‘Dialogue’ has stifled action for decades – ridding our cities of monuments to white supremacy is about dismantling systems of oppression

It can be tricky, we learn from the rolling news coverage of COVID-19, to put your finger on the precise time and place at which a disease emerged. The same is true for the epidemiology of anti-blackness. But the task of tracking and tracing where the virus of white supremacy came from is an urgent one, not least in places where racial slavery had been part of the culture and economy, and where prejudice and violence endure. From Charlottesville, Virginia to Brooklyn and the Bronx, more than 100 Confederate statues and plaques have been removed since the 2015 Charleston church shooting (though more than 1500 remain standing). Scores of American communities have come to understand how, during a surprisingly narrow window of time between the 1890s and the 1920s, white supremacists built monuments to the heritage of slavery; monuments that sought to naturalise inequality, and to turn public spaces into hostile built environments. As the scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff has observed, these statues were never “just statues”, but part of an apparatus of racism. Statues were used to make racial violence persist. Today, their physical removal is part of dismantling systems of oppression.

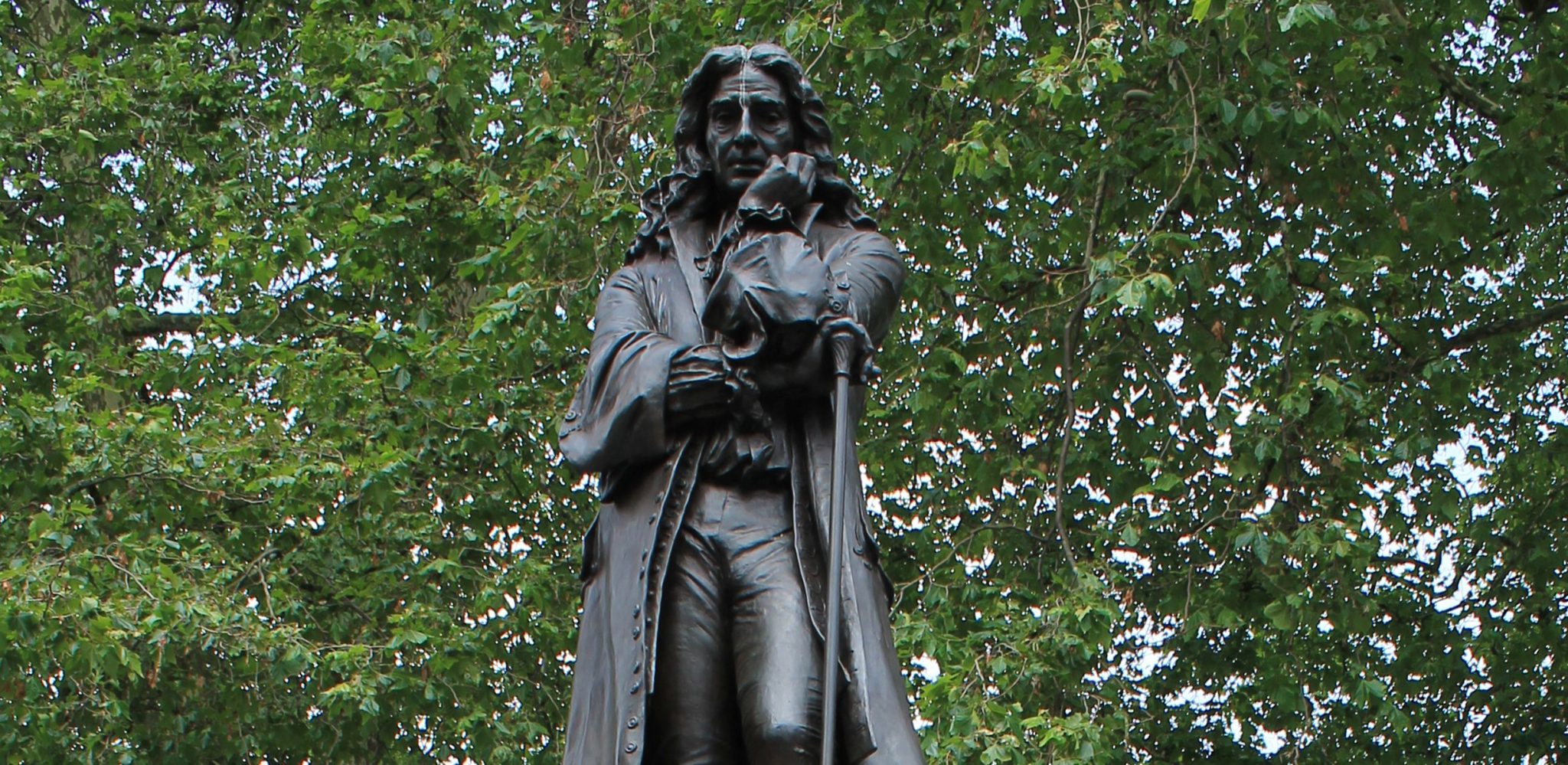

In the wake of last month’s racist killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, on Sunday 7 June the Fallism movement reached Bristol, in the UK. Calls and protests for the removal of the city’s statue of seventeenth-century slave trader, philanthropist and Tory MP Edward Colston had been continually made since the 1990s. Originally commissioned from Mancunian sculptor John Cassidy by a coalition of four local mercantile groups chaired by Michael Hicks Beach – Chancellor of the Exchequer and Tory MP for Bristol West – the bronze figure of Colston with rod, wig, and velvet coat was erected in November 1895, just a few months after the coalition Unionist government came to power. This was a government that oversaw a virulent intensification of British military violence in Africa, including the Ashanti War of 1896, the Benin punitive expedition of 1897 and the Battle of Omdurman in Sudan in 1898. At a time in which Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company and George Goldie’s Royal Niger Company were leading this new ultraviolent form of corporate colonialism, building a monument to a leading figure from an earlier phase of chartered companies, the slave-trading Royal Africa Company, was a powerful piece of propaganda. As in the Jim Crow-era American South, so in Bristol just a month before Rhodes’ Jameson Raid in South Africa, a statue was erected to celebrate a renewed politics of anti-black violence, by memorialising the age of slavery.

The ongoing daily presence of the Colston statue in the centre of Bristol, and the sustained inaction of authorities over a quarter of a century despite an ongoing grassroots campaign, gave way last weekend to its removal by protestors, pulled down and thrown into the harbour. Some will seek to depict this moment as destructive or iconoclastic. Others, looking at a community addressing the fact that racist monuments of colonial proto-fascism are still with us – their messages of hate and intimidation clearer than ever – compare it to the active removal of symbols of National Socialism and Communism in Germany. As Zarah Sultana MP asked in the House of Commons on Monday 8 June, “[is it] right that black Britons have to walk in the shadows of statues glorifying people who enslaved and murdered their ancestors?”

Here, the lines of British public debate about heritage and racism are being redrawn. Through the #BlackLivesMatter movement, people are using statues and museums as public spaces to re-frame how we think about anti-blackness and social justice in the twenty-first century. They are becoming places to gather, and to acknowledge the ongoing nature of the colonial past. The transformative actions that result can take many forms, including removals. These actions are operating at a new pace. Twenty years ago the Macpherson report into the killing of Stephen Lawrence showed how institutional racism could cause inaction by the authorities in the face of racist violence. Now people are asking why, after 25 years of community dialogue, the work of erasure had to be performed by protesters. In a landmark announcement, on Monday 8 June Historic England stated that they do not believe that the statue “must be reinstated”. As a city-wide dialogue about the fate of Colston begins, attention is shifting to how Bristol might next dismantle its other principal bronze monument to anti-blackness – by returning the Benin head violently looted from Nigeria in 1897, currently on display at the other end of Park Street in Bristol City Museum. This trophy of colonial war was – like the 1895 statue of Colston – displayed in order to celebrate, and thus to naturalize, the ongoing dispossession of the global south through anti-black violence. And as with removing the Colston statue, so for restitution to Africa, ‘dialogue’ has stifled action for decades.

Achille Mbembe responded to the fall of the statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town in 2015 by describing it as “a moment when new antagonisms emerge while old ones remain unresolved.” In Britain today, the #BlackLivesMatter movement is joining the dots between the unresolved antagonisms of an 1895 bronze statue of a slave trader and a bronze statue looted from West Africa in 1897. Calls for action are not about iconoclasm, but about ridding our cities of the enduring infrastructures of white supremacy, tracking and tracing a disease that attacks the ability to breathe. On the same weekend as Colston fell, many responded to the British Museum’s Black Lives Matter statement by demanding not words, but action on the restitution of artworks and human remains to Africa. As the parallel demands of the Fallism and Restitution movements grow, it is the duty of Britain’s arts and heritage sector to no longer care for and protect objects more than we care for and protect people. Yes, silence is complicity; but so is dialogue masking inaction.

Dan Hicks is Professor of Contemporary Archaeology at the University of Oxford and Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum. He is the author of The Brutish Museums, forthcoming on Pluto Press.