In a series of exhibitions and performances from across the Pacific, Neha Kale finds a shared historical struggle

Wansolwara, a pidgin word from the Solomon Islands that loosely translates as ‘one ocean, one people’, is an ambitious exhibition that spans two institutions and features work by 20 contemporary artists with ties to Oceania and the Pacific. But Wansolwara rejects the ideas of geographical categories defined by generations of colonial explorers – and now the cavalcade of tourists, wearing plastic leis, that tumble daily off hulking cruise ships. Instead, it revolves around the idea of a single continuous waterscape that knits distinct communities in a shared kinship. In doing so, in the context of a year that marks the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s voyage to Australia, it refuses the terms of modern-day geopolitics – and imagines, in its wake, a different kind of future.

A woman lies facedown, arms outstretched, back illuminated by a chandelier. She adjusts her body slightly, as if trying to make herself more comfortable. She turns her head, locks eyes with the viewer. Around her, palm fronds glisten, quivering with secret energy. This scene is charged, alive with hidden meanings. But you are left in the dark.

Dark Light (2017), a videowork by Samoan artist Angela Tiatia, hangs in the front room of Sydney’s UNSW Galleries. The work refers to a famous image: Max Dupain’s Sunbaker, a 1937 portrayal of suntanned leisure that’s come to stand in for all the breezy freedoms of Anglo- Australian life. But in the presence of the more recent work, I am reminded of something else – Paul Gauguin’s 1892 portrayal of his young Tahitian mistress: Spirit of the Dead Watching (Manao Tupapau). His subject lies flat on her stomach, hand concealing her face, presenting Oceania as sensual and mysterious, an extension of the artist’s basest desires. Tiatia’s work, too, is sensual and mysterious. But the mysteries are those that arise from wrestling with your own subjectivity, of acknowledging how you’ve been shaped by who is watching you and summoning the courage to watch back.

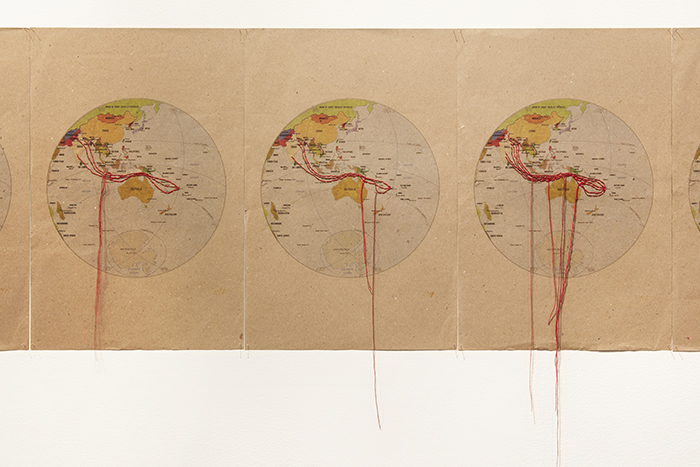

On the first floor, a minisurvey of work by twice-removed Fijian-Indian Australian artist Shivanjani Lal centres around Yaad Karo (1879–1920) (2019). Across this series of maps, lifted from a 1980s school atlas, the artist hand-stitches the route free ships once took across the Pacific. Alongside this, she sews the path taken by her ancestors, part of the Girmitiya, the community of Indians who, under British rule, were transported to Fiji to work on sugar-cane plantations as indentured labour (thus replacing outlawed slave labour, allowing Fijians to preserve their culture, and ensuring revenue for European settlers).

In Hindu culture, crossing the ocean – the kala pani, or black waters – was taboo, dissolving links to caste and kinship. Lal’s stitches, done in red thread, the threads often loose and fraying, grow increasingly assertive. At some points, the maps, which centre around Australia, itself complicit in the same colonial systems, appear to drip with blood. To stitch is an act of repair. But it can also suture. And to heal a wound, you have to acknowledge it first.

Slavery, of course, occurred across the British Empire, everywhere from British Ceylon to Jamaica and Barbados. So many former British colonies, scattered throughout the Great Ocean, are still grappling with the legacy today. The idea ‘one ocean, one people’ doesn’t just refer to the past or the future. It also recalls a shared sense of historical struggle. Although Wansolwara highlights these specific tensions, it leaves the viewer to do the work of finding resonances between different post-colonial realities. And given the buried nature of many of these narratives, this feels a little like a missed opportunity.

A centrepiece of Wansolwara is ‘O le ūa na fua mai Manu‘a’, a series of moving-image works curated by Léuli Eshrāghi, a Montreal and Darwin-based Sāmoan curator with Persian ancestry. Taking its title from a Sāmoan proverb that references the relief that greets long-awaited rain, this part of the show debunks Western modes of seeing and knowing. For instance, the 2016 videowork Creatura Dada, by the Anishinaabe French artist Caroline Monnet, inserts native female artists into Dadaism’s origin story. But the magic, for me, was about seeing First Nations women – such as director Alanis Obomsawin and artist Nadia Myre – devour grapes, slurp oysters and impale lobsters, lost in the realm of the sensorial, seizing the pleasure that Dali and Duchamp took for granted. Elsewhere, Bundjulung and Ngāpuhi choreographer Amrita Hepi’s A Body of Work (At the End of the Earth) (2017), in which dancers writhe and twist on clifftops, is a love letter to her collaborators, to constellations of care that transcend oceans. Like the figure in Dark Light, who shares these dancers’ unashamed sensuality, the human body is inseparable from the social body. It moves, speaks and resists. And it finds solace in other people.

This is also the case for Gurrutu‘mi Mala – My Connections (2019), a spellbinding video by Gutiŋarra Yunupiŋu, a twenty-one-year- old Yolngu filmmaker with hearing loss. Like all Yolngu children, Yunupiŋu, from East Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory, was taught Yolngu Sign Language, a now-endangered ritual dialect. In the work, the image of the artist appears ten times. Each version performs a sign, drums in the background recalling heartbeats, lifeforce. Words might elude him, but his connection to his ancient language means that he can still speak clearly to those who can understand.

The works in Wansolwara are rooted in the specific. But they also rail against the scourge of authenticity. ‘There are no true interpreters or sacred guardians of any culture,’ the great Samoan poet Albert Wendt wrote in his famous 1976 essay ‘Towards A New Oceania’. The exhibition takes this edict seriously, mining unlikely connections between people and finding lineage between places we don’t expect.

On the ground floor of 4A is Auckland artist Rebecca Ann Hobbs’s South (2010–11), a series of videoworks that see members of South Auckland’s Pacific Islander community dance on bridges, in industrial spaces and in shopping malls. They borrow their moves from vogue and dancehall, forms conceived in 1980s Harlem and 1970s Kingston that have crossed the Great Ocean and jumped time and space to give voice to the struggles faced by Pacific Islanders decades into the future. The dancers strut, pop and roll, their movements electric and deliberate. Bodies can be misunderstood, underestimated. But they can also use old language to create new spaces and dream up new ways to be free in the process.

Wansolwara: One Salt Water, UNSW Galleries and 4A Centre for Contemporary Art, Sydney, 17 January – 29 March 2020

From the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia