Was China’s community of Self-Comb Sisters a radical act of feminism?

Featuring mostly Asian artists, Threads of Kinship weaves a tangled web of colonial commerce, migration, utopianism and female resistance. These grand themes unspool across the region like long geo-economic strands from a conceptual chrysalis: a sisterhood that emerged from the nineteenth-century silk industry in the Pearl River Delta in southern China. The exhibit’s curatorial thesis centres on sericulturists and weavers who were among the first women in China to work together in large numbers and earn a good wage. Camaraderie and financial independence were their tickets out of marriage. The women organised themselves into female phalansteries. They took vows of celibacy, calling themselves Self-Comb Sisters because initiates had their hair put up by fellow members, pointedly deviating from the tradition of mothers and sisters pinning up the bride’s hair in preparation for conjugal life. During the 1930s the silk business collapsed, and many of these gupo, meaning ‘older unmarried aunt’, moved to British colonial Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong as domestic workers. There they set up sisterhood houses and sent money back to their families every week.

One reading of ‘sisters doing it for themselves’ is that it turned the old order upside-down. The curators make a literal point of this with Hu Yinping’s Potatoes Grow on Trees (2025), woollen potato plants hung from the ceiling, nourished by air not soil. Crocheted by a collective of older women Hu set up in her hometown of Luzhou in Sichuan Province, the potatoes have the cooperative roots of the Self-Comb societies.

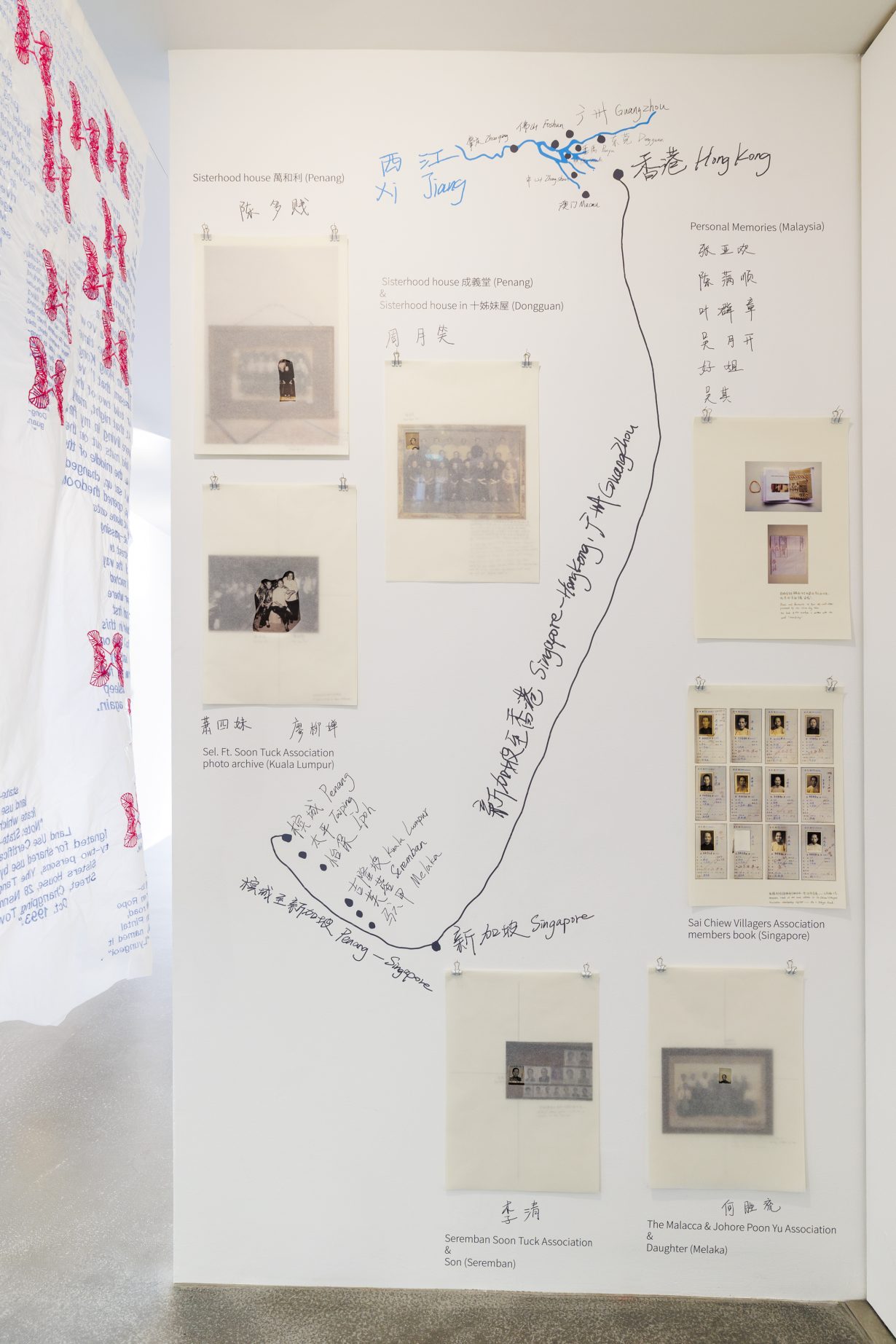

Of the 11 artists in the show, Chen Jialu is the only one to work directly on the Self-Comb women. She has pieced together their lives out of interviews and the scant archival material she could track down. In Gupoyu (2022), excerpts of testimonies about the gupo migrant experience are embroidered on dissolvable white fabric. Red leaf motifs obscure words here and there, making the powder-blue texts hard to make out. Their meaning is as fragmented as the Self-Combed life, lived neither wholly here nor there, radical, marginal and diasporic. In Hear (2025), interviewees cheerfully reminisce about the hard old days, their recorded conversation emanating from a suspended coil of braided hair. As always, hair purveys multiple feminist meanings. In Ashmina Ranjit’s Hair Warp (2020), a swirling abstract of charcoal and pastel curls rebels against the neat coifs of Hindu wives. In Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann’s digital photocollage Like the Banana Tree at the Gate: A Leaf in the Storm (2016), hair wields fear. Curtained in long hanging hair, the women channel the pontianak, the male-eviscerating lady spirit of Southeast Asian lore.

Women’s garments are something to fear, too, in Sawangwongse Yawnghwe’s clothesline installation, Yawnghwe Office in Exile (2021). After the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, Burmese women hung up laundry lines to fend off superstitious soldiers, afraid the clothes would steal their virility. Gaëlle Choisne’s cape is invested with a superpower of another kind, shamanistic and protective. Hung on rusted rebar, the satin is studded with debris that littered the route Choisne’s mother travelled from Haiti to Brittany in France. Choisne’s Entre chien et loup (2015) is an Afrofuturist turn on the exhibit’s Asian story of immigration and trade. A map of the region’s silk-trade routes printed on Risham Syed’s mother’s silk quilt, Ali Trade Center Series iv (with Buddleia) (2022), evokes the colonial trade that gave rise to the Self Comb system.

Birthed by capitalism, does this autonomous, transnational community of women fit into that other Western ideology, feminism? The sexual liberty of Ma Qiusha’s fishnet stockings in her mosaic Wonderland-Eros No. 3 (2020) and Ranjit’s and Yee’s hair portraits say yes, but they are an inaccurate translation of Self-Comb empowerment. Many women joined the order for reasons that had to do with pre-serving the patriarchal hierarchy, not supplanting it. Economically independent, the sisters were, nonetheless, feminists of a peculiarly Confucian kind.

Threads of Kinship at Kadist, Paris, through 10 January 2026

Read next Hito Steyerl’s ‘Conservative’ Turn