In Lives Less Ordinary, a diverse portrait of working-class life offers welcome respite from the patronising photographs of Martin Parr

Two boys with dirty knees and linked arms gambol down a Glasgow street, both looking directly into the camera. The English photojournalist Bert Hardy took this grainy black-and-white photograph of a postwar urban scene, titled Children of the Gorbals (Gorbal Boys), as part of an assignment for the Picture Post in 1948. The magazine had tasked him with capturing images for an article about poverty in the city’s cramped tenements. Though it was Hardy’s favourite shot, the editors rejected it – because the subjects are smiling.

Whether shown in publications or art galleries, documentary photography often serves the function of revealing the harsh reality of working-class lives to middle-class audiences. Typically, the ‘grittier’ the scene, the more realistic these audiences deem it. We are used to seeing working-class people and places in relation to discussions around social issues. We might expect a film set in a northern city, for instance, to be about how oppressive life there is (think of the 1960 social realist film Saturday Night and Sunday Morning). Whereas middle- and even upper-class settings are the default: neutral backdrops for dramas about anything else. This is a matter of underrepresentation as much as misrepresentation; we lack depictions in art and culture of working-class people experiencing the full range of life – good, bad and everything in between.

Hardy’s photograph is one of the first works you encounter in Lives Less Ordinary: Working Class Britain Re-Seen at London’s Two Temple Place. The exhibition’s curator, Samantha Manton, notes in an accompanying essay that, in culture and media, ‘working-class life is frequently characterised by crisis, poverty, insecurity and dispossession’. She aims to challenge this one-sided view by bringing together the strikingly varied work of more than 50 British artists working across photography, painting, sculpture, film and ceramics, from the 1950s to the present.

‘I wanted to make the ordinary miraculous,’ the Sheffield-born ‘kitchen sink’ painter Jack Smith once remarked. ‘This had nothing to do with social comment. If I had lived in a palace I would have painted chandeliers.’ The ‘kitchen sink school’ of painting, a much-debated label coined by the critic David Sylvester, was held up by his contemporary John Berger as offering ‘a sharper meaning’ to working-class reality. Yet in a review of Lives Less Ordinary, the Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones questions whether Smith’s 1954 painting Interior with Child, a comfortable domestic scene of a little girl playing with a dog, really counts as working-class because ‘… it could as easily be a middle-class home in austerity Britain as a working-class one’. Assessing the exhibition, he protests that ‘working-class authenticity keeps spinning away as you look’.

Class has a tendency to do that – to twist away when you try to pin it down. What does it look like, and who is doing the looking? Is it a matter of cultural identity or financial status? Can it change over generations, and even within a single lifetime, or is it something you carry with you always? During the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher set about dismantling heavy industry in the UK, declaring war on trade unions and working-class communities. In 1992 her successor John Major offered the dubious promise of ‘a classless society’, and a few years later New Labour’s John Prescott declared that ‘we are all middle class now’ (we weren’t). Working-classness has only become more difficult to define – despite the fact that in 2025, after 15 years of austerity (and counting), inequality is rife and social mobility stalled.

When Jasleen Kaur (who was raised in a Sikh family in Pollokshields, a historically working-class area of Glasgow) won the Turner Prize in 2024, she reflected in her acceptance speech on her lack of cultural access to the artworld in her childhood. The chances of seeing another working-class artist’s work in the Turner Prize in the future are growing slimmer. For a young working-class person today, the barriers to becoming an artist are enormous. According to a 2024 report by the Sutton Trust, there are around four times as many younger adults from middle-class than working-class backgrounds currently working in the creative industries.

Some of Kaur’s playful assemblages of found objects are in Lives Less Ordinary. He walked like he owned the place (2018) comprises a white plastic chair draped in a neon orange tracksuit with a blue band that looks (at first glance) to be sports branding; it is actually embroidered with the kirpan, the khanda, and the chakkar – weapons that form the Sikh emblem, a symbol with a colonial history. Kaur draws a line of connection between the sportswear popular with young working-class people during the 1990s and her religious background. We are in a moment when politicians and journalists have once again started to throw around the divisive term ‘white working class’, talking about race and class as though they are mutually exclusive. Kaur is just one of the artists in the exhibition whose work speaks to the intricacies of cultural identity – giving lie to the idea that working-class communities are homogeneous.

Lives Less Ordinary foregrounds playfulness and joy over solemnity and suffering – without trying to sweep hardship under the carpet. Kelly O’Brien is an artist and researcher who grew up on a council estate in Derby. Descended from a long line of cleaners, she describes the women in her family as being ‘intergenerationally absolutely knackered’ – a legacy that she makes visible in her witty installation in the exhibition. Visitors can pick up a CV and see the unpaid and low-paid jobs of her grandmother and mother overlaid with her own. The CVs are stacked in front of a huge screen: on one side there’s a print of O’Brien’s mother in a cleaning tabard, ‘NO REST FOR THE WICKED’ emblazoned in pink letters across her chest, feet strapped to bricks, her face covered by a pink mop. Her pose here is heroic, in a piss-taking way, but the reverse of the sheet shows her bent over double with exhaustion, illustrating the impact years of labour have had on her body.

While O’Brien makes working-class women’s undervalued labour visible, the final section of the exhibition celebrates leisure and pleasure, and includes paintings by Beryl Cook. Despite (or because of) her popular appeal, Cook was long dismissed by the artworld, her libidinous paintings of voluptuous working-class women enjoying themselves considered bad taste. It seems that a reappraisal is now underway, with Studio Voltaire placing Cook in a joint exhibition with Tom of Finland in 2024, in what was the most-attended exhibition in the institution’s 30-year history. As the scholar Jennifer Jasmine White pointed out in a 2024 essay, ‘the dynamic between the lower-middle-class Cook, well-spoken but reserved, and her loud, confident [working-class] subjects remains a complex one’. There is undeniably a voyeuristic element to Cook’s gaze – to what extent was she an outsider looking in?

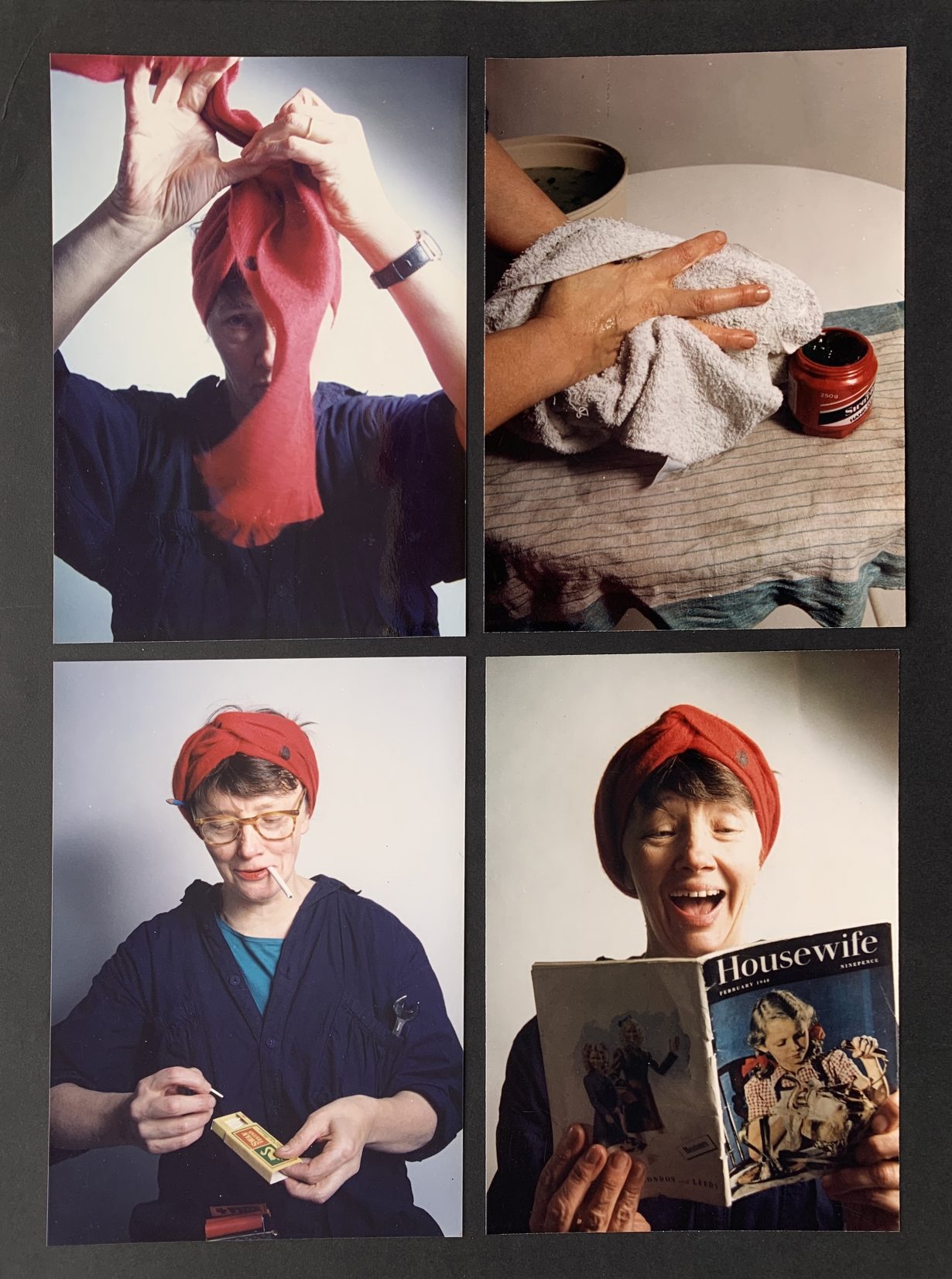

Most of the artists involved in Lives Less Ordinary are working class. In this sense, they have insider perspectives on working-classness, as opposed to being distanced observers. The feminist artist Jo Spence explored this insider/outsider dynamic in her photography, reflecting that she had been ‘taught to be ashamed’ of her factory-worker mother as she had moved away from her working-class roots and into the middle-class artworld. In the photo series The Mother (1984), Spence employed what she called ‘photo-therapy’ – a combination of counselling, acting and portrait making – to capture herself playing her own mother. Turning the camera on herself allowed her to empathise and feel solidarity with her mother while avoiding being a voyeur. Spence regarded herself as a ‘cultural sniper’, taking aim at the classist and sexist art establishment from the outside.

One notable absence from the exhibition is Martin Parr: the Surrey-born middle-class photographer who is the subject of a recently released documentary film by Lee Shulman, I Am Martin Parr (2024). Parr’s most recognisable work is perhaps his Last Resort series (1983–86) – photographs he took during the 1980s of the Liverpool beach resort of New Brighton. In a number of ways, this work marked a radical departure from the conventions of the time. For one thing, their garish, oversaturated colour was typically associated with commercial photography. For another, he was capturing scenes of working-class leisure – without clear political intentions. “There’s a certain degree of politics in my work,” he says in the documentary, “but I’m not telling people what it is… my main project is the leisure pursuits of the western world, in all classes.”

While it is true that Parr has focused his lens on middle-class subjects as well, his photos of working-class people are infamous. Where some see satire of consumer culture, or an innocent eye for eccentricity, others see patronising mockery. Personally, I find Parr’s photographs more uncomfortable than amusing. I feel as though I am being encouraged to see the people in them as archetypes rather than individuals with inner lives. He catches people at awkward angles, in absurd moments, sunbathing surrounded by rubbish, ice creams melting. How does it feel to be in the glare of his flash? Can you recognise yourself? In one photograph, a woman lies shielding her eyes from the sun, while a baby in a pushchair screams behind her, seemingly ignored. In the documentary, Parr recounts a moment when the woman in the photo came up to him when he returned to New Brighton for an exhibition in 2018. “She kept saying, ‘This is not my kid.’ He was someone else’s apparently, who she was looking after, briefly.”

Writing about Last Resort when it was first displayed, the critic David Lee commented: ‘Our historic working class, normally dealt with generously by documentary photographers, becomes a sitting duck for a more sophisticated audience.’ The film emphasises the humour in Parr’s work, presenting it as an antidote to the self-regarding seriousness of traditional documentary photography – but who is the joke on? Everyone involved in the documentary clearly knows that Parr’s work elicits strong reactions, and while the tone is lighthearted, there is a strong undercurrent of defensiveness. “A lot of humour is seen as cruel, but I never think Martin’s photos are cruel,” says actor and comedian David Walliams, who appears as a talking head. Walliams cocreated Little Britain, the early-noughties comedy sketch series that used classist, racist and ableist tropes for laughs, including a ‘chav’ teen mum character, Vicky Pollard. In 2020 it was removed from all UK streaming platforms due to concerns about the use of blackface by its two stars, including Walliams. He does not seem like the best person to ask.

A large part of the documentary consists of footage of Parr on a return trip to New Brighton. Now in his seventies and recently recovered from illness, Parr moves slowly through the crowds with the aid of a walking frame, frequently pausing to take pictures. At one point he photographs two young women working behind the counter in a café. Understandably, they start to laugh nervously, smiling for his camera. ‘Now can I do one of you being serious as well?’ he asks.

Anna Coatman is a writer and editor based in West Yorkshire