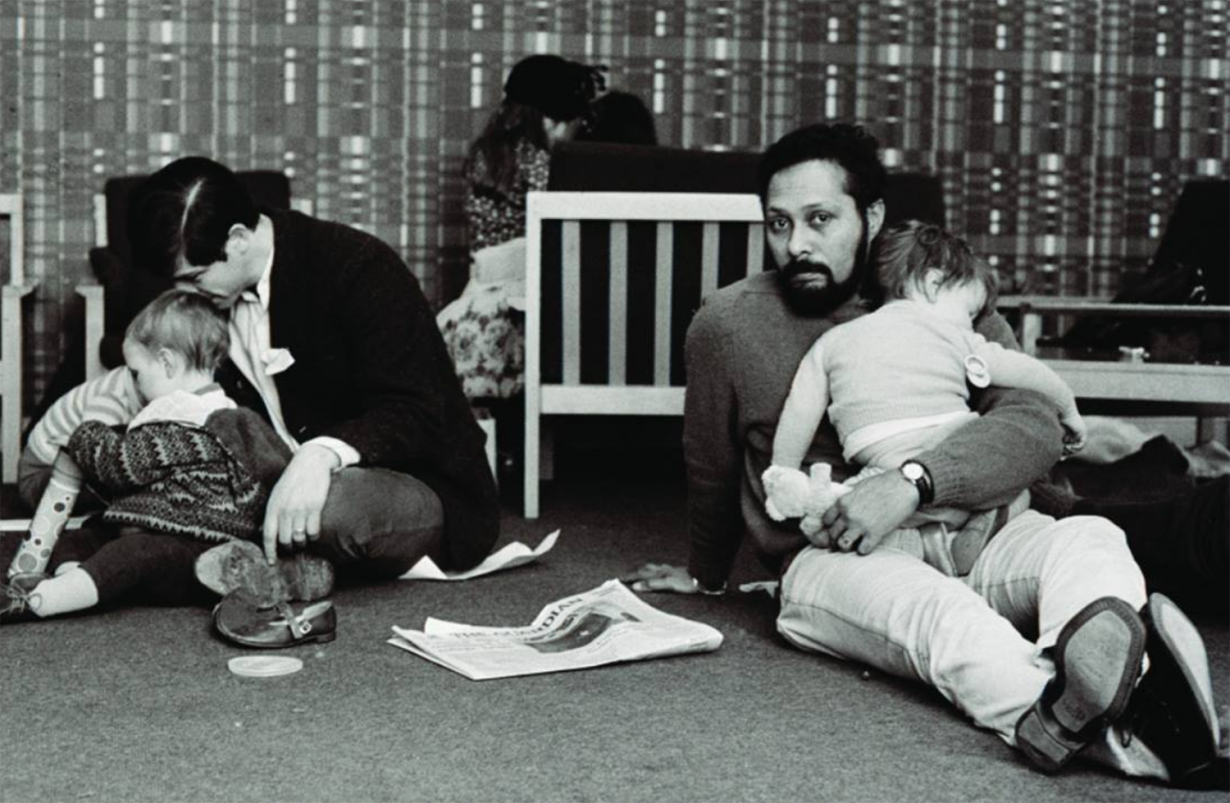

Writer Tom Whyman and his two-year-old son visit artist Albert Potrony’s ‘non-hierarchical’ crèche at the BALTIC gallery

I don’t think I fully appreciated this until I had kids. But what you need to know about art galleries is, that they are playgrounds. People think of ‘an art gallery’, and they think of some staid white cube where people go to stroke their chins or start tentative romances while feeling some very profound feelings and thinking some very profound thoughts. But actually, in my experience – especially my more recent experience – art galleries are big, fun, ecstatic spaces where Material is shown in its most alive, most basic, most joyous form: as Stuff you can use to Create. And they’re full of families of screaming children, running around like maniacs. Or at least this is how it seems to me, whose horizon of experience, at the weekends, is typically dominated by a single, wonderful maniac: my two year-old son.

If this is not true of all art galleries, then this is at least true of big, public galleries like the BALTIC – local to me on the Gateshead side of the Tyne – which have their social function primarily as spaces where you can take your kids for free when it’s raining. This became especially obvious to me during the two big lockdowns in the UK, when the BALTIC was closed and there was suddenly nowhere, save the park, to go. It was thus with great excitement that I saw that the gallery has chosen to welcome the return of at least most of the old freedoms with equal play, an exhibition by the artist and educator Albert Potrony, which features – alongside a number of educational resources, mostly pertaining to the ‘anti-sexist men’s movement’ of the 1970s – a room full of what are essentially the detached, deconstructed elements of a soft play centre, or a playground: foam cylinders, planks with holes in, bits of rope – which both children and adults can use to construct their own ideal play-space together, and at will. (In general BALTIC is very good at this kind of thing – another exhibition currently running, Ad Minoliti’s Biosphere Plush, includes a space where one can sit and do some colouring in).

The idea behind Potrony’s piece, which is inspired by the radical Dutch playground designer Aldo Van Eyck, is to allow for ‘non-gendered and non-prescriptive play,’ dissolving the sorts of hierarchies associated with the traditional masculinity that the anti-sexist men’s movement had been set up to oppose (among the movement’s concrete actions was to run the nursery at the Women’s Liberation Movement conference – with Stuart Hall on crèche duty). Van Eyck’s playgrounds, few of which survive today, focused on abstract forms like arches and mounds (as opposed to just slides and swings), and were never cordoned off with fences: the idea was not to ‘dictate’ play, and border it off, but rather to set it free – to let children play however they wished, and for that play to then spill out unbounded into the (adult) world. Potrony’s exhibition makes explicitly transparent the political implications of this way of designing spaces to play.

All of this sounds great to me (well – the ‘no fences’ thing is a bit of a worry in a world where I have to keep a guy alive who often seems to want to run headfirst into traffic, but you know: I get what Van Eyck was trying to do in theory). But I did have one specific worry, when I took my son: would equal play pass ‘the lift test’?

Probably you do not live in a world where ‘the lift test’ is any sort of concern. But I do. Because the thing is, whenever I take my son to the BALTIC, which he loves – whether we’re in a gallery, or on the second floor that’s largely given over to kids’ play – there will always come a point, sooner or later, where he decides that really, what he would prefer to do, is to go up and down in the lifts. In the BALTIC, the lifts are very big, and prominent: glass boxes from which you can see out of the windows, all the way up and down the building. They make noises, and have buttons, and it feels kind of funny when you’re going down – my son simply cannot get enough of ‘going in the lifts.’ (I, by contrast, do not really like going in the lifts. I find lifts in general claustrophobic, and I find it embarrassing to be going up and down in them all afternoon, looking – albeit accurately – like someone who struggles to discipline their child. He could go on the lifts all day. I, by contrast, would always opt to limit myself to one journey in the lifts or less).

So to me, really, the central question was: would Potrony’s art-playground actually be able to seize my son’s attention (and imagination)? Or would he just sort of immediately decide he wanted a go in the lifts instead? Would this be more fun than going in the lifts, or less?

Well, the results are in. I took my son to equal play last month, and the answer – unfortunately – is no. Albert Potrony’s equal play is not more fun than going in the lifts. At best, equal play is an intriguing supplement to an otherwise predominantly lift-based art gallery day. But in a way, conceptually, that’s fine.

During our visit, we went to equal play, which is installed in the ground floor gallery, twice. Initially, the first time, the results seemed promising. When he saw the space, my son’s face lit up – as if he knew that this space was for him. He was immediately curious about the big rubber cylinders, which he started trying to climb up – moving smaller cylinders into place so he could get up onto the big ones, while I clowned around pretending to get things wrong. It was a lot of fun. But it couldn’t last. The problem is that from equal play, at all points, through the wide-open entrance, you can see the lifts. So whenever my son turned his head away from the cylinders, there they were – the lifts – tempting him. ‘Just one push of my buttons,’ they seemed to say. ‘Just one little trip up. Just now. It doesn’t matter where you’re supposed to be. I’m here.’

And so we ended up spending most of the afternoon on the lifts – alternating with the more traditional second floor playroom, where my partner was sitting with our newborn daughter; my son gravitated to some wooden animals, telling us which was a deer, and which a bear. A perfectly nice way to spend a Saturday with young children, all told, but still – I’d had much higher expectations of the actual exhibition.

The problem, it seemed to me, was that none of the equipment in equal play was sufficiently anything. It’s all well and good to allow children to play with planks and shapes and stuff, in a ‘non-gendered’ and ‘non-prescriptive’ way. But play is already non-prescriptive: when children play with the various objects they choose to, they already project their imaginations onto them in all sorts of different ways. When a child plays with a toy, they are not only playing in ways the toy demands – it is a negotiation. Some children will be given a toy car and pretend to brush its teeth and put it to bed; others will be given a doll and decide to launch it as far as they can into the air.

And yet – the object-side of this is important too. Children use play to explore the world – and this does mean it’s important for them to be able to place their toys in certain familiar categories, that they’re then able to navigate. My son likes animal toys because he can tell us what they are (and then they can pretend to ride the train and go to visit his auntie); he’ll always go on a slide, or on a swing, because he knows what you’re supposed to do on them. He likes things with buttons – like the lift – because he knows that when he pushes the button, it will do something: that he will bring about a particular, predictable effect. Tellingly, what most of the other families in equal play were doing, was using the non-swing and non-slide bits of play equipment (ropes, planks, foam shapes, etc.) to assemble ad hoc swings and slides. Adults feel like the prisoners of concepts and categories and regular routine – children are still desperate to master them.

But these were only fleeting thoughts. Eventually, after an hour or so in which I was brooding internally on the exhibition’s failures, my son and I found our way back. And this time, he found some rope. The length of rope he found, lying on the floor detached, was about two metres long, and colourful. He held one end – unable to comfortably carry it all himself, he handed me the other. And then we ran. Sometimes I was in front, and he was having to keep up; sometimes he was, guiding us comfortably around the gallery floor. “Are you walking daddy?” someone else in attendance asked us, as he led me out of equal play itself, and into a fire door. I dragged us back, then we went round again, and again, and again – giggling at the tension in the rope between us, laughing at the audacity of our connection through this thing.

And suddenly, there it was – the exhibition worked. Here we were playing with the rope in a non-prescriptive way, dissolving in the moment the hierarchies of father and child that normally structured all of our interactions. Equal play might well have failed the lift test. But in a way, I thought, that only proved Potrony’s point. True play cannot be contained in a single gallery. It must spill out from the playground itself – into the lifts, onto the viewing gallery on the fourth floor; onto the streets of Gateshead quays. Equal play could never have passed the lift test, and still stayed true to its ideals – because to have passed the lift test, would have meant bringing play itself to a halt.

Albert Potrony, equal play, BALTIC, until October 2022.