The year in film: 2024 was the year the film industry could no longer ignore the real world, which it mines for content while denying any influence or complicity in its crimes

On 10 March 2024, Jonathan Glazer came to the stage to accept the Oscar for best international feature for his Holocaust drama The Zone of Interest. In his speech, he criticised the “hijack[ing]” of the memory of the Holocaust to justify Israel’s occupation of Palestine, “which has led to conflict for so many innocent people”. At the time, 30,878 people had been killed in Gaza. At the time of publishing this text, that number is 44,429.

In the intervening months, rather than heed Glazer’s condemnation, the film industry – as with industries across the world – has helped usher in a draconian culture of suppression, silence and financial complicity with the ongoing mass murder of Palestinians in Gaza. Glazer and outspoken pro-Palestine filmmakers have been denounced or blacklisted; protests at festivals have been ignored or quashed. No matter the empty gestures, vacuous acceptance speeches and backslapping of studio execs we are to be subjected to in the coming awards season, this – silence in the face of genocide – is the story of cinema in 2024.

No section of the film world is unstained. In Hollywood, the industry has been gripped by what an open letter to SAG-AFTRA called a ‘McCarthyist repression of members who acknowledge Palestinian suffering’. And on the festival circuit, there has been widespread dismissal of calls to cut ties with financiers linked to Israeli weapons manufacturers or illegal settlements. Mealy-mouthed appeals to ‘peaceful dialogue’ abound. ‘We do not take a position in geopolitical conflicts,’ said the CPH:DOX director – even though the festival explicitly expressed solidarity with Ukraine just two years prior.

Such gutless dithering reached its peak with this year’s Berlinale, which sought to have its cake and eat it too by awarding best documentary to Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham’s anti-occupation film No Other Land, then disavowing their ‘one-sided and activist statements’ after the directors criticised the ‘situation of apartheid’ under the occupation in their speech. Even more hypocritical was a subsequent letter from Berlinale bigwigs Carlo Chatrian and Mark Peranson, which spouted those familiar hollow truisms about ‘the power of cinema to unite’. What is the function of unity, one wonders, when one side wants an end to apartheid and the other side wants them to shut up?

Cinema ‘is neither right wing nor left wing’, Chatrian and Peranson stress, which is a little like saying cinema should have no politics whatsoever. This is an ideal of cinema in which no filmmaker should have ‘their political views scrutinised’, as Chatrian and Peranson say, so long as they engage in the polite impotence of ‘dialogue and exchange’. The reality of such noble fantasies of impartiality is, of course, stringent maintenance of the status quo. There was no dialogue with the Berlinale workers who demanded the festival call for a ceasefire; no dialogue with protesters at the European Film Market who had the police called on them. What ‘dialogue and exchange’ seems to mean is a lot of people nodding in solemn agreement about what a terrible situation there is in the Middle East, then doing nothing about it.

If there was a cinematic corollary to the Berlinale’s equivocations, it was Alex Garland’s Civil War, a 109-minute Call of Duty cutscene dressed up as a serious war drama. The film stages a fictitious conflict between an autocratic American government and secessionist guerrillas – but such distinctions quickly become irrelevant because Garland shows us nothing of the motivations of either army. He does, however, show plenty of contextless atrocities committed by both. And if all sides are as bad as each other, the only moral action is to take no side at all. In Garland’s worldview, no one could possibly possess a deeply held belief or want to make things better. Ideology, politics: none of it matters, only dog-eat-dog nihilism.

Garland has called the film a critique of ‘polarisation’, suggesting that ‘left and right are ideological arguments’, not a ‘moral issue’. I tried to imagine him making such a film about the actual American Civil War; would he also say that the issue was polarisation, and not that one side wanted to own slaves while the other didn’t? Such moral inertia is in fact the point of Civil War: to view any conflict as one extremism against another, in which case sitting on the fence is not cowardice, but a revolutionary act.

If Garland offered a reactionary approach to militant cinema, Coralie Fargeat did the same for satire. Fargeat’s The Substance presents itself as a critique of patriarchal beauty standards, following a middle-aged actress (Demi Moore) who takes a mysterious drug allowing her to live half her days as a younger version of herself. But the tools it uses to enact this critique – in particular, the genuine revulsion with which it regards the elderly form of Moore’s character – are indistinguishable from misogynistic hagsploitation films.

These images are intended to subvert this misogyny, of course, but it is difficult to register such intentions when they are so decontextualised as to have no bearing on the object of critique. Fargeat, like Garland, has spoken of her desire to distance her film from reality, setting it in a symbolic vision of Hollywood that is ‘timeless and thus universal’. The effect of such facile universalism is that, when we see a humiliated woman whom society invites us to view with disgust, that is what we see. What in the film, and the world, is there to tell us otherwise?

Even audiences seem unable to escape this detachment from reality. In my screening of The Substance, the sight of Moore’s gradual deterioration seemed to spark not empathy, but laughter. It was as if my company that evening were unable to connect what they were seeing to the real suffering of real women. Others laughed, too, in Sean Baker’s Anora, widely dubbed a latter-day screwball comedy. Yet this levity is mainly confined to the film’s bumbling henchmen. Its title character, fine wisecracker though she is, spends much of its runtime being belittled or abused. The audience seemed a little too eager to laugh at these moments, too.

