Or why the first-person exhibition review hit the mainstream

A few years back, when I was teaching a class on art criticism in Salzburg, one of the participants said something that’s stayed with me: that art critics, as they get older, tend to use the first person more. On the one hand, I think that’s true – see this very column, or any of the earlier ones – and is something to do with confusing having your sketchy opinions published for years with them mattering much. For a useful corrective, a critic might pay attention to where they’re placed at the gallery dinner; enjoy getting to know the technicians. On the other hand, grizzled art writers starting every other sentence with ‘I’ are no longer the exception. If anything’s changed in art criticism within living memory, aside from the latter-day ‘crisis’ it seems continually able to stagger through, it’s that the first-person exhibition review has mainstreamed.

Now, I’ve commissioned reviews at ArtReview for years, and not too long ago, if someone filed copy in the first person I’d be like, ‘no’. It wasn’t just me: I remember a (relatively) lively letters-page exchange in another art magazine because a critic had prefaced his exhibition review with thoughts from a book that, he said, he’d happened to find on the train to the show. But when virtually everyone – especially younger writers – is putting themselves front and centre in the text, and given that cultural forms (including relatively lowly ones like criticism) aren’t meant to be static, you have to ask if you’re right or they are.

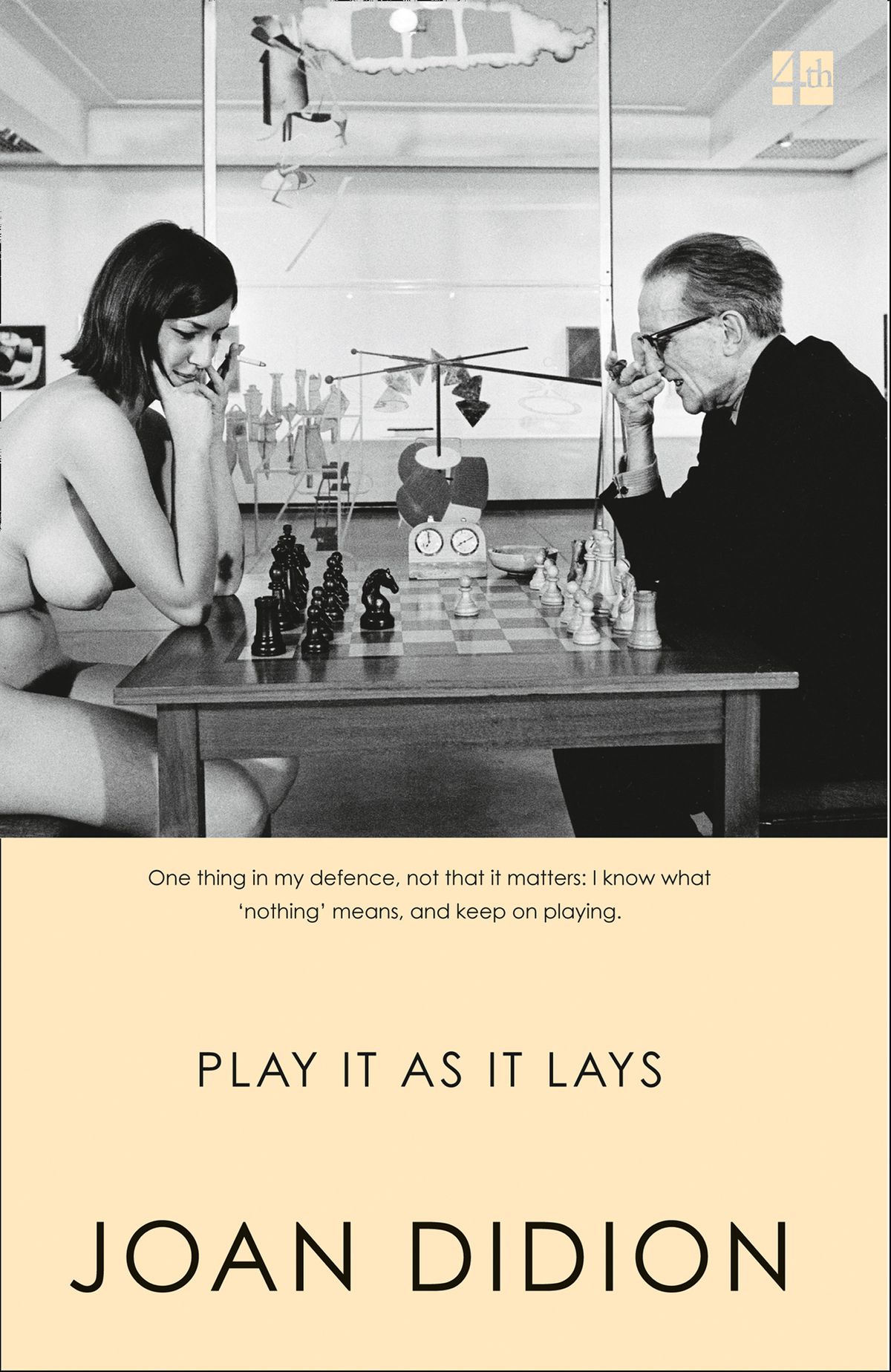

Of course, first-person journalism, if not so much first-person criticism, is not new. It goes back at least to the Victorians, was updated (with, as Dave Hickey said, ‘neon punctuation’) by the so-called New Journalism of the 1960s and ‘70s and hasn’t really gone away since. Last month my social media feeds were full of responses to the death of Joan Didion, a key exponent of the latter style, and they made it clear that she was a figure of influence for a lot of people in the artworld. Count the number of Instagrammers posting the cover of a recent reissue of her 1970 novel Play It As It Lays, with its oddly chosen image of Duchamp playing chess with a nude Eve Babitz – the Los Angeles novelist and sort-of rival of Didion, who died, spookily, a week before her. (My first edition of The White Album is in storage, so I couldn’t flaunt it.) Anyway, when I began reading Didion – in the ‘90s, after writerly critics like Bruce Hainley kept shoehorning her into their texts – and her forensic accounts of her own reactions to the world, I thought, ‘I can’t do that’. But that was before blogs, and then social media, and the concomitant rise of the ‘personal essay’, encouraged everyone to see themselves as the centre of their own unique drama, and self-exposure became entangled with likes and squirts of dopamine.

As an editor working with various generations of contributing writers, I’ve seen this situation morph and complicate, with mixed results. Once it’s established that you’re talking about your experience, maybe you think it’s okay to talk about the private view too, or the conversation you had there with the artist. Maybe you want to quote them; maybe the review then ends up being partly your opinion of the work and partly the artist’s. I typically put my foot down there (not to get into the whole conversation about the ‘critical’ element of critical writing, and the fact of writers who are also freelance curators, etc, trying to play nice.) Then I go and see a show myself on a rainy day, or hungover, or after train delays, and don’t like said show, and wonder about objectivity.

On the upside, and relatedly, one thing that might feel appropriate about this centring of ‘me’ is the implicit avowal, or admission, of subjectivity in the critical act. Just as, in a substantial amount of twentieth-century criticism, the creator’s intentionality was discounted, now what’s emphasised is that one person, one ‘I’, saw this, and these are their thoughts on the art and whatever else flows across the brainpan. Some art writers who publish primarily online, and are freed from word counts, accordingly set off on untethered odysseys into how a given show made them feel (the current cultural emphasis on prioritising our own feelings isn’t irrelevant here either). Sometimes this leads to good and even great writing, sometimes not; but if you try and wish away this refraction of art through the prism of the self, you’re probably Canute. In any case, nothing lasts forever and, probably, anything is preferable to the bought-off pabulum pumped out by gallery-owned magazines. Plus, in each moment of reification there’s an opportunity. Obviously, we’ve had – and still have, in abundance – first-person art writing. We’ve had second-person art writing, in which the critic empathetically imagines ‘you’ experiencing the show (second-person writing was a Didion speciality, too, and Peter Schjeldahl has also done this a fair bit). Want a challenge, scribe? Third-person art writing.