The desire to have done with the past – not only its history but also its thought – comes at a cost

Contemporary critical theory often recalls nothing so much as a bad trip – everything is connected, but nothing means anything. The well-meaning (or perhaps anxious) attempt to incorporate the perspectives of every entity, living or dead, be it identity-group, nonhuman plant or animal, indigenous knowledge or disciplinary insight, culminates, ultimately, in a tepid literature review, an artworld-friendly glitter-bomb of the ‘right line’.

So it is with philosopher and feminist Rosi Braidotti’s new book. Braidotti seeks here to build on two of her previous works, The Posthuman (2013) and Posthuman Knowledge (2019), as well as her lengthy feminist commitments. Posthuman Feminism is thus partly a qualified defence of posthumanism – the idea that the human is being redefined by technology – combined with feminism, which, according to Braidotti, is the ‘struggle to empower those who live along multiple axes of inequality’. This definition of feminism is fashionably broad, incorporating ‘ecofeminism, feminist studies of techno- science, LGBTQ+ theories, Black, decolonial and Indigenous feminisms’. All of this in the context of the ‘Anthropocene’ – the era when homo sapiens has irreparably transformed nonhuman nature – and ‘increasing structural injustices’, ‘devastation of species’ and ‘a decaying planet’.

Technoscience is a double-edged sword of course, producing all manner of horror, as well as some exciting new possibilities. It might have ‘subversive potential’ when it comes to gender identities (which are potentially ‘bio-hacking the future’), but it also exploits our genetic material and destroys the planet. Feminist technoscience studies, Braidotti unsurprisingly notes, is ‘often at odds with itself ’. Nevertheless, Braidotti claims, posthuman feminism is a better lens for analysing power than competing perspectives because it has ‘relinquished the liberal vision of the autonomous individual as well as the socialist ideal of the privileged revolutionary subject’.

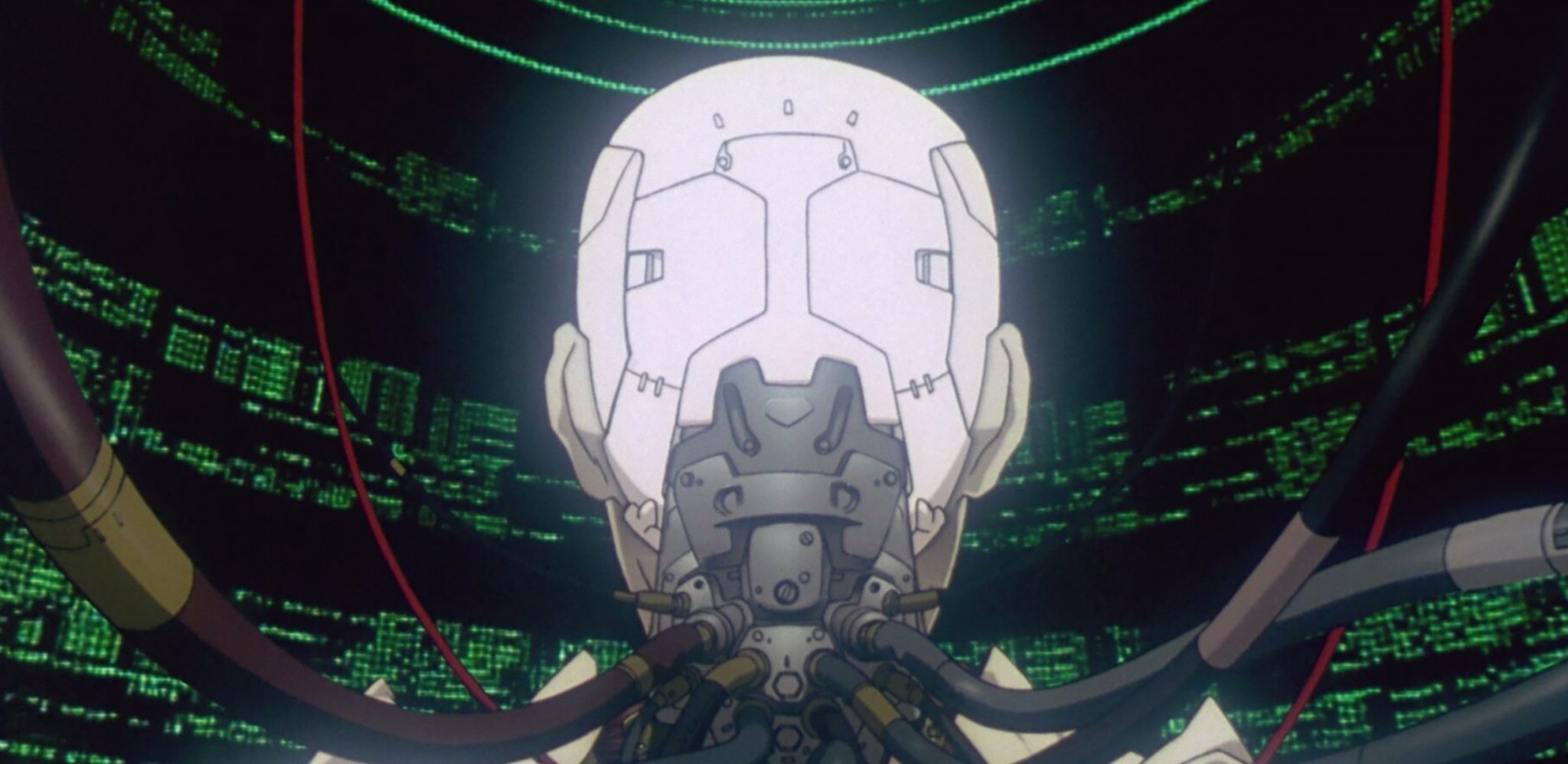

While Karl Marx will be turning in his grave at the idea that the class with ‘nothing to lose but their chains’ is somehow ‘privileged’ (perhaps she means privileged in the discourse, rather than in reality), and we might wonder what happens when we give up on the individual (must we upload our souls to the Borg, Daddy?), the main thing is to move beyond ‘Western humanism and anthropocentricism’. This desire to have done with the past – not only its history but also its thought – comes at a cost, however.

What is absent here, beneath the attempt to represent all right-thinking perspectives, is much argument. We are told, for example, that binary oppositions act as ‘instruments of power and governance’, but not why we should give up on binaries as such. Underpinning Braidotti’s assertions is a set of now-familiar assumptions – that Eurocentrism exists and is bad; that the Enlightenment was a cover story for barbarism; that ‘Man’ ultimately means ‘white man’ – that are not questioned in their depths. At moments Braidotti acknowledges that these legacies are contested, before returning to familiar and ritual depictions.

In her bid to separate posthumanism from bad transhumanism, for example, where the latter position remains indebted ‘to the Enlightenment project of social and political emancipation’ and to ‘liberal individualism’, she comes close to recognising some of the tensions of her own perspective: ‘the sheer reliance on technological mediation and the pursuit of a project of perfecting embodied selves through science and technology, brings queer and trans theories paradoxically closer to the Enlightenment project’. So which Enlightenment is it to be? Picking the one you like seems itself to be awfully dependent on a liberal notion of individual choice. Braidotti’s vision comes in peace (‘What is ultimately at stake is a sense of futurity and love for the world’), but remains beholden to a theoretical and political eclecticism that lacks philosophical depth – perfect for today’s fuzzy art and lazy thinking, but unable to give enough critical distance from contemporary ideology to provoke much-needed fresh thinking.