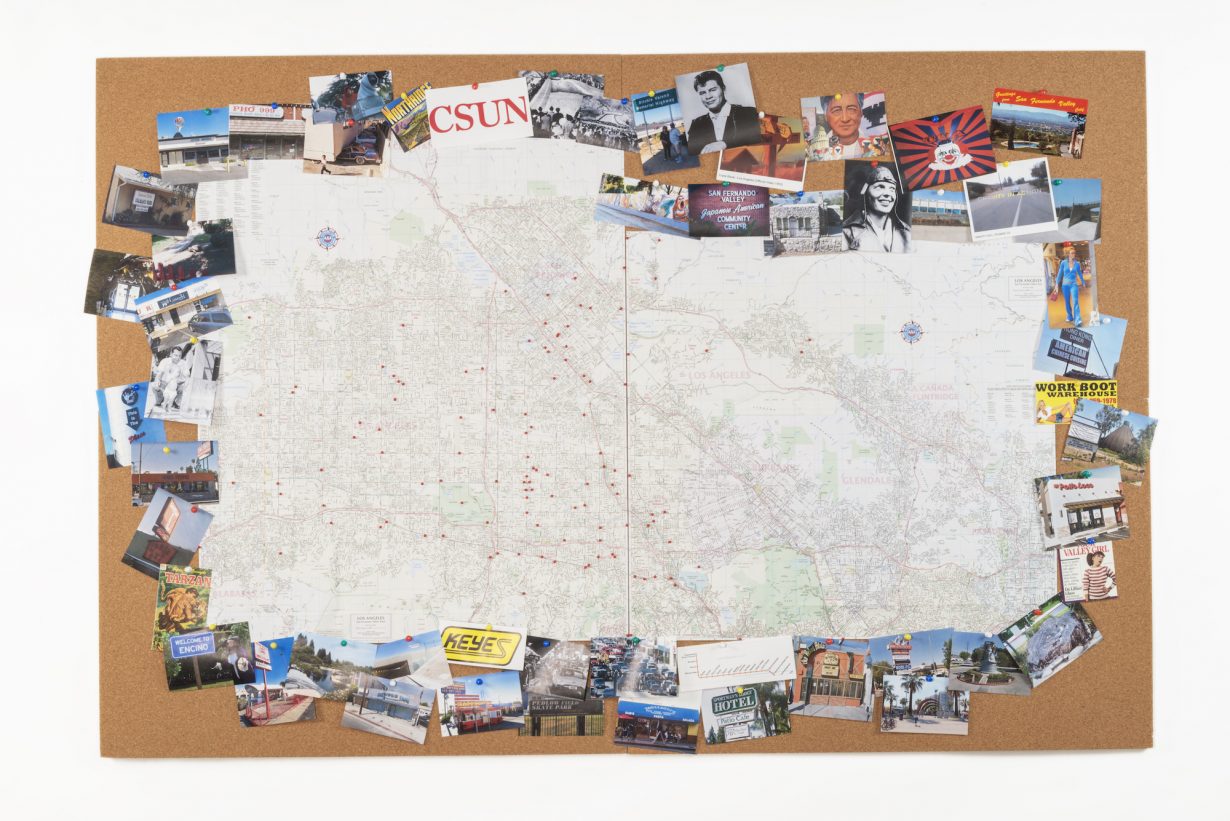

Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 1 October–31 December

As Tupac once intoned in his song ‘California Love’, “In the city of good ol’ Watts… we keep it rockin”. California, and in particular Los Angeles, has captured international imagination for decades, its romanticisation in part owing to the glamour of Hollywood and the city’s sunny blue skies. Like its preceding editions, this year’s Hammer biennial looks to artists who have been ‘Made in LA’, and who can fill in the gaps between romanticised notions of the sunny coastal city. This sixth edition takes its name from a plaque at Watt’s Towers that quotes the artist, Noah Purifoy: ‘Creativity can be an act of living, a way of life, and a formula for doing the right thing’. Thirty-nine artists, collectives and organisations from greater Los Angeles will be ‘rockin’ it as they demonstrate that life and art are inseparable with mostly new works that span different mediums, cultural and generational experiences. And while Acts of Living will undoubtedly consider the complexities of the sprawling urban landscape, the artists will reflect on the city they’ve made home affectionately because, to again quote Tupac, ‘Only in Cali where we riot, not rally, to live and die / In L.A. we wearin’ Chucks, not Ballys (Yeah, that’s right)’. Marv Recinto

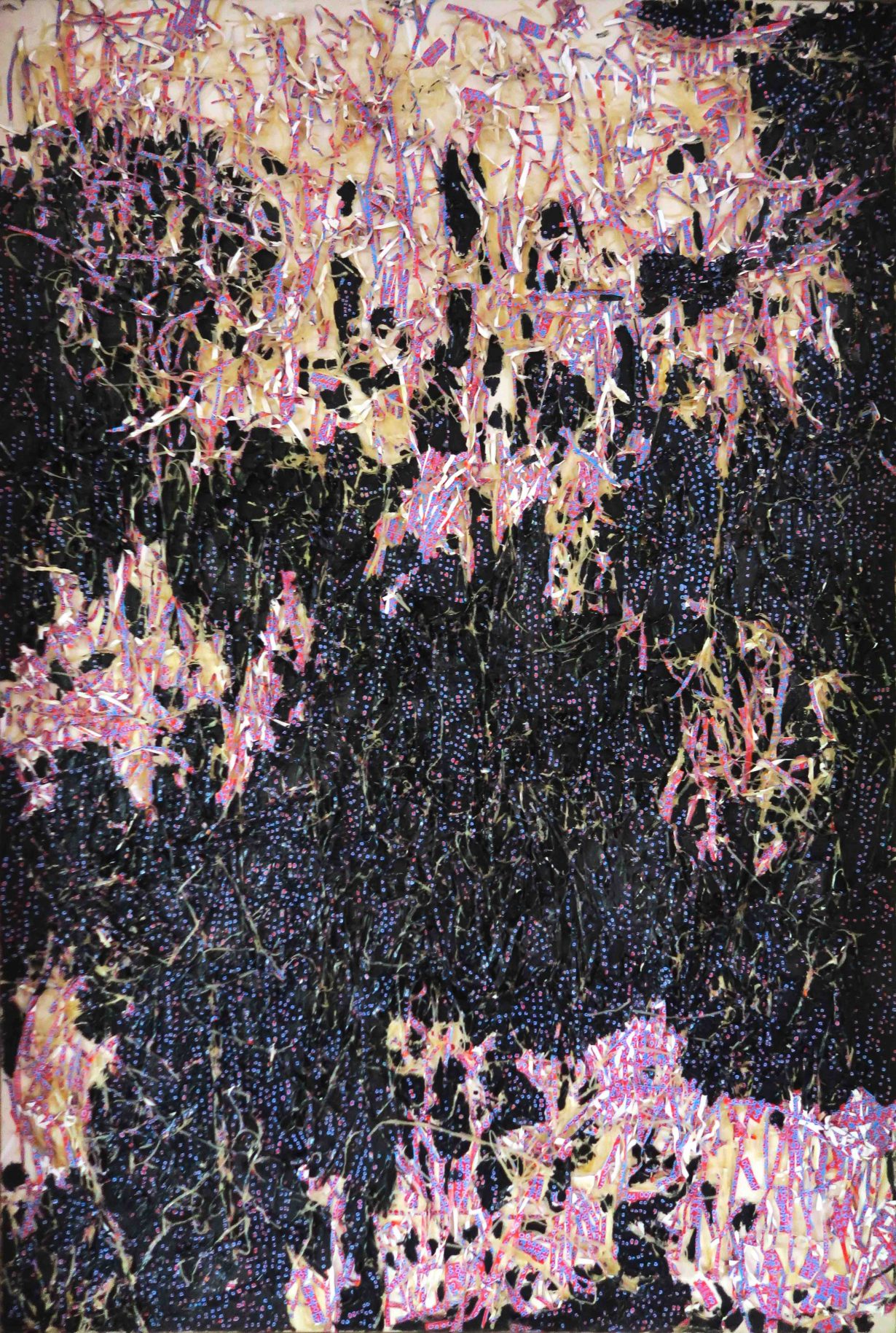

Udomsak Krisanamis: All is Prettier. Part III

100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, 7 October–19 November

Udomsak Krisanamis became known in the 1990s for his painted collages of printed matter, which he attached to canvas and covered with a mixture of paint, fabrics, cellophane sheets and noodles. The resulting works look like glitchy TV screens and Mondrian-esque grids of urban streets viewed from a satellite – he was indeed living in New York at this time. Krisanamis’s current three-part show at 100 Tonson Foundation, curated by Chomwan Weeraworawit, presents an immersive vision of what art means for the artist. Inspired by Andy Warhol’s words ‘all is pretty’ and his Factory – where he produced artworks en masse and hosted parties – Krisanamis covered the the Foundation’s interiors with silver foil and filled its space with painted car hoods, disassembled mannequins and other found objects (Part I: Speed), and works by his artist friends in Part II: Arrival. For Part III: Strike, there will be noodle collages like I Feel Fine (2000), as well as new works made this year like Looks Like Basquiat. Yuwen Jiang

Busan Sea Art Festival

Ilgwang Beach and other venues, 14 October–19 November

Busan’s Sea Art Festival started out during the build-up to the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. Held annual until 1995, it was subsequently incorporated into the better-known Busan Biennale whose organisation still runs the biennial event. The point of it, in case it wasn’t obvious is to place art in the context of the South Korean coastline and make that marine environment the centrepiece of the show, which, given the speed at which that environment is changing (from desiccated corals to rising sea levels and unpredictable typhoons and monsoons), the notion of the Sea Art Festival as a warm-up act has taken on a whole new depth of meaning, which would also make you think that such an event would be a little more prominent in the artworld imaginary than it currently is. This year’s edition, curated (following an open call) by digital-media and maker-culture expert Irini Papadimitriou, is titled Flickering Shores, Sea Imaginaries and aims at exploring the tidal pulls of exploitation and survival when it comes to humankind’s relation to the sea. The exhibition, centred around Ilgwang Beach, features work by artists such as Saudi Arabia’s Muhannad Shono and Busan-native Kim Doki, but for the main part a series of collectives and groups, such as the nomadic STUDIO 750. Presumably they’ll be urging us to wake up from the zombie-apocalypse that characterises our current relations to the sea, and, of course, Busan’s place in pop culture. Time for a sea change. Nirmala Devi

