For decades, the artist has made paintings that, for all their productive anachronism, feel both astral and intimate

When I was young, the thought that my mother might die terrified me. Back then, before I had understood that dying is not optional, my mother would tell me that, were it ever to happen, I shouldn’t worry because she wouldn’t disappear; she would just become very tiny, and I could then carry her around in my pocket. She would become something else. Over time, I learned that ‘becoming something else’ happens very rarely in life but quite frequently in art. In Victor Man’s art, it happens a lot: to both people and things.

An artist of vivid, nocturnal imagination, for the past two decades the Romanian-born, Cluj- and Rome-based artist has made paintings that feel both astral and intimate. His subjects often revolve around a few familiar figures, subjects of his affections: his repertoire is concise, often auraed with domesticity, yet sometimes crossed by presences with which we have mostly lost affinity, such as archangels of the type seen in altarpieces or symbolic characters from archaic legends. Intimacy also informs the scale of his canvases, which often invite viewers to lean in and peer closely: Man’s art is not one of magnitude but of a whispering proximity. His palette, too, is pointedly minor-key: livid and pensive, flickering in what otherwise seems to be a perpetual twilight, lit up at times by sudden phosphorescences. Here, things lie very close to each other, memory is tangible and proximal; sleep and wakefulness interweave; death accompanies the living.

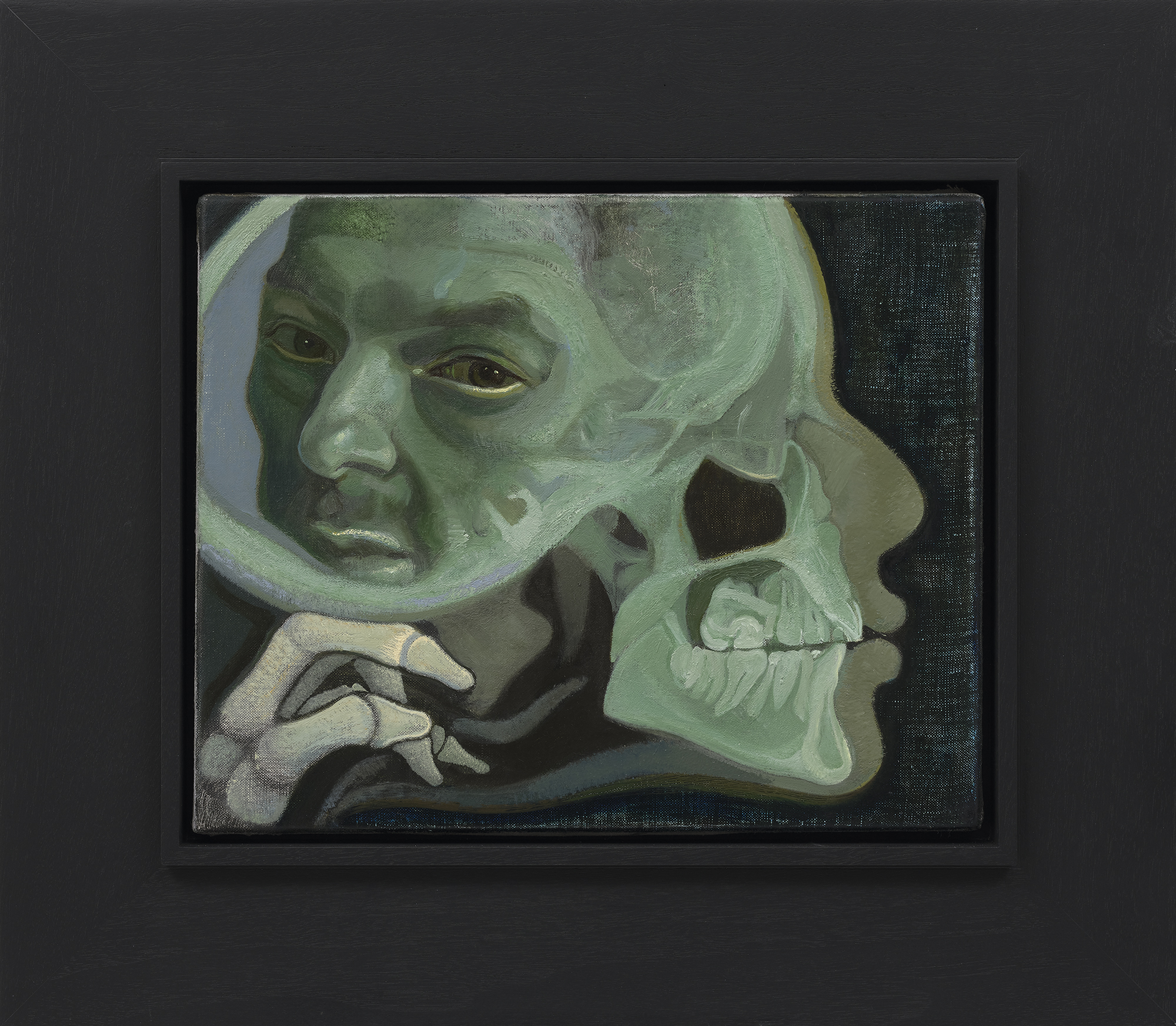

In Umbra Vitae (2025), for example, the artist’s self-portrait dwells, like a thought, inside a side-on X-ray of his beloved’s skull. A skeleton hand appears below Man’s chin, like that of a contemplative thinker. Bathed in a cold, leaden light, this three-way conversation spans time: it convenes, in one place, those who look to the future, those who contemplate the past, and those who come from there. In this work’s concise, emblem-like visual economy, the classic psychological theme of the self-portrait emerges within a diagnostic framework, intermingling the enduring iconography of mental introspection and the clinical iconography of medical examination. Inside the almost epidermal contact between self-portrait, X-ray profile and the hand’s bones, a feeling of contiguity arises between existence and whatever ‘something else’ awaits it. If we might say that death is cast over life like a shadow, Man here confronts us with a different regime of continuity, one of mutual pollination between being and disappearing, as if the connection between the two was a matter of touch, a space of tenderness.

A similar dynamic of osmosis pervades a subject to which Man has returned frequently in recent years: motherhood. The emeraldine flesh of mother and infant in Maternity with Legend (2024) seems far from life as we know it, yet its unnatural and alien appearance takes nothing away from the profound intimacy of this image, which is sentimental despite that aforesaid radical distance. As often in Man’s painting, the subjects are captured in a moment of silent stasis, a state of metaphysical inaction that signals detachment from our present time. This stillness places them in a remote space that’s nevertheless dense with the ghostly history of Western painting, that repository of motifs with which the artist has long engaged. If Umbra Vitae seems to engage in a conversation with the memento mori format, in Maternity with Legend one might note a relationship between the gaze of the mother – turned elsewhere, almost unseeing – and the motif, recurrent in Christian painting, of the melancholic gaze of the Madonna, whose sadness signifies her being aware of Christ’s future suffering.

In Man’s cosmology, then, death is not limited to the dimension of a single tragic event but rather understood as a constant presence that expands throughout life, impregnating it like an atmosphere or a mood. The mother and baby – the latter almost statue-like in slumber – face a sort of shelf on which a small, golden, male figure appears. Naked, he crawls on all fours, and from his head thin rays like glowing filaments radiate, suggesting his saintly nature. Everything here evokes an atmosphere of penitence, and the ‘legend’ mentioned in the title leads us back to ancient times, when stories were handed down even if uncertain; to a time of faith, when concepts of truth and plausibility were a far cry from those of the modern day.

Today, certain stories are still needed, at least sometimes. Death must be made understandable to children, often by inventing tales, by placing expiry against a metaphorical horizon that embraces metamorphosis and apparition. A horizon of consolation in which something might become ‘something else’. In attempts to explain death to children, some describe it simply as nonbeing; others feel the need to imagine our existence beyond its pure biological matter: an existence of symbols, a life reinvented like everyday objects are when deployed in games. Art, since time immemorial, has intermittently taken on this regime of symbolic transfiguration. At different stages of the history of Western painting, some of its exponents felt the need to articulate a distance from their own present, revisiting those moments in figurative history when the sacred was manifested in everyday life, and the supernatural was not quite distinct from the prosaic.

When Émile Bernard or Paul Gauguin, for example, revived echoes of medieval sensibility in their paintings, they created a space of visual anachronism that, for artists such as Man, is still deeply fertile today. It involves a sense of distance from one’s own time, a perception of the contemporary environment as inhospitable, the need to find refuge in images produced by those artists who, in the past, felt a similar loneliness in their own present. When, in Self with Saint Michael the Archangel (2024), Man portrays himself with palette in hand and what appears to be a small reproduction of a painting behind him, he reactivates an artistic mythology that a certain modernity and the whole of postmodernity have long been committed to deconstructing, that of the artist at work, alone, the tools of art in their hands and history at their back. With its provocatively romantic character, this image reveals conflict, perhaps exile; certainly a desire to summon something now distant yet vital, and that ruminates deep inside the fabric of art history even when seemingly dormant – namely the relationship between artistic individuality and the history of imagery, between interiority and the repertoire of forms that have accumulated over the centuries.

If that title, Self with Saint Michael the Archangel, helps us identify the figure behind Man, on the palette there are two beasts clashing, a reference to the iconography of victory over evil that has taken the form of a dragon. Man scatters these references; he unearths them and reworks their symbolic provenance and enigmatic nature, making them malleable; he draws from different forms of artistic and historical knowledge and returns us, it feels, to a secret. Although interwoven with references, his work resists any linear, erudite iconographic examination, just as it resists our present culture, so often made up of assertive, over-enunciated meanings. Of course, these paintings may also be viewed without the interpretative apparatus that decodes the accumulation of signs. What they preserve – and this is something very fragile, although capable of surviving the centuries – is the potential for an image to remain mysterious, to exude humanity despite appearing removed from time, and feel palpable despite receding into the distance. And concerning the relationship they suggest between humanity, proximity and distance, they speak, in ways variously sidelong and direct, to the present day. For almost two years, death has been flowing through my phone, our phones, without metaphor. It is always disjointed and chaotic, with no silence nor making whole. For months, the extermination of Palestinians in Gaza has repeatedly reaffirmed the reality of death, without it ever becoming ‘something else’, as it had when my mother helped me ward off those thoughts of the end. In Pietas (Flower of Gaza) (2025), Man uses a colour scheme typical of his work: a blue-grey complexion, unknowable-feeling and distant. It is rarely clear in his paintings whether this tonality is the result of the figures’ immersion in a symbolic atmosphere, their familiarity with death or their exposure to a shadowy and lunar light. In Pietäs, though, which features the profile of a clearly deceased man, eyes half-closed, this colour scheme becomes terribly real and leaves no room for doubt. In many of his works, Man gives his subjects half closed or divergent eyes, as if scrutinising an enigma and themselves an enigma. These ones, though, are the half-closed eyes of someone who has left this life and not yet found burial. And it is burial – together with the love it brings with it – that is evoked here, not only through the shroud framing this face but also, and above all, through the face of a woman caressing his forehead.

This skin-to-skin contact between the living and the dead is what gives the painting the gravitas of a lamentation, its compositional structure and emotional temperature. By echoing the Pietà, this painting confronts us with a possibility, which is also a space for compassion: the possibility for an iconography that has crossed centuries and borders to mutate throughout time, yet maintaining intact, in the present, a sense of identification with the pain of others. While in his self-portraits Man reactivates a device that, historically, has always provided a space for introspection as much as for dialogue with the past, with a work such as Pietas (Flower of Gaza) he evokes something that is human before being speculative and artistic: the condition of the witness, of those who see and know what happens in their own time. Once again, he seems to connect with a tradition that offers him a background for understanding the world, this time going back to moments in the history of Western painting when artists referenced the atrocities of their own present, like Francisco Goya did with his Napoleonic war painting The Third of May 1808 (1814). Here, Man offers a modestly scaled, beckoning memorial, a compressed funerary monument vibrating with lamentation. It’s a meditation on what it means to see through the prism of the past, and what it takes to feel in the present.

An exhibition of Victor Man’s work is on show at David Zwirner, London from 18 September to 31 October

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.