The year in food: In 2023, tastemakers stuck to known quantities

Walking through Narrow Way Square in Hackney Central, East London means walking to, past or by three majestic Caribbean fruits. Veronica Ryan’s Custard Apple (Annonaceae), white marble petals softly tessellating; Breadfruit (Moraceae), its skin taut and robust; and Soursop (Annonaceae) (all 2021), invitingly spiky and soft green, form the first public monument in London to the Windrush generation, and the shameful scandal of their detention and deportation. The sculptures sit in dialogue with the fruit markets that inspired the monument. This was Ryan’s intention: for the work to not only bear witness, but also become part of the public space, for people to touch, sit on and use as much as to admire and contemplate.

This year, one of London food’s new tastemakers took his chance to engage with Ryan’s monument. Jesse Burgess, the thirty-two-year-old frontman of influencer outfit Topjaw, sat down on Ryan’s soursop to film a YouTube video on the best pubs in East London. These guides to pubs and restaurants are the core of Topjaw’s output, along with man-on-the-street interviews, in which they ask famous London chefs and restaurateurs about their favourite restaurants, bars, bakeries and cafes, as well as the places they feel are overrated and underrated. Burgess, introducing the video to an audience of hundreds of thousands, gave a jocular nod to a mate, a character from previous episodes. “We miss you Pickle… So much that we sat on one.”

This small and ill-judged thoughtlessness sticks with me when looking back on 2023 in food, not for its magnitude but for its simplicity. Regardless of the size and renown of the place you are acting as a guide to, which for the purpose of this essay is London, it is not that difficult to be aware of something you are sitting on, but I suppose it’s easier still to not have to think about it at all. Not every person who has walked through Hackney Central since the monument was inaugurated needs to know on sight that they are looking at a breadfruit, soursop and custard apple, but I think it is important that someone whose persona, reputation and, ultimately, livelihood (partly; Burgess is a former model and current property developer, a natural pathway into culinary expertise) rest on understanding the fabric of London food at least has a clue about the city and its context. More important still is that he – and anyone else seeking to direct people’s tastes – recognises that there are myriad people who will immediately know that they are looking at breadfruit, soursop and custard apple.

Later in 2023, another chef who has risen to prominence (and then opened a restaurant) via TikTok, Thomas Straker, drew criticism for an Instagram caption reading ‘kitchen team assemble’ below a photo of a brigade of exclusively white male chefs. His restaurant, Straker’s, is on Golborne Road in Notting Hill, a crucible of Black British history in London. His riposte to the criticism, in a later interview with the Evening Standard, involved comparing his team’s demographics to the Moroccan butcher’s shops in the area, who employ Moroccan butchers behind the counter. Prior to those comments, the same paper gave his restaurant 4/5 stars and lauded how he had ‘possibly cracked the code of aspirational deliciousness for a new generation’.

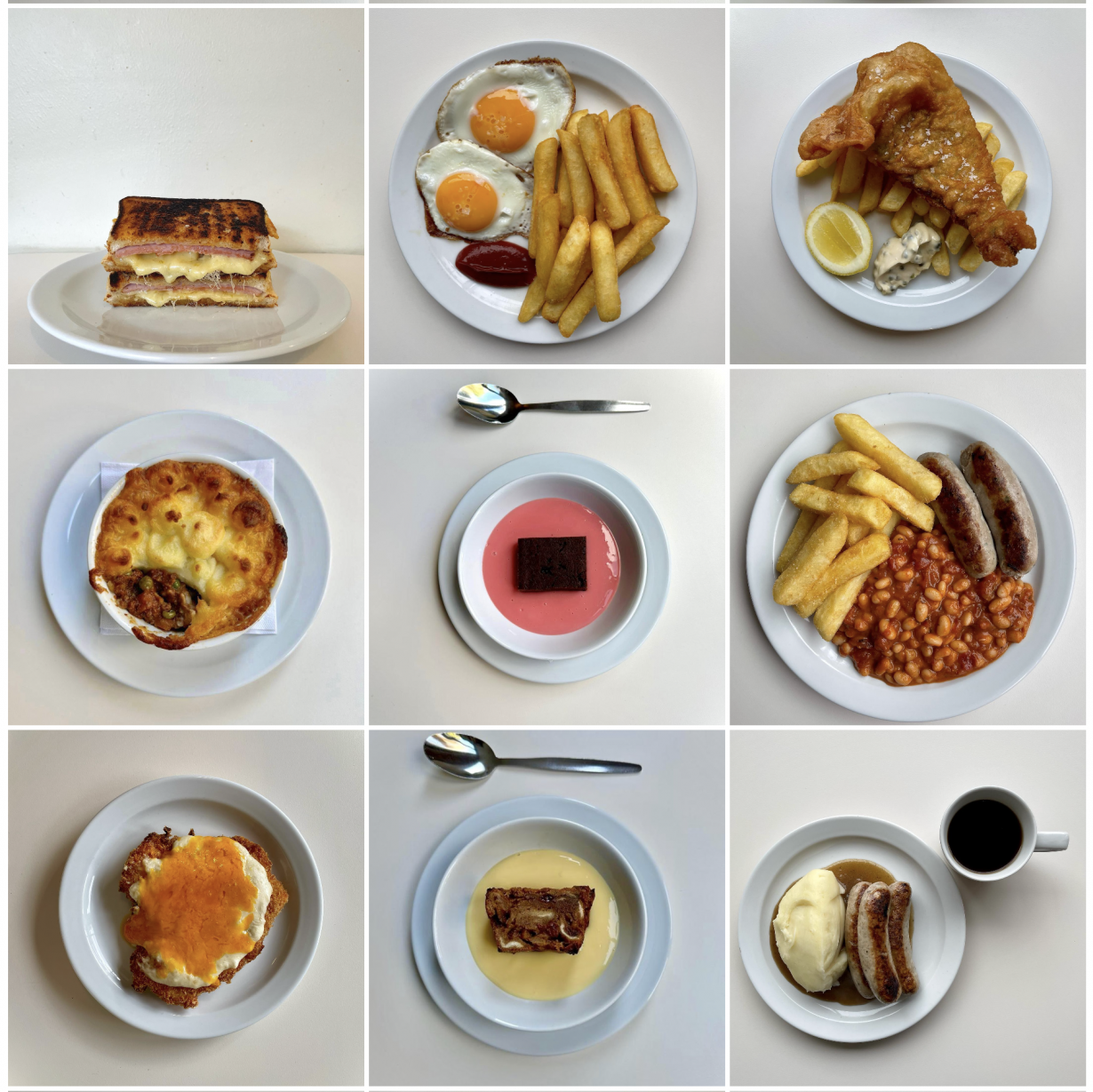

It’s this ‘aspirational deliciousness’ that new influencers like Burgess and new restaurateurs like Straker seek – and given their subscriber numbers and waiting lists for reservations, it’s clear that plenty of people seek this too. It’s there in the austere nostalgia of Norman’s, the yassified greasy spoon in Tufnell Park that now counts Burberry as a collaborator; it’s there in the chicken beak poking out of a pie at Fowl, the spin-off of another TikTok hit, Fallow; it’s there in rampant demand to eat a £15 brisket sandwich with another full-time property consultant, part-time tastemaker, Eating With Tod; it’s there in what Esquire heralded as ‘the return of normal food’, where foodies are a punchline, the chefs behind three-Michelin-starred restaurants are legends for loving Cathedral City cheddar, and ‘normal food’ is delineated as Stella, Coca Cola and sliced white bread, the working class heroes of globalisation.

What emerges is a no-place aesthetic of London cuisine, that purposely blurs and blends referents of place, time and memory until they lose their bearings. Whether engaging in poptimist pyrotechnics by putting pickled onion Monster Munch on oysters, or once again going to the well of stone fruit with burrata, it has no specificity beyond the brand of the chef or restaurant who cooked it. This complete desensitisation of context even impacts emergent tastemakers that purport to be all about specificity of place. Real Housewives of Clapton and Socks House Meeting lean into granularity when parsing the olive habits of E5 residents or assessing which pocket of Hackney a litty lengy gorly’s coffee will come from. But in satirising such a small but powerful demographic, while making money on collabs with the brands they mock, present a flatter version of the city than the screens on which they exist.

It’s important to say that there are great restaurants in this city that work in this mode of blurring and blending, but their practice is more like a refraction. Be it a family-owned Thai restaurant in East London (Leytonstone’s Singburi), West African in fancy West (Fitzrovia’s Chishuru), makhani chicken buns and soft serve swirls in Stoke Newington (Bake Street), or Bermondsey’s old favourite 40 Maltby Street, they keep their specificity; they speak in a vernacular. They are living products of their context, where no-place cuisine and the tastemaking that drives it yearn for the vacuum, where whether or not it’s 2023 wouldn’t matter at all. The unifying force behind this homogeneity is not the incuriousness of its figureheads, nor the deadening forces of urban development, and capital, and algorithms – although they are partly to blame. Rather, it is a different and more deadly kind of incuriousness: the kind that cynically takes root in apathy towards the political realities of these forces and of food, that assumes its audience – and even its subjects – won’t notice or care that they are being aestheticised out of view.

If some of this seems old, that’s because it is; 2023 in food has reminded me that, in Britain, largely, the place of food and restaurants in the popular psyche exists in a perpetual 2016. Byron, which that year collaborated with the Home Office on an immigration raid, passed itself round in a game of private equity pass the parcel, again, and lost, again, closing restaurants and going into administration. The discursive afterglow of Brexit – coupled with the main outlier from this perpetual 2016, the impact of COVID-19 – remains a sunlit upland, despite the ensuing rising costs, paperwork and pressure on staffing forcing a nearly 50 percent increase in restaurant closures. And still, Masterchef suggests that the pinnacle of dining is a prime cut of meat cooked fast, a cheap cut of the same meat cooked slowly, a vegetable manipulated three different ways, a reduced French sauce, and a chocolate fondant with a devastatingly solid middle that host Gregg Wallace will sink his many sweet teeth into. Staples of European, Southeast Asian, and South American cooking like polenta, lentils and quinoa are still ‘middle-class’, because the British working class can only ever be white and subsist on chips and cigarettes. A beautiful, new Serpentine Pavilion dedicated to the connective power of food houses chain cafe Benugo.

To round off the year, Jamie Oliver is opening a new restaurant in the heart of Theatreland. It’s unlikely to slap on TikTok. After his Jamie’s Italian empire collapsed in early 2019, owing hundreds of thousands of pounds to creditors and staff, some of whom had to go to employment tribunals, his cookbooks and TV brand kept him afloat. Now he’s back on a piece of prime real estate in central London, bolstered by sympathetic profiles and invite previews, selling a menu of Chat GPT British-European comfort food peppered with chic 2023 signifiers to maintain relevance (day-boat fish; Flourish [a farm beloved by top restaurants] salad). There’s a Kashmiri-spiced tofu skewer paired with Levantine smoked aubergine and North African harissa. And then there are the Jamie Oliverisms: buttery mash; rich tomato bisque; and, below the scampi: outrageous pickle ketchup. Perhaps he’s been to Hackney Central.

James Hansen is a culture writer and editor based in London. The former deputy editor of Eater London, his work has recently appeared in The Drift, Dirt, Vittles and Bon Appétit