The Brooklyn-based artist’s work sustains a tension with its viewer, resisting your attention with its coy gestures, then telling you its most vulnerable secrets

I spoke to Win McCarthy a few moments after he’d come out of a nap in his studio, which is in Red Hook, Brooklyn, just across the highway from the neighbourhood where he was raised. He rented the space long ago, cheaply, through a connection he’d made playing local baseball as a kid. It’s an old warehouse with industrial decor and bad drywall, and “sometimes you can’t totally tell the difference between what’s the wall and what’s the work”, he tells me.

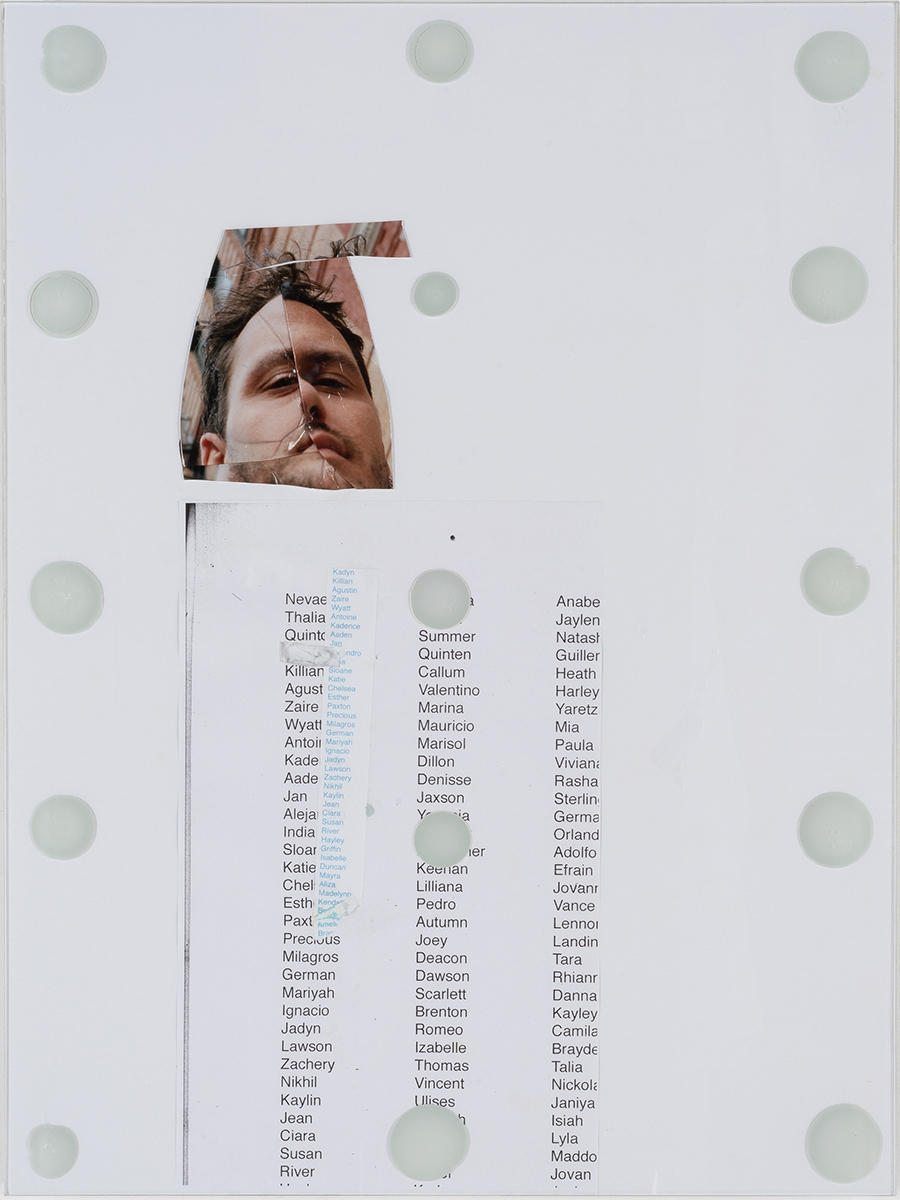

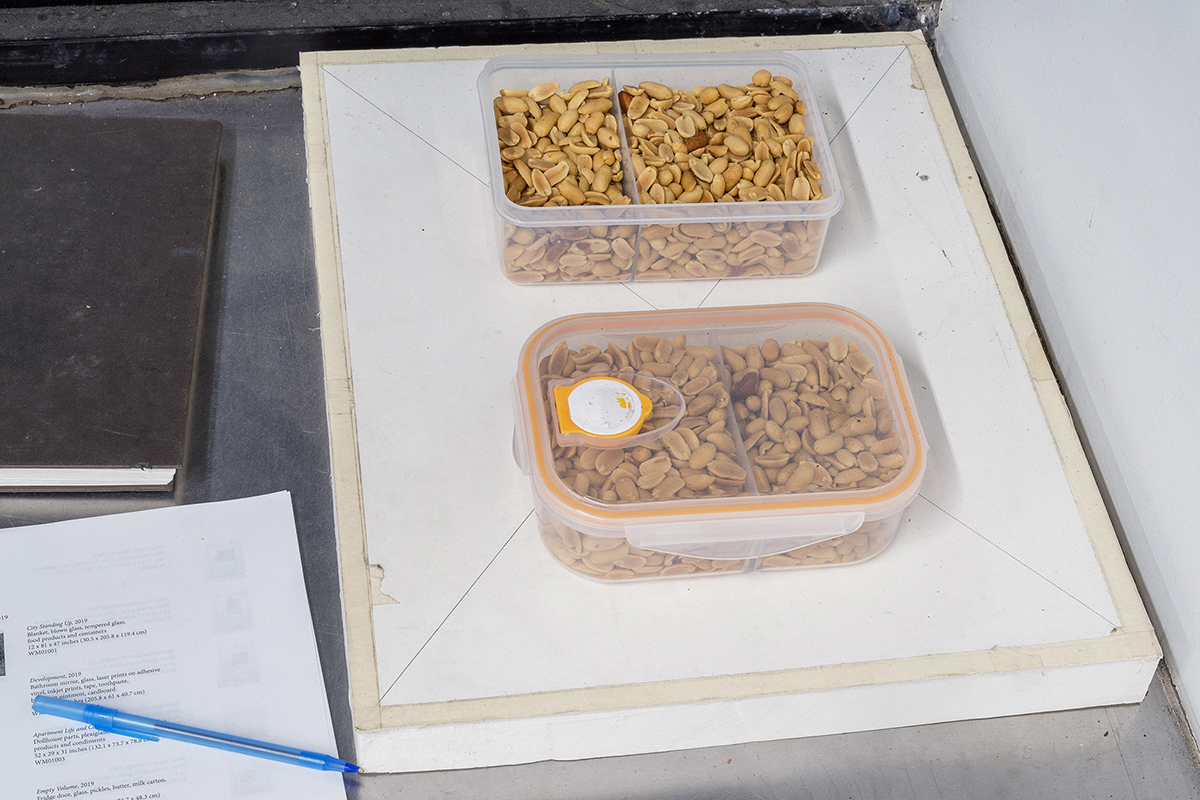

In 2019 McCarthy had a show titled Apartment Life at Svetlana, in New York’s Chinatown, depicting his experience of being shaped by the city’s living conditions and fishbowl privacy. The exhibition included well-used items from McCarthy’s home (linens, bathroom mirror, toothpaste, keys) and a refrigerator stocked with foods representing his personal diet: rice cakes, a stick of butter, a can of Coke. ‘Containers and their contents,’ as McCarthy describes the work in his press release. These contents were coated in all their natural grime and schmutz, presented with a kind of alien uncertainty, as if McCarthy were recreating an urban habitat he had never truly called home, without a trace of sentiment.

For McCarthy, a life spent in stacked boxes has developed a ripping anxiety within him, which is often the subject of the following interview. Much of his work seems to be a form of documenting this anxiety through an increasingly expanding range of media: photographs of the city, lyrical text scrawled on the work and architectural schematics that suggest confinement. His sculptural work pays particular attention to the body, with moulds of McCarthy’s head and feet, stuffed dummies and other ominous human-shaped forms. His shows take an almost novelistic approach to his autobiography, making quiet references to all the nooks of his daily experience. At the time of this interview, however, McCarthy was at a kind of fulcrum in his work, turning towards some new, not yet fully understood stage, which includes baby doll heads and his father’s old suit.

Several times throughout our conversation McCarthy requested that we stop speaking about a particular topic, and we did, for a moment; but in all of these cases he quickly resumed speaking about that very subject at length, with depth. In general he has an experimental relationship with his public profile, as he is nowhere to be found on social media, and what follows is his first published interview. His work sustains this tension with its viewer, pushing and pulling, resisting your attention with its coy gestures, then telling you its most vulnerable secrets. The more I look at his sculpture, the more I get the sense of being engaged in a subtle psychological game with its maker. Speaking to McCarthy on the phone, in the midst of the pandemic, gave this feeling a personality.

Art Is Not Net Positive

Ross Simonini Where are you?

Win McCarthy In my studio.

RS What’s it like in there?

WM It’s kinda like… pretty big, for New York actually. It’s got wood-raftered ceilings, it’s got tons of conduit on the ceiling that no longer has cable in it from ad hoc electrical jobs that have been done in the past… I’m just walking around in here, looking around. Should I keep going?

RS In an email, you told me that you wanted to read this interview in its raw state. Why? Is that related to the rawness of the work?

WM I mean, now I don’t even think raw would be the word. I thought, I would be interested to read a transcript that has all the ums, and the likes in it. Things like that. Coughs, dogs barking. I think it comes from the experience of being an artist always being both narcissistic and humiliating. Um. And recognising that you’ll have to suffer to enjoy both of those things. And from early on, I kind of decided that there would have to be a certain amount of self-scrutiny in it, self-ridicule, for it to uh, for it to work for me. I don’t know if that always comes through in the work per se, but uh, somehow doing the interview where it’s just a transcript, you know, something that isn’t too cleaned up or self-serving… we don’t know each other, so we don’t know what our rapport is going to be like, what the exchange is like, but I think it might be nice that, if this is an awkward conversation, that it can just be that.

RS Embrace the awkwardness.

WM And I think it fits with the work too. Like you said.

RS So this idea you were mentioning, about interviews being narcissistic and humiliating. Is this how you feel about exhibiting work too?

WM Yeah, I do always feel that way.

RS Do you get that classic, postshow feeling of letdown?

WM I actually don’t really. I get more of a feeling of disassociation, where I look at the work, and even though it was made with a certain amount of deliberation, and intention, I somehow have no memory of how it happened. Almost as if it happened to me rather than was something I willed into existence. Like it’s… all the agency disappears. But I guess that’s because you can’t take it back.

RS Is the embarrassment ever so bad that you consider not showing?

WM Oh no, I like it. I enjoy it actually. I think it’s like, it’s a paradoxical thing, because you have to reveal yourself to discover anything real about yourself. So it’s just a part of the process.

RS What’s your relationship to your body? Do you have a lot of body awareness?

WM Hmm, no? I think. Um, I guess, no, not really. I kind of – this is a hard question. I guess I should just talk about the work, rather than myself.

RS Well, you can see why I asked that, right? It’s in the work.

WM Yeah, I feel aware of both – mind and body – but I have a difficult time achieving any sense of unity. It’s a mind–body problem. It’s the difference between seeing and describing, kind of… I mean, I know you said body. But somehow I’m talking about mind, which never feels very grounded. A big theme of the work has been having to live in both – the physical and the intellectual – which I think of too as the world of anxiety. Um. And then trying to reconcile the two. A lot of the work thinks of the body as a shelf, as a storage space. But I think I’ve probably overvalued my neurotic qualities, and sort of subjugated the body into being a container, into this thing that has to carry around a confused and overburdened mind. Does that make any sense?

RS Sure, and it does make sense looking at the work, which is mostly heads. And when there are bodies, they are made of tiny sticks, or have no legs, or are just underdeveloped.

WM God, I’m actually more anxious about this whole process than I expected to be.

RS How much is anxiety a driving force in your life?

WM I think it is. I think it definitely is.

RS I mean, anxiety is one of these words that is so overused it’s hard to know what people even mean by it. What do you mean?

WM Well, I’m interested in the physical manifestations of it. I mean I think it’s really cool that it’s not a physically tangible thing, but it has such a huge impact on how things happen. And for me, I have been thinking a lot recently about how much time I spend trying not to think about the things that set off the anxiety, but those things tend to be the big existential questions, which is complicated because that’s pretty much precisely what art tends to be about. So in a strange way I’ve always felt I have to keep my work in the periphery of my mind. Like not look directly at it. Um. And there is a fearfulness. That becomes something you manage.

RS I think the tricky part is how much you identify with your anxiety…

WM Yeah, I mean, totally. I think for a long time I thought, and you know my work is pretty focused on identity as well, and for a long time I really thought anxiety and depression were who I was. That was what was unique about me, um, but my idea about that is changing now.

RS So that’s no longer the subject?

WM No, not the thing itself, um, I think there’ll always be a baseline. My studio is full of baby dolls now. Baby dolls that are wearing, like, suit jackets, and shirts, and ties. There are lots of shoeboxes in here now too. So now there are baby dolls in shoeboxes. I was thinking about shoebox apartments, so I thought I could just stack them up and they could be apartment buildings made of shoeboxes.

RS Do you think about where you’re headed as an artist?

WM I guess I don’t know what I want, I guess I don’t know how I want all this to go… what’s the best-case scenario? Not to sound cynical, but this is a really fraught thing. It took me a long time to realise that art wasn’t net-good. And I mean that politically, socially, personally, I mean, obviously, financially. You know, for a long time I thought it was net-positive. And now I cling to the idea that art can be good (anything other than bad), despite everything.

RS Where did that understanding come from? Was it an attrition of not-goodness?

WM Yeah, I mean, and then just a sense of the hubris of it, of pretence. I remember having early experiences in museums where, where the wall text next to the work requires you to really extend the benefit of the doubt to accept the way these things are talked about, and mythologised and made a part of history. What they ostensibly mean. And there was a period where I was writing on my work a lot, and it came from that.

I thought I’d just write what the work was, on the work. Really being a bad sport. There was something pretty cynical about that, I think.

It Almost Can’t Be True

RS Do you have another job?

WM I do.

RS Is it worth discussing?

WM Hmm. I’m not sure if I want to talk about it.

RS OK. You don’t have to say what it is…

WM OK, I’ve actually always had a job, except for a brief period where I quit to do this show at Off Vendome in the city. I quit my job before the show, because, you know, I thought it was a big deal, and then I made like $14,000 from it and literally never thought I was going to work again. And then of course I was completely broke a few months later and started doing odd jobs and then kind of miraculously landed a really reliable, flexible, consistent job. Which has been great. It’s been nice to have that. The brief period where I was, you know, a professional artist was like, extremely unproductive. I was just so guilty about coming to the studio and lying on the couch all day. It’s never been something I can just show up to, clock in to. There isn’t enough busywork. So I work. It’s really good for me to have to show up for somebody else. I’m really not good at doing that for myself.

RS How do you like to engage with art?

WM Yeah, I mean, I like to read about it. I actually really like to look at pictures of it on my phone. Weirdly. My friend has a gallery in Queens called Gandt. Really been enjoying going there.

RS Do you read about art?

WM I like reading about it anecdotally. I mean, I read this Walter Benjamin biography at the beginning of quarantine. There’s a story about him going to stay with Brecht in Denmark, and apparently he really loved this whole street of tattoo shops in Copenhagen, and he bought a sheet of flash off of a tattoo artist, and this is probably late 1930s, early 40s, during his exile, and it was on vellum, or like transparency paper, and apparently he kept it with him for his whole life, and he was itinerant for all of those years, moving all over Europe, and this sheet of tattoos was with him the whole time. I like reading about it anecdotally like that. Historical, personal accounts of art. Running into art; recognising art.

RS As you said, writing is everywhere in your work – is this something that happens as regularly as making the art?

WM Just as infrequently, yeah, but sort of equal. In the beginning, I felt like I made work really intuitively, and that frightened me. Because

my whole understanding of art was as an analytical process. So it was always a retroactive way of giving myself permission to make something. You realise that you have to make it as an intuitive person, and you look at it as an analytical one, and the writing was a way to reconcile those things. Why I have to make these things distinct is another question. So the writing would happen a lot, and I always wrote in sort of a poetic voice, because that seemed instructive for the works. I wanted them to be more of the world of poetry. I actually went into undergrad thinking I was going to study poetry. Things went a different direction.

RS What poetry were you reading in college?

WM The only poem that I can think of that I really loved in college was this poem called ‘Index’ by Paul Violi. And it’s written, or structured, as an index for a biography of an artist, actually. A painter in the seventeenth century, I think. He goes crazy at some point, he’s arrested at some point. There’s one section called ‘Arrest and Bewilderment’, and then he’s a poet too, so little pieces of verse are in the index too. And at the very end, on his deathbed, he writes, ‘I think I am about to snow’. With poetry, I love that you can see the whole thing all at once, which I guess is funny because I’m admitting I don’t read poems generally that are longer than a page. But yeah, I love that they have a shape. You can look at them.

Discovering the Medium

RS You said you work ‘infrequently’. Do you just casually grab moments throughout your life to write and make art?

WM Yeah, I mean, I don’t have a schedule. I probably should. But no, when I write I write a whole poem. It may end up in fragments in the work in some way later. I write with the understanding that one line might get pulled out and blown up. And there is something in the work, we were talking about bodies earlier, thinking about body as a group of constituent parts – like, hands fingers toes, knees eyes nose whatever – that you think of a sentence the same way – grammar, parts of speech, you know – so I’ve always liked using these organising structures – be it the inside of a fridge, or an architectural plan.

RS The show Apartment Life made me think that you feel oppressed by the buildings around you. Does it feel that way?

WM Yeah.

RS There’s this kind of despair from that mode of living. Is that…

WM Yeah, it’s a kind of fatigue, um, of feeling like a big part of life is contorting yourself around things that you can’t change. Always adapting, never having firm footing or a totality of understanding about, like, pretty much everything – including who you are in all of it. So yeah, there is a despair in that, there is a futility in that, but like, that’s kinda what it’s all about, right? [laughs] The struggle against futility?

RS Do you think of art as a form of communication of these feelings?

WM I think so? I’m trying to think of the art I like… I love the unspeakable thing, the feeling of a chill. You know you get that with a [Rosemarie] Trockel piece, where it almost can’t be true.

RS Who else does that for you?

WM Umm, Lutz Bacher. There’s this book she wrote called Shit for Brains. She wrote it like, in a fury right after her husband died. And it’s supposed to be a novel but it’s really all sorts of different things and types of writing. But she wrote it on 8 1⁄2 × 11 paper, just like with a few words on each page. Then she’d flip to the next page and it is so immediate and raw you could say, but she gets to this place in the middle that I always think about and it’s just one page, and you know she’s writing in big letters barely with punctuation in it, and she just writes, ‘I wish I had known I could write this way all along’. And then flips to the next page and it’s back to, um, and you have this chill that you’ve witnessed her inside the medium, discovering the medium, and then it goes from a moment of her intuiting it to recognition that this thing has happened to her and it’s new and strange – maybe like the death of her husband. I always feel like it’s the fulcrum of that book.

RS With both of those artists, I think that chill comes from individual works but also from their whole body of work, taken together, how every work relates to each other…

WM Yeah.

RS …how each object almost rejects the previous one. Is that how you see your work?

WM It’s a cumulative process, adding to the pile, and you feel the resonance of all those things behind you. I definitely try to work that way, and it’s cool, back to the identity thing, you work so hard to grow and to change – a lot of the work is about the fatigue of that very thing too – and you think you change, but it’s frustrating when you realise you are right back asking the same questions. You switch mediums, you pick a different starting point, and it’s that same big glaring central question.