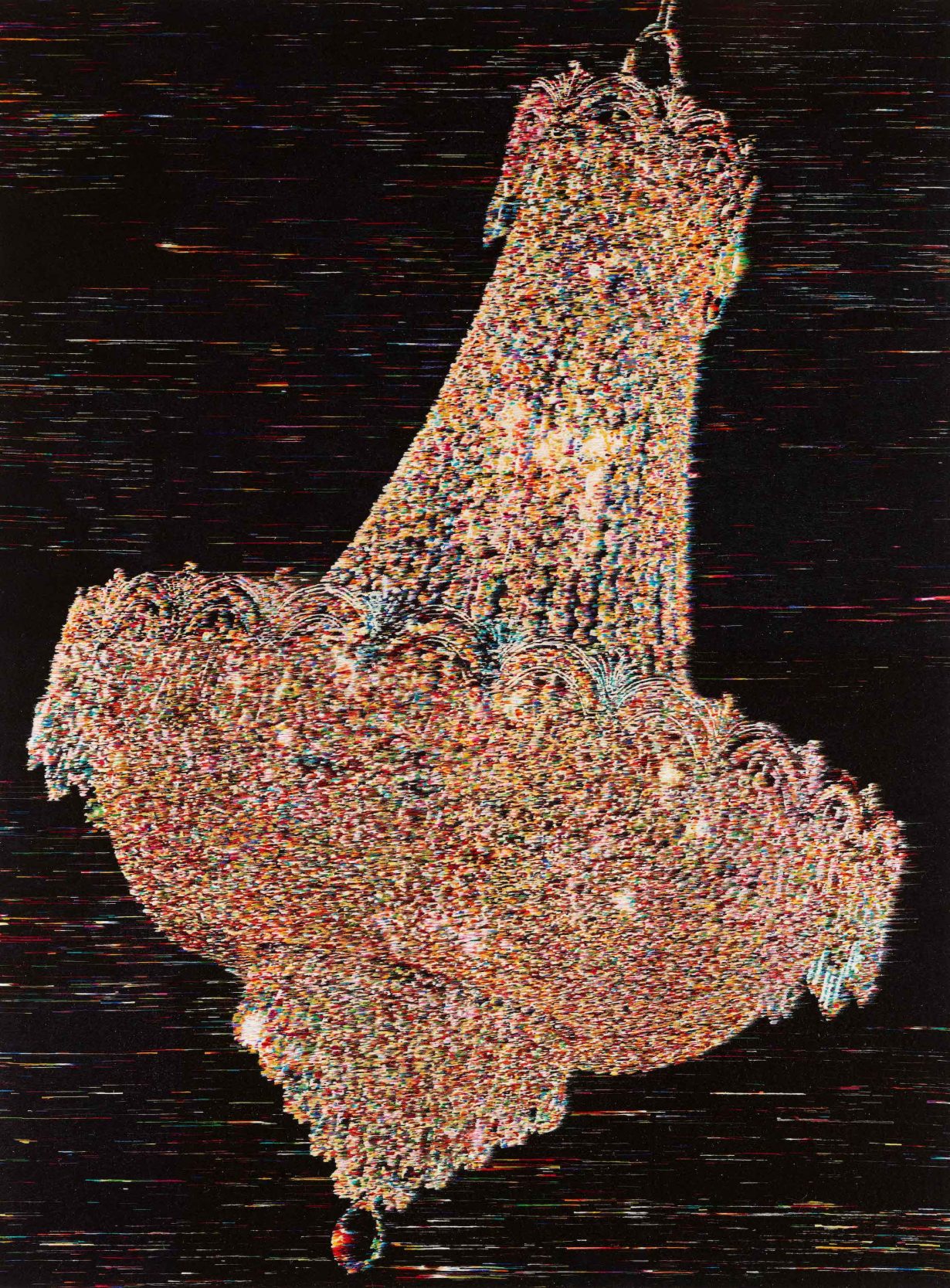

The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 21 October 2023–11 February 2024

The year 1989 was a pivotal one for much of the world – the fall of the Berlin Wall marked the closing chapters of the Cold War, revolutions in the Eastern European bloc pointed to the impending collapse of the Soviet Union and calls for democracy resounded worldwide. The Shape of Time: Korean Art 1989 focuses on these events’ impact on the peninsula, as told by 28 artists born between 1960 and 1986. Oh Jaewoo’s Let’s Do National Gymnastics! (2011), for example, evokes the standardised and almost militarised exercise routine executed in schools throughout Korea between the 1970s, 80s and 90s, emphasising the cultural pressure to conform, as well as the state’s ownership of its citizens’ bodies as part of its mandatory conscription policy. Kyungah Ham’s What you see is the unseen / Chandeliers for Five Cities (2016–17) is a bold series of hand-embroidered chandeliers that were a result of cross-border collaboration between the South Korean artists and artisans in North Korea. The effect is hauntingly beautiful, as it inevitably signals the material complexities of time and space. Marv Recinto

Indigenous Histories

MASP, São Paulo, 20 October 2023–25 February 2024

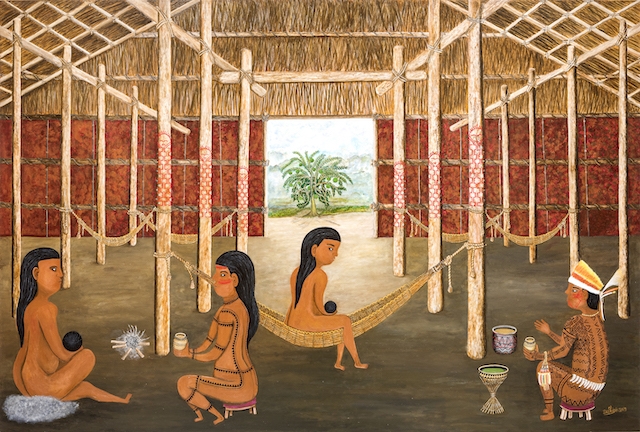

In Duhigó’s Nepũ Arquepũ, a 2019 acrylic-on-wood painting, a Tukano woman sits up in a hammock cradling a newborn baby. Nearby in the straw-roofed, mud-floored maloca the local shaman prepares the requisite blessings and medicine. All the trappings of the scene from Brazil’s remote northwest Amazon, for the western European eyes, are alien – the nudity, the bodypaint, the vernacular architecture – but the central subject is universal across time and place. Questions of material and cosmological commonality and difference loom large in Indigenous Histories, MASP’s centrepiece exhibition for the year (travelling to Bergen’s Kode Museum in 2024), featuring 285 works of around 170 artists from indigenous communities ranging the lands latterly named Brazil, Peru, Canada, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand and Norway. This is an ambitious project of Big History, encompassing questions of how life began, how it was lived and, for many of the communities whose work will be featured, how life has become precarious since the onset of colonialism. Oliver Basciano

Our Ecology: Toward a Planetary Living

Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 18 October 2023–31 March 2024

Comprising four ‘chapters’ of works by modern and contemporary artists in Japan and from around the world – including Ryoji Koie, Agnes Denes and Apichatpong Weerasethakul – Our Ecology: Toward a Planetary Living promises to encourage a concerted shift away from anthropocentrism, towards ecocentrism. Three of the four sections consider the Anthropocene more broadly, but ‘Chapter 2: Return to Earth – Art & Ecology in Japan, 1950s–1980s’ looks to the practices of Japanese artists during the postwar era. Since the seventeenth century, Japan’s economic exploitation of the environment has resulted in extensive devastation, including the Ashio Copper Mine disaster of 1907 and the ‘Big Four’ diseases caused by industrial waste and pollution. ‘Return to Earth’ features artists like Koie, Gaho Taniguchi and Natsuyuki Nakanishi, who engaged with these environmental calam- ities and criticised exploitative systems. At a time when ecological devastation poses an imminent threat, reckoning with the torrid past is an important part of looking to a more sustainable future. Marv Recinto

Ephraim Asili: Song For My Mother

Amant, NYC, 5 October 2023–28 January 2024

Filmmaker Ephraim Asili’s debut feature, The Inheritance (2020), which told the story of a Black Marxist collective in Philadelphia – a loose reenactment of Asili’s own young adulthood – gave the current exhibition at the Whitney Museum its title and subject. It reflected on the many meanings of the word inheritance, both celebratory and painful, and asked what lasts from an era, a person or an idea and how this might be passed on. At Amant, Asili is showing his newest film, Song for My Mother (2023), which considers the larger context that Asili is interested in, of thinking about Black radical collectivity, only from an ever more personal angle. Song for My Mother draws on the director’s family, specifically the story of his great uncle Dr. Richard Moore, who led Bethune Cookman University (BCU), one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and a designation of a network of higher education institutions started before the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964. Asili combines interviews and performances by members of the BCU community with archival materials and family photographs to shape a narrative that is incredibly personal but still makes an argument for collectivity. Orit Gat