The artist’s show at Gammel Strand, Copenhagen explores historical memory, and the slipperiness of nationhood and belonging

Things to Come, featuring works from 2008 to 2023, opens with a wall of screens showing a single image: the seven-minute Zukunftsbewältigung (Overcoming the Future) (2023), whose title inverts the term Vergangenheitsbewältigung, German for coming to terms with the past. Three figures dance in slow motion on a patch of grass in the dead of night, backs to each other, distant light illuminating their diaphanous white gowns and their horse, ram and donkey masks. A distorted choral chant echoes as they rise and slump, as if Bartana is choreographing some ritual – a shaking off of the past and a readying for the future.

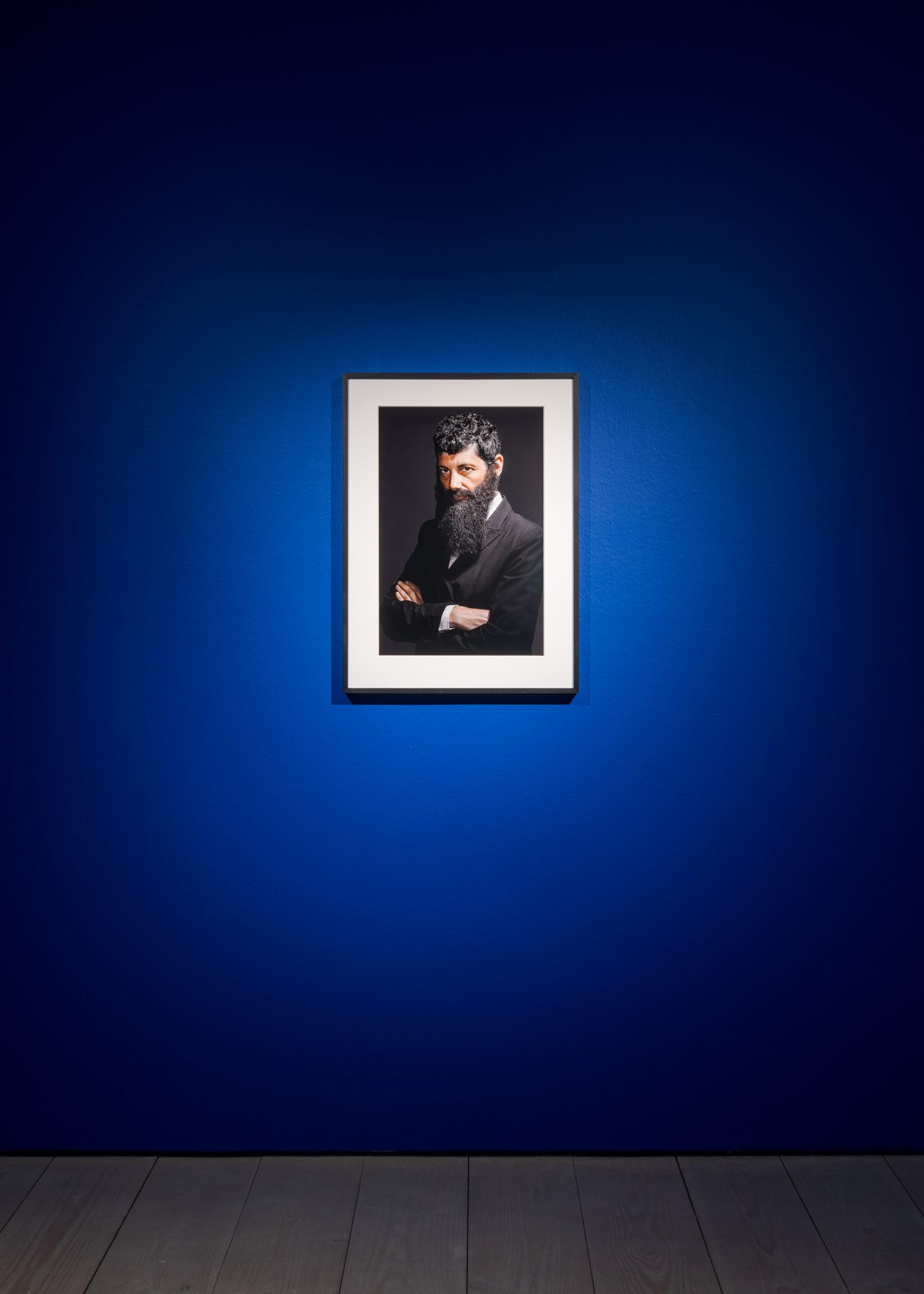

Born in Israel, Bartana studied art in Germany and since the mid-2000s has lived between Berlin and Amsterdam. Her exploration of historical memory, and the slipperiness of nationhood and belonging, is inextricable from her background. The Missing Negatives of the Sonnenfeld Collection (2008) recreates photos by Herbert Sonnenfeld, who documented the influx of Jews to Palestine from the early 1930s onward. These images of ruddy young Zionists tilling the earth to establish the nation of Israel became a powerful part of its imagination; Bartana recast Sonnenfeld’s subjects with contemporary Palestinians and Mizrahim (Jews from Muslim-majority countries). She revisits this body-replacement tactic elsewhere, a trickster inhabiting others, reminding us that the narratives and iconography of history are always being rewritten and reshaped: Stalag (2014/15) sees her dressed up as an SS officer holding a film camera back at us, threatening while documenting. In Herzl (2015) she dresses up as (a quite handsome) Theodor Herzl, founder of modern Zionism, whose specious slogan ‘A land without a people for a people without a land’ anticipated the violence at the heart of present-day Israel and Palestine.

Two Minutes to Midnight (2021) splices footage from Bartana’s 2019 live performance Bury Our Weapons, Not Our Bodies!, which took place in Philadelphia during the Black Lives Matter protests, with long outtakes from the 120-minute performance What if Women Ruled the World? (2017/18). Shots of protesters carrying rifles to a cemetery, where they are buried in a ‘call to end all violence’, are intercut with a roundtable of women in a war room discussing a fictionalised imminent nuclear war with a country led by ‘President Twittler’. Referencing Dr. Strangelove (1964), Bartana swaps Stanley Kubrick’s alpha males for an all-female cast of actors and specialists from the fields of culture, diplomacy, security and international law, who – despite hopes that a feminist world power might shift power politics away from violence – all eventually seem to agree that we should neither de-escalate nor disarm. It’s an awkwardly constructed narrative, and some ham-fisted gags feel simplistic (the woman president smokes cigars, phallic cacti and fruit sit about the roundtable, buff shirtless men serve refreshments) but Two Minutes to Midnight ably documents the bad-vibe panoptic claustrophobia of the Trump/COVID-19 years, distancing the latter while suggesting how quickly they might return.

In the three-channel Malka Germania (2021) – Hebrew for ‘Queen Germania’ – a slim, blonde, androgynously beautiful figure wanders contemporary Berlin, as the Israel Defense Forces conquer the German capital and replace German street signs with Hebrew ones. ‘Malka’ rides through the Brandenburg Gate on a donkey; aerial shots track over the Berlin Victory Column to moody synth chords. Out in Strandbad Wannsee, she joins sunbathers gobsmacked by (a CGI rendering of) Nazi architect Albert Speer’s planned Volkshalle, rising from the lake. She wanders along a rail track out into a forest; on another screen, men, women and children carrying bags and suitcases tramp along the rails to the forest, where women in translucent gowns dance in the mist, recalling the work of Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. These imaginings around European Jewish experience, nationhood and return, and fascist imagery are a sort of sequel to Bartana’s equally cinematic and slickly produced … And Europe Will be Stunned (2007–11, not on show), which imagined Jews returning to Poland – their ‘ancestral homeland’ – and building a fortified kibbutz on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto.

It’s here that Bartana seems most at home, using cinematic language to create grandiose yet slippery scenes that undermine inherited historical symbols and narratives of nationhood and identity. This work also contains the show’s most stunning images: seen in slow motion, domestic objects are thrown out of Berlin apartment windows. A ceramic beer mug smashes on cobblestones; plates, kitchenware, clothes, furniture follow. This image of discarding is emotionally charged and painfully ironic in a way that encapsulates Bartana’s concerns. See these events now and they suggest a wish to get rid of old baggage – a simple yet powerful dream of emancipation and looking to the future. But see them ‘then’: it’s Waffen-SS raiding Jewish homes, throwing their belongings out the windows, the lives of people who thought they were German, believed they belonged to their land and nation; an illusion that ended in the death camps. That’s the core of Bartana’s work: the painful dissonance of trying to shake off the past only to find the present repeating history, and blocking a path to the future.

Things to Come at Gammel Strand, Copenhagen, 2 February–20 May