Art is not Rest at Muzeum Susch, Switzerland recovers the late Czełkowska as an ever-contrarian yet dedicated political artist

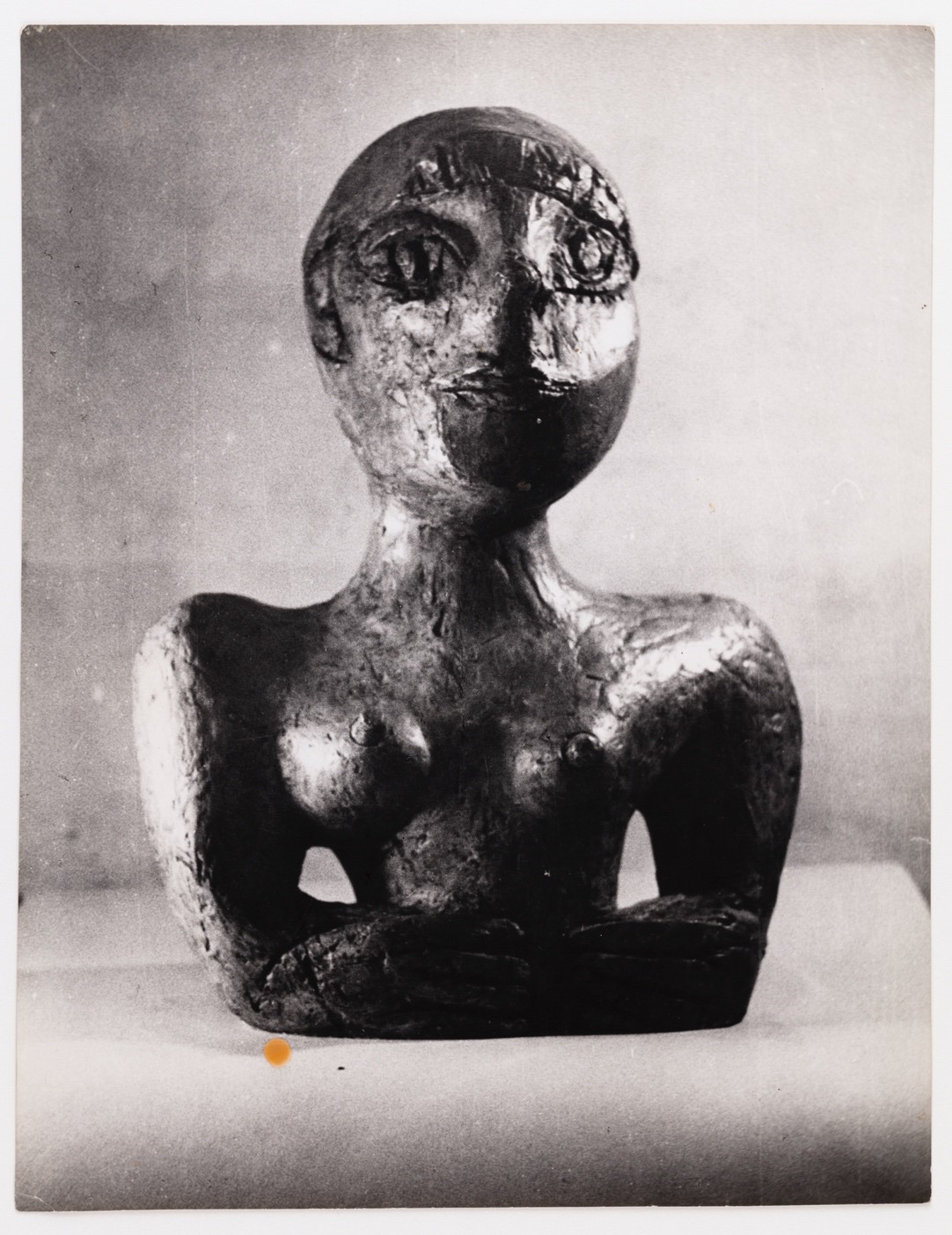

At Muzeum Susch, an exquisitely designed, women-centric private art museum, Wanda Czełkowska’s bronze Autoportret (Self-Portrait, 1959) occupies a topmost room, facing a window framing the idyllic Alpine landscape. Little could be further from the former Warsaw lorry depot where the Polish artist worked prior to her death in 2021, forever a contrarian who doubted art’s political efficacy, yet one whose dedication to artmaking was arguably more political than most, determining a life that transcended many societal constructs. The nude bust both conveys the influence of Minoan art and exudes the aesthetics of Eastern Bloc Expressionism abstracting away from Socialist Realism. It’s less formally daring than the mangled, hole-ridden genderless forms of her extraordinary 1970s Heads elsewhere in the show. But the erect mien – wide eyes, equally staring breasts/nipples, primitive hands flattened across torso – demonstrates the dualism of irony and intentness that a woman and modernist in Poland must then have felt, and which reverberates today. That it’s recognisably her is echoed in the striking photograph Temat (Theme, c. 1970), which pursues the head as a concept – ‘Arms and legs don’t matter to me,’ she wrote in her notes, ‘it’s all about the head, what’s inside’ – while showing the artist apparently suffocating herself in muslin, those same perspicacious eyes wide behind the gauze.

Czełkowska’s evolution is also apparent in a maquette of the seated stocky figures of Gracze (Players, 1960–61) – never realised as public art despite winning a commission for that purpose – which cameoed in Andrzej Wajda’s film Man of Marble (1977), about a journalist in search of the man behind the eponymous effigy of a Stalinist-era worker. In a scene filmed in Warsaw’s National Museum, Gracze can be seen on display, its egalitarian, leisurely locus (the artist left a space for the viewer to sit with the lifesize figures at their bench) a clear departure from earlier dictates. Unsurprisingly, 14 years after she joined the Polish avant-garde’s famed ‘Second Kraków Group’ in 1968, Czełkowska quit, apparently uneasy with members’ apathy to the paranoid restrictions of the Polish People’s Republic after it imposed martial law during the early 1980s. Interviewed by the visionary promoter of Eastern European art Richard Demarco, who showed her at the Edinburgh Festival in 1972, she said, ‘I am not impatient to wait for favourable conditions. The only thing that matters is the conception, and that it will be realised one day.’

In this first solo exhibition outside Poland, the venue’s architecture and the sympathetic curating of Matylda Taszycka, who expertly navigates the issue of neglected female artists and the Polish context in the catalogue, provide those ‘favourable conditions’. Here is Czelkowska’s largescale steel Stół (Table, 1970), 18 plaster casts of one head populating its chequerboard of metal squares, pitching the viewer into associative spirals. A windowless space, meanwhile, offers an ideal home to Bezwzględne wyeliminowanie rzeźby jako pojęcia kształtu (Absolute Elimination of Sculpture as a Norion of Shape, 1972/95/2023). On the floor, a grid of 66 prefabricated concrete squares; above, 66 lightbulbs installed in linen coffers provide a mirror-constellation of sorts, tremulously delineating the void. Experiencing Czełkowska’s work in this setting of literal and affective ‘neutrality, I wonder about the placement of her Autoportret, gazing towards the mountains in the canton of Graubünden, coincidentally where Nietzsche spent his summers. She is, it appears, looking inward as much as looking out; and, as per the show’s title, never at rest.

Art is not Rest at Muzeum Susch, Switzerland, through 26 November