In a new show at Night Gallery, the artist offers highly emotional, disjointed excerpts of lives that evade understanding

Yooyun Yang’s paintings seem otherworldly: an emergency exit sign becomes an alien lifeform, a ray of light bisects a woman’s face. Their sources, though, remain close to home: the artist transforms photographs – some taken on her phone by accident, some from popular Korean news programmes, some of friends in Seoul – into visceral, uncanny visions. These are paintings enabled by the near-terrifying ease of technology; descendants of a lineage that began with exhaustive studio setups and long exposures, phone cameras might now, in a fluke, take a picture of the back of a user’s hand or the curve of her elbow. In Stranger, the South Korean artist’s solo debut in the United States, Yang composes a haunting view of a mediated landscape defined by the coexistence of intimacy and estrangement.

Painted on jangji, a Korean mulberry-bark paper, Yang’s artwork creates images of present-day urban environments using ancient technique. In Midnight (all works 2023) a woman’s eye dissolves into a stripe of artificial red light, each brushstroke melting into a background striated by the paper’s veiny fibres. Yang uses the highly absorptive material to disorienting effect: though each painting often features markers of contemporary life – many include bright flashbulbs and bluish glows reminiscent of computer screens – the artworks themselves are eerily matt. Modernity’s sheen becomes muted and bodily on jangji’s skinlike surface; in Butterfly an emergency exit sign emits a moody indigo halo, the shape and feel of which indeed resemble a butterfly’s open wings. Under Yang’s hand, the boundaries between human life and digital artifice are porous, each overlaid on the next.

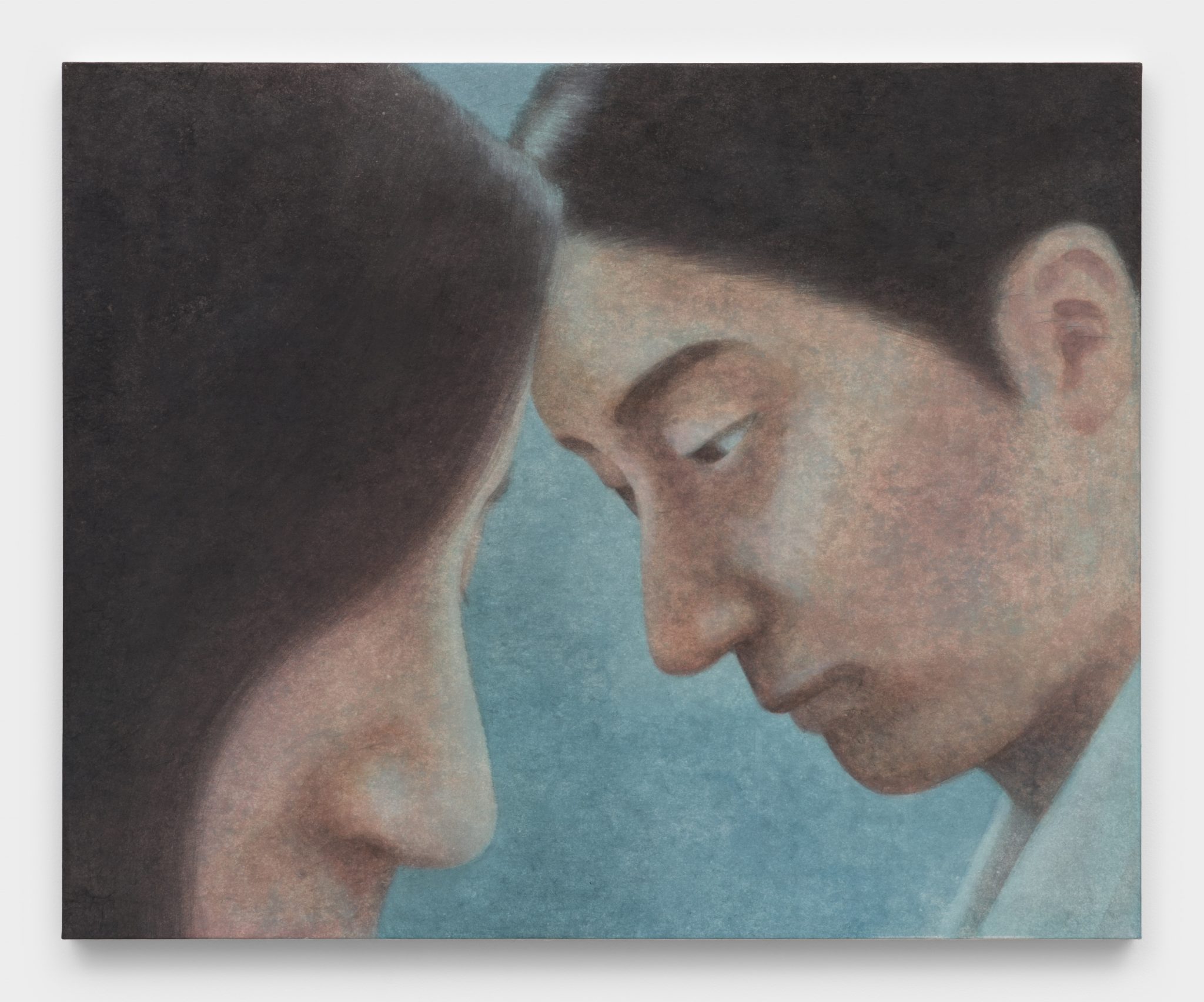

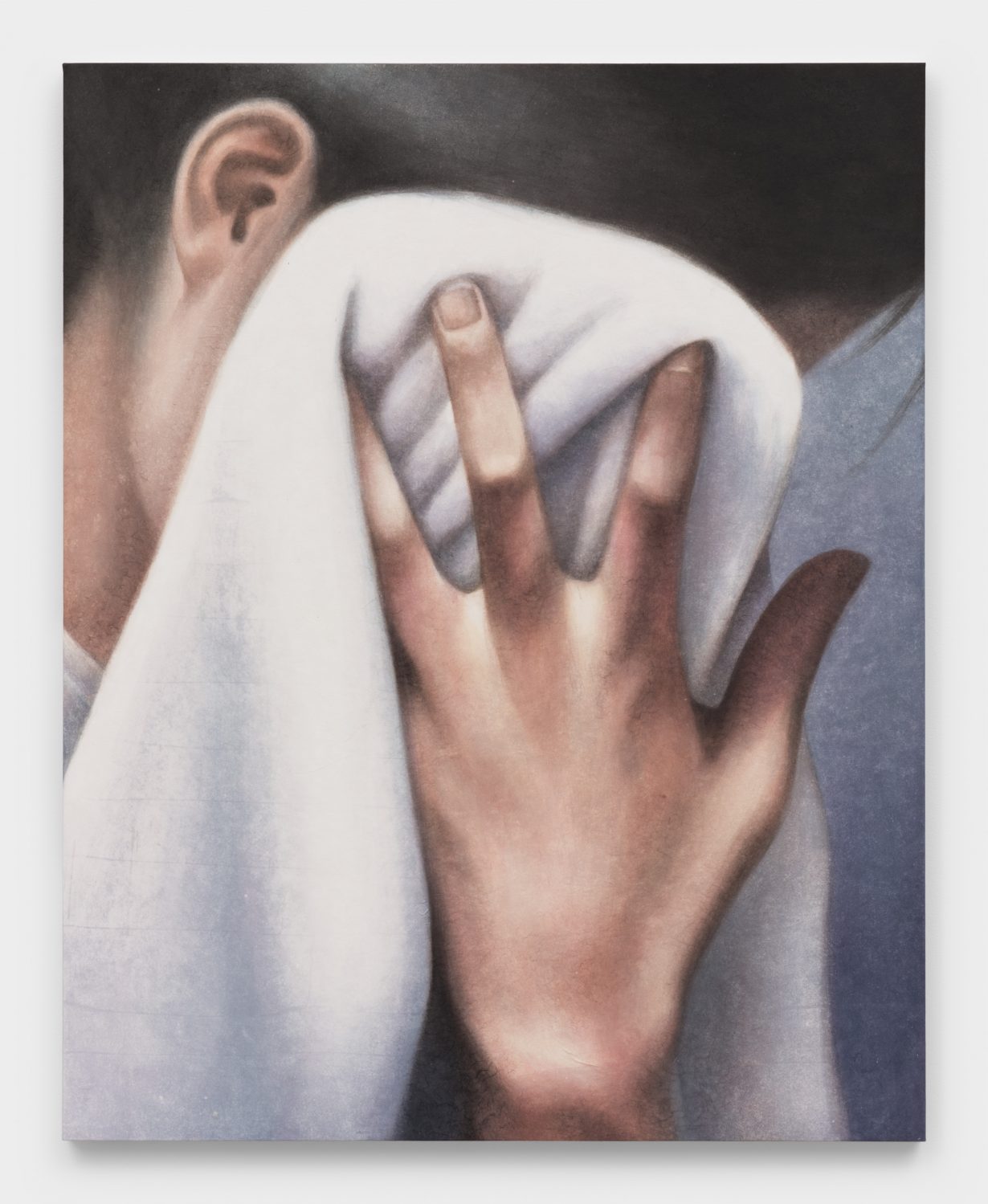

Yang’s compositions morph photographic snapshots into scenes of intense, confusing disconnection. The artist paints closely cropped versions of her original images to emphasise their unfamiliarity: in A Deflected Gaze a man stares past a woman who closes her eyes; Stranger shows a hand covering a face with a folded white cloth. Obscuring access to her subjects’ stories, Yang instead offers highly emotional, disjointed excerpts that evade understanding. Ring features an outstretched hand with a flash bouncing off a finger, but both the light’s source and its reflection resist logic: there is no such ring apparent on the hand that would produce a sharp glare, and the painting does not reveal a flashbulb. In Child a dark shadow shields the infant’s face from view entirely, its origin concealed to similarly unnerving results. Yang renders everyday sights through a discomfiting gaze, contorting fragmented media into unsettling dramas.

Jangji has been used for centuries by groundbreaking Korean printmakers: both the world’s oldest known woodblock print and the oldest known metal-type print were produced on the fibrous paper in provinces near Yang’s Seoul hometown. The material’s organic texture renders Yang’s alienated, cosmopolitan scenes in a uniquely tactile way, capturing the odd intimacy of contemporary experiences with technology. These works evoke the surreal familiarity of late-night doomscrolls and early commutes, of solitary walks under a billboard’s light. You should see Yang’s paintings in person – but viewing them online might be more aligned with their ethos.

Stranger at Night Gallery, Los Angeles, through 9 September