No one has advocated against the real in cinema more than critics, however, among whom a mock-aestheticist ‘art for art’s sake’ attitude – dubbed the ‘aesthetic turn’ – is in resurgence. Art isn’t activism, they tell us, and aesthetic excellence is the only barometer by which we should measure art. This strikes me as an oddly oxymoronic notion: everyone from Sergei Eisenstein to Leni Riefenstahl could tell you that aesthetic form is a political question. (That Fredric Jameson, who championed the argument that aesthetic choices in fact had ideological underpinnings, should pass this year is perhaps a heavy metaphor Hollywood would approve of.) Nevertheless, in some quarters it has become fashionable to argue that art should stay in its ivory tower, lest it succumb to priggish sermonising.

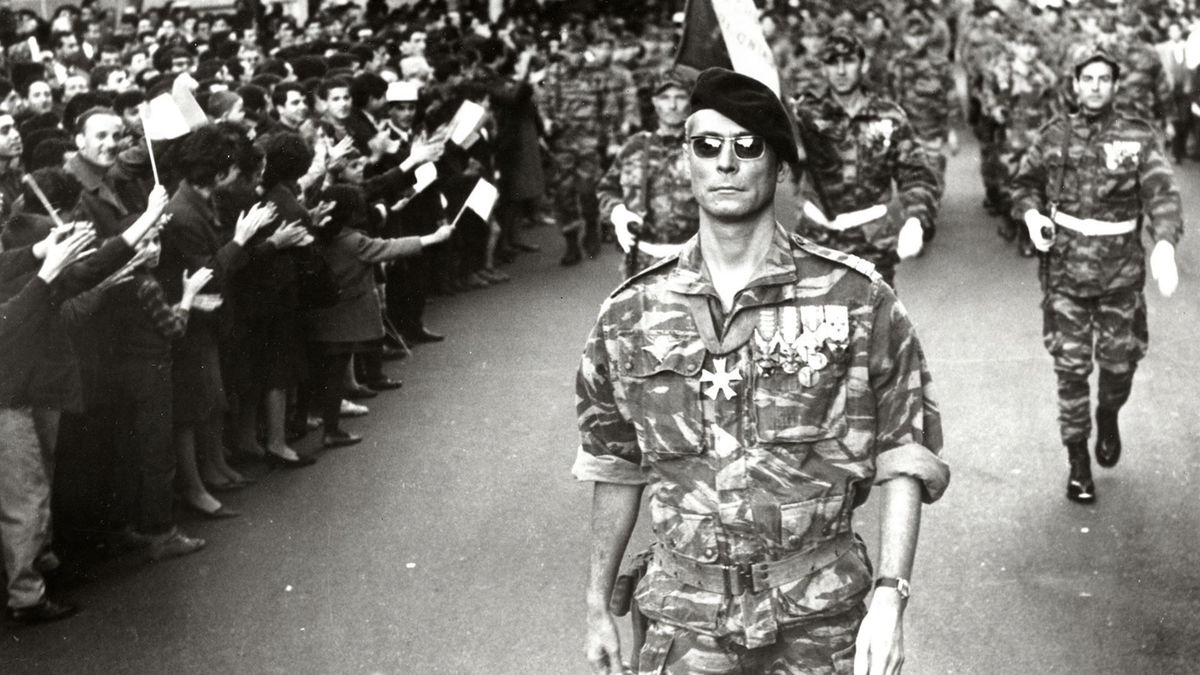

It’s undeniable that the Trump era has seen a rise in glib ‘lib’ moralising – I certainly have no desire to see another Don’t Look Up – but a view of cinema that believes it can have no activist function is as ahistorical as it is, well, antisocial. Godard, Ousmane Sembène, Heiny Srour: to ignore how politics shaped their aesthetic brilliance is pure folly; to ignore how they wielded aesthetics for political ends is pure misanthropy. Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) so shaped visions of insurgency that it was used for training purposes by the Black Panthers. Should we shut our eyes to such concerns because of stubborn insistence on aesthetic exceptionalism? An ‘art for art’s sake’ view claims to liberate art, but in fact diminishes it to an ineffectual, navelgazing parlour game. Ironically, it shares this effect of denying reality with the didactic art it claims to oppose: one pretends reality is irrelevant; the other pretends it can be fixed with Canva infographics.

Despite everything, there are still filmmakers who believe art might matter in the real world. The young people arguing about what anticolonial justice might look like in Mati Diop’s Dahomey, or the nurses throwing stones at property developer billboards in Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light; the filmmakers who withdrew their work from the Berlinale, from the NYFF and from IDFA to protest institutional complicity. To have such integrity comes with genuine risk: Maryam Tafakory, who pulled her project Sukhte-del from Berlinale Talents, chose to do so despite losing out on the funding she needed to complete it. Not everyone can be expected to make such sacrifices of livelihood and artistic expression. But it would serve us well to recognise the true stakes of the situation, and to remember that cinema can be more than a site of ponderous ‘dialogue and exchange’. It can also be a battleground.

Ian Wang is a writer living in London