From Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers to Weather Report, the saxophonist and composer put the language of jazz under the microscope, then dissected it

By the time – in the mid-2000s – I began encountering the revered saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter, who has died aged 89, live in concert, he already had behind him a long and distinguished history. He had recorded a landmark set of records for the Blue Note label during the 1960s and 70s; had replaced John Coltrane in the Miles Davis Quintet; had helmed the jazz-rock fusion supergroup Weather Report; was generally considered a guru and a sage. Yet onstage, Shorter wore that history very lightly.

One gig, at the Barbican in London, took longer than was decent to take flight. Shorter, with a pained expression on his face, kept switching between his soprano and tenor saxophones, until eventually he wrenched out of the air a promising-sounding melodic nugget. It was the shot in the arm the performance needed, and the audience roared their approval. Another concert, at London’s Royal Festival Hall, found its purpose and momentum from the first note, as the four musicians interlocked like delicate clockwork mechanisms – each apparently going tick-tock at a different speed. The point being, Shorter was prepared to countenance the hesitancy of the first gig to achieve the white-heat creative spontaneity of the second. Handing his audience music he had already worked out – putting on a show – was a complete anathema to him.

Born in 1933 in New Jersey, Shorter came from a generation of saxophonists – including Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Pharoah Sanders – who put the language of jazz under the microscope, then dissected it. In his 1989 autobiography, Miles Davis explained that Shorter had ‘always been someone who experimented with form instead of someone who did without form’. In a 1995 interview for the BBC, Shorter himself compared the inner-workings of his music to language: ‘I want to start sentences without capital letters, leave ‘i’s undotted, demolish full-stops and semi-colons and distort the grammar’.

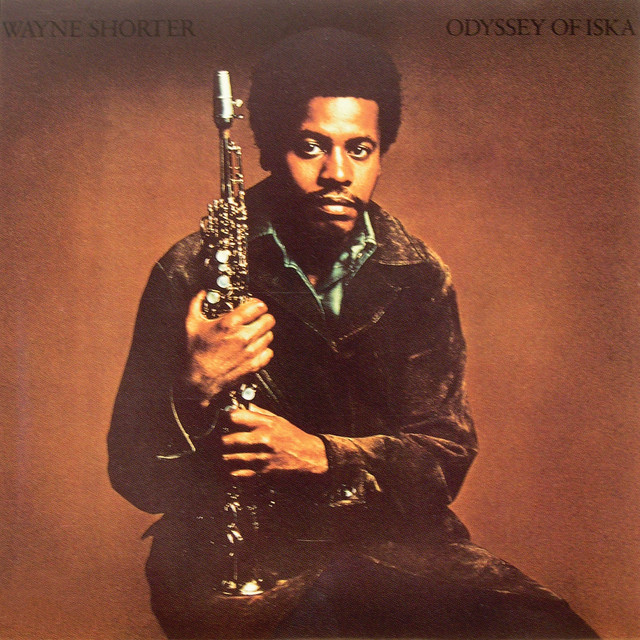

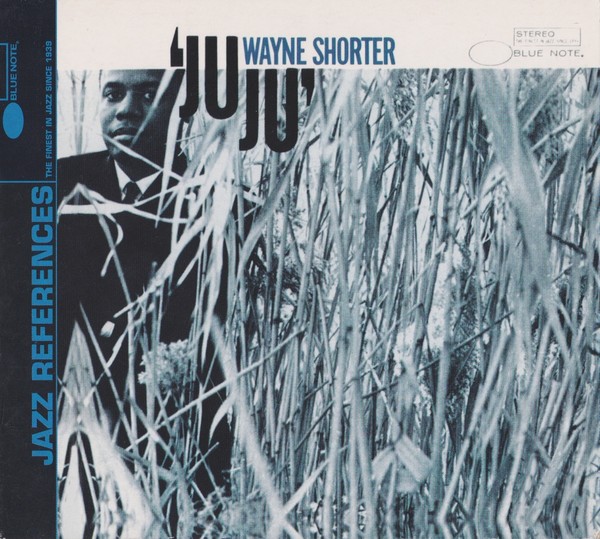

Miles also observed that Shorter’s first big job in jazz, joining Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1959, had represented a double-edged sword: ‘Wayne had been known as a free-form player… he wanted to play freer than he could in Art’s band but he didn’t want to be all the way out’. The sequence of eleven albums Shorter recorded for Blue Note, beginning in 1964 with Night Dreamer and Juju and ending with Odyssey of Iska in 1970, squared that circle. That the majority of these albums – Speak No Evil, The Soothsayer, Etcetera, The All Seeing Eye, Adam’s Apple – spilt out in an eighteen-month creative mad-dash speaks of how urgently Shorter needed to follow his muse. Night Dreamer was recorded with the rhythm section (McCoy Tyner, Reggie Workman, Elvin Jones) of John Coltrane’s classic quartet and the debt is obvious; however Juju, made only a few months later with the same musicians, is convincingly a ‘Wayne Shorter Quartet’ album, not Shorter with Coltrane’s players.

The title track of Juju illuminates the essence of Shorter as composer, where deceptively simple melodic cells generate steam by moving forwards then rewinding back on themselves; this theme feels collaged and spliced up, with any superfluous note or harmony curtly dismissed. ‘Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum’ from Speak No Evil messed with the grammar in another way, by presenting all the development and variation first, and only then revealing the theme itself. In The All Seeing Eye (1966), Shorter dissembled the expected format of jazz albums – as sequences of openers, blues, ballads and standards – by presenting a through-conceived 50-minute structure, in which improvisation and composition operated as equal partners. Like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (1965), The All Seeing Eye was a meditation on existence and creation in which structures, harmony and textures crumbled, were overlayed – and hurtled into each other.

Shortly after Shorter’s Blue Note career ended came the release, in 1971, of Weather Report’s eponymous debut album. Shorter had been a key creative partner on those late 1960s/early-70s Miles Davis albums – Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968), In A Silent Way (1969) and Bitches Brew (1970) – in which the trumpeter embraced the grooves and the electronic paraphernalia of rock music, and Weather Report pursued those challenges in new directions. The mantra of the group – ‘nobody’s soloing, everybody’s soloing’ – was indicative of a finespun weave of improvisational voices playing together, an approach that became the group’s calling card. There were those who thought Shorter’s talents as a soloist were being swamped and, perhaps in response, he started playing the old Bob Hope number ‘Thanks For The Memory’ unaccompanied in their concerts – typically, probing the outer limits of its harmonic scheme.

Shorter also put in regular appearances on Joni Mitchell’s albums and lent his sound to Steely Dan’s Aja (1977). Although his later years were scarred by two shattering tragedies – the death of his daughter Iska, from a seizure in 1985, and of his wife Ana Maria in the TWA flight that crashed in Long Island in 1996 – he always radiated infectious optimism. His late-period quartet, the one I witnessed in action, became a fertile laboratory for his ideas about sound and structure; and when health problems meant he could no longer perform, he ploughed his energies into creating an opera, Iphigena (2021), in collaboration with bassist Esperanza Spalding who provided him with a libretto. His all-seeing eye never dimmed.