Turner Prize-winning artist Tai Shani on resisting the artworld’s rightward drift in an age of COVID-19 cuts and censorship

In July, I experienced something that made me worry even more intensely than usual about the troubled relationship between artists’ work and the institutions that ‘support’ it.

The four Turner Prize co-winners of 2019 – Helen Cammock, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Oscar Murillo, and I – were commissioned to make a collaborative work following the award. We were excited about the context of a very public space, Piccadilly Circus, and about the possibility of responding to the urgency of an extraordinary moment: the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests. Unfortunately, we had to withdraw from the project.

Cursory research about the site itself formed the basis of our work, which focused on the history of the iconic Anteros statue, also known as the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain. The statue, built in the late nineteenth century, commemorates the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, who was instrumental in the colonisation of Palestine.

Our work was taking place in the midst of demonstrations triggered by the violent death of George Floyd at the hands of US police, and the toppling of statues, in the UK and elsewhere, celebrating historical figures that persistently perpetuate white supremacy: monuments that go unnoticed and accepted; figures whose acts have been integrated into a pervasive ambient violence in which we attempt to live our lives.

Our collaborative text-based piece spoke specifically of an 1840 invasion of Palestine – specifically, the British bombardment of Akka that year – and used a direct quote from the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury referencing Palestine. This was flagged as problematic – in particular that it could potentially be perceived as antisemitic, and would potentially, therefore, given that it would be installed in a public space, be investigated by the police. We were asked if we would consider adding nuance to the script by removing terms, adding other countries to generalise it and draw it back into what we regarded as a toothless middle-ground.

The notion that the facts we relayed could be seen as problematic, or that the word Palestine – not viva Palestine, not free Palestine, not apartheid Palestine, not open-air prison Palestine – is now itself deemed antisemitic, is as ridiculous as it is dangerous. Just the word – not the bombings, the subjugation, the death, the no future, the brutality. Palestine.

We were given this specific site. We did not seek to draw historical connections. We were not interpreting. But this is the site. This is its history.

Capitulation to extended pressure, successfully driven by extremist agendas and backed by the UK government, often means that mention of the word Palestine – now interpreted by some as criticism of Israel – is off limits under the charge of antisemitism. Last year, the German parliament voted to condemn the international Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement as antisemitic. In France, activists have been convicted for staging BDS demonstrations. In an intense moment of imposed and gestural politics, I have often returned to the question: how does this reality sit with the ethical face our institutions so often want us to see when they post black squares, and call for care, empathy, and solidarity?

What does solidarity mean if it is so circumscribed, managed, and abstracted to the point of refusing to acknowledge how these struggles are all connected?

In thinking of these struggles, I’ve often returned to that powerful slogan of May 1968: ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible’. It is one of many French Situationist slogans, once found graffitied on the streets of Paris during the uprisings – a slogan that Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren would go on to adapt and print on shirts as ‘Be reasonable, demand the impossible’ in 1976. It is a small sentence brimming with revolutionary affects; a small sentence that powerfully demonstrates the big chaos energy of May 68 and its irresistibility to ‘punk’.

‘Be realistic, demand the impossible’ was the response by workers to the unimaginative plea of trade unionists during negotiations at the Renault car plant in Billancourt, France: ‘we must be realistic and not demand the impossible.’

With five direct words, the workers subtly but radically reimagined the horizon of possibility, communicating a politics that wants not only to break with conventions and bourgeois hypocritical sensibilities in the libertarian way that punk desired, but that also demands a revolutionary break with exploitative organisations of labour in the service of capital.

What is the impossible? Who decides what is impossible? This was being asked by the striking workers then, and we must continue to ask it today, every single day, in the overlapping worlds of life and work, wherever our voices can be heard.

The bewildering ethical paradoxes of the artworld have become as much part of the artworld as art itself. These paradoxes have been sustained by a façade of equilibrium, of a liberal centrist political position that has been hardwired into the operational models of galleries, museums, institutions, art schools, and art organisations.

Whether art or the artworld are possible spheres for the potential of radical politics in the first place is a very legitimate question. But it is one set to become irrelevant if the very infrastructures that assist art’s visibility continue to erode its integrity.

Artists, thinkers, writers, curators, etc., like anyone living in a capitalist world, have no choice but to be ethically inconsistent, but inconsistencies are even more explicit in our smaller artworld, and the proximity of these contradictions to our personal lives is rarely mitigated. These ethical ‘contradictions’ are institutionally framed as a necessity; never are their ideological motivations openly avowed. It is left to art workers to resolve with a ‘caring’ binary choice of ‘Take it’ or ‘Leave it’. The implications of this complicity are not the same for the ‘artist’ as they are for the ‘artwork’, which remains more vulnerable to being completely neutralised and drained of its integrity.

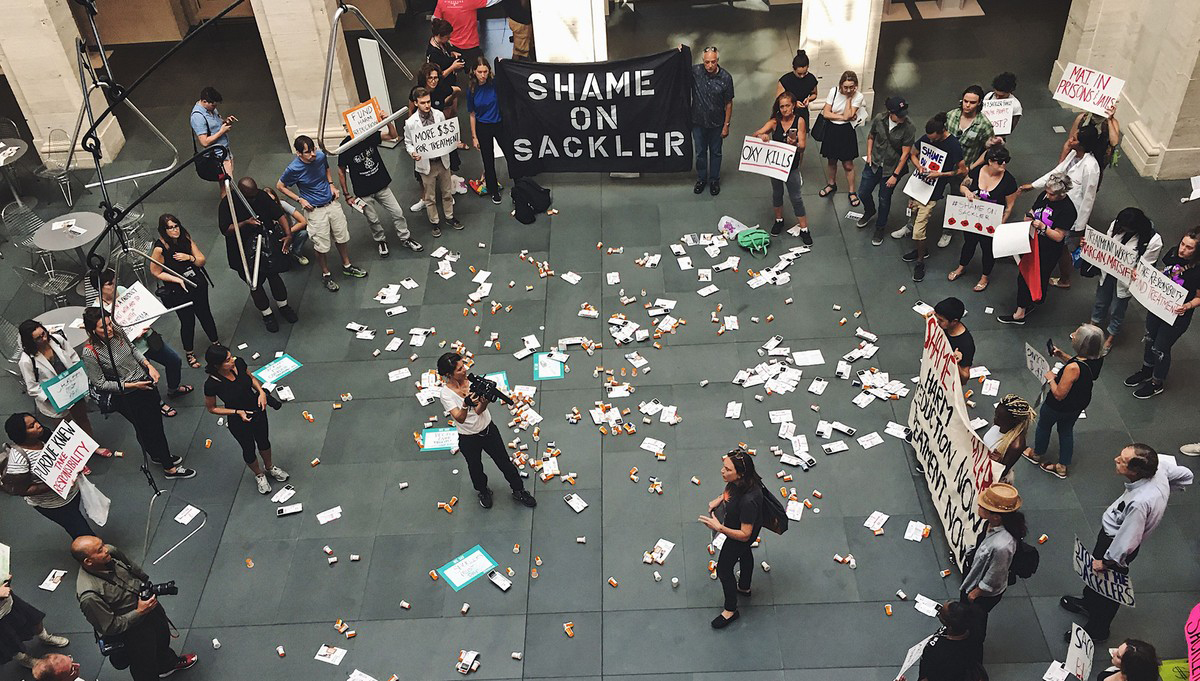

Something is changing, nonetheless: in recent years there has been increased pressure to address these paradoxes where they can no longer be tolerated. Last year heard intensifying calls for Whitney Museum vice chairman Warren Kanders, whose firm Safariland was found to be selling tear gas used at the US-Mexico border, to step down; Sackler buildings and galleries across numerous arts institutions began to be renamed because of a campaign against certain members of the philanthropic family’s ownership of Purdue Pharma, which produces the highly addictive prescription painkiller Oxycontin – it has been alleged that the drug was falsely advertised, and has been a key driver of the US opioid crisis. These campaigns have been led by artists with ‘power’ or by groups of art workers that find power together.

Some of the damage wrought by an expansionist, market and state-driven managerial approach within museums and galleries is already clear in art schools which are no longer sites for radicality, experimentation, or for learning transformative ideas. The aggressive neoliberal business model to which art schools adhere means that they refuse to jeopardize profit, turning their faces from systemic inequality and ideological conservatism, which are, in fact, inherent to their profit schemes and stakes in property. Art schools have become expensive places rife with exploitation, where seismic decisions are made that alter the very foundation of what an arts education can offer without so much as a brief consultation with the experienced and committed, if deeply disillusioned people who teach it – those who are expected to be both full time lecturers and full time artists, while they can often barely make ends meet.

Can it please be impossible for the organisations that profit from radical pedagogies and genuinely free-thinking, leftist modes of practice not to reconcile their public-facing politics and their management. Centrism is not ideology free: it is a socially liberal position that will always side with right-wing policies under pressure. An environment, such as a museum, that refuses to be hostile to anyone is invariably hostile to certain bodies. Hostile to minoritised communities, hostile to those without generational wealth and, critically, hostile to its own workers and producers.

The politics that have made it possible for Black artists to be recognised, for queer scholarship to be taught, for disability access to be mandatory, for funding to be available to artists, for a rethinking of the canon, for women to be directors of museums, for social justice, were and continue to be radical. They were once ‘the impossible’.

Siding with the politics of a system that is completely antithetical to this progressive history is turning your back on and dishonouring it, as well as failing to recognise the fact that it is a living history. This living history remains radical in the ways it says we still deserve better, while acknowledging and living with legacies that, forged in dangerous circumstances, many of us benefit safely from now. Only some people’s material conditions have improved – there is so much more work to do.

‘Impossible’ conversations taking place in the mainstream, such as how the defunding of the police could happen, are made ‘possible’ by collective radical acts that are executed under critical conditions that endanger people’s safety and lives. These conversations are platformed by institutions that benefit from them – financially and ideologically – again in safety, with little real risk attached. The least they can do is show solidarity by aligning with the politics of the work itself and implementing concomitant, supportive changes on a structural level.

In the next few months at least 1000 art workers will be made redundant, amid the COVID-19 crisis, despite their institutions receiving millions in bailout money. Many are taking industrial action, in a bid to fight for their jobs.

The demands of the striking workers at Tate, Southbank and the National Theatre are straightforward: they are asking that their jobs be saved and that creative solutions be deployed, if necessary, to do so. They are asking for their survival to be prioritised, and for their work – so long essential to the basic functioning of the institution – to be recognised as such.

Their demands are also much more than that: it is a demand to side with us, to side with the politics that you unthinkingly exploit.

If not, you are not just saying yes to a financial model that will make 1000 of the lowest paid arts workers – which may disproportionately impact Black and minority ethnic staffers – redundant in the pandemic’s brutal financial reality. You are also complicit in acquiescing to the agenda of the right: you are siding with a politics that also says YES to austerity, YES to privatisation, YES to the normalisation of racism, sexism, homophobia, nationalism, ableism, the refutation of trans rights, and all the other reprehensible ‘values’ that ‘the right’ stand for.

How can the possible be demanded when what is deemed ‘possible’ is not even remotely adequate to address the catastrophic world we are creating? We should not be worrying about biting the hand that feeds us. It is our money. We should eat the hand, for it is a delight – much, much tastier than the boot.

Tai Shani

(With the support of Helen Cammock, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, and Oscar Murillo)