Julie Chun navigates her way through art and cultural histories

Entering this exhibition of paintings by Zhang Yunyao is a confounding experience. The Shanghai-based artist offers viewers a visual assault of classical Greek and Roman forms, which have little context in his homeland – particularly for general audiences who may not be aware that such forms provided a model for socialist-realism productions that dominated Chinese art during the period of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). As you move from one enormous panel to the next, Zhang’s figures materialise in hyperrealist glory, hand-rendered not in oil on canvas but rather graphite on felt, an unconventional medium that has engrossed the artist since 2011 for its challenging tendency to smudge and soil.

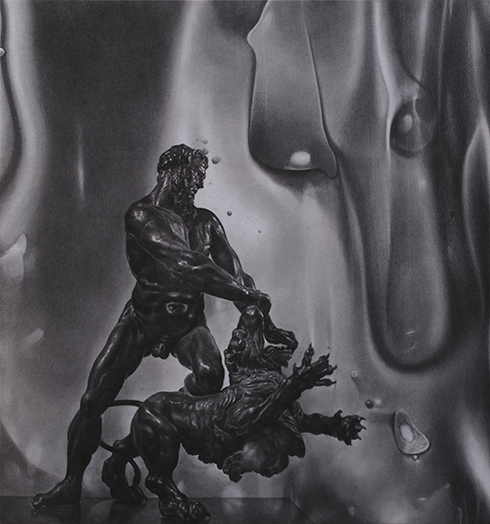

An overwhelming sense of disquietude pervades each of the 16 canvases hung in the main gallery, since very few, if any, of Zhang’s depictions can be easily traced to exact sculptural prototypes. He has bastardised his portrayals of eminent gods, goddesses and emperors with aggressive marks of overdrawing and fractured compositions, as if his painted sculptures are at the point of implosion. The valiant Perseus holding aloft the head of Medusa in Study in Figures (avidatia) (2017) is himself decapitated and fragmented in layers in Zhang’s interpretation of the iconic form. The fierce gesture of Heracles as he fights a lion with his bare hands in Release (2018) and of men abducting a resisting Sabine woman in Study in Figures (2019) signify a declaration of penultimate perfection in their nude naturalism, as if chiselled like marble statues. Zhang’s use of archetypes from Western antiquity exemplifies the ways in which ideal paradigms can be appropriated as symbols of authority as evinced by the passage of forms since the civilisation of the Greeks, the Romans and the Renaissance, and their revival for neoclassical creation of a nation by the United States’ forefathers as well as by the Soviet and Chinese Communist regimes. While embodying the ethos of classical ideals, Zhang’s paintings also direct our gaze to the transgressive nature of subjugation that often accompanies acts of domination.

Most poignantly, as revealed in Release, the masculine virility of Heracles, for example, stands against a background of draped flaccid forms. Notwithstanding acts of aggression evinced through the deployment of terror or force, Zhang seems to suggest that even the most Herculean power cannot sustain its erection.

Zhang Yunyao, Palace of Extasy at Qiao Space, Shanghai 10 October – 12 January 2020

From the